(Editor’s note: Welcome to the second in a new series on price theory issues. Professor Brian Cutsinger. This month’s questions are reproduced below. you can too View original post From the beginning of this month. You can also see Click here for the solution to last month’s problem. )

question:

Crude oil is commonly used to make gasoline, heating oil, jet fuel, lubricants, asphalt and many other products, according to the Energy Information Administration. Assume that the proliferation of electric vehicles (EVs) reduces the demand for gasoline but does not affect the demand for other products co-supplied with oil. How will the proliferation of EVs affect the prices of these other products?

answer:

The idea for this question was inspired by Deirdre McCloskey’s excellent Theory of Price text. Applied theory of prices. I like this question because it highlights the interconnectedness of markets and how powerful the supply and demand framework is.

Before we get to the answer, let’s review two important ideas.

The first idea is that a demand curve can be read as a schedule showing the maximum quantity a consumer is willing to buy at a particular price, or a demand curve can be read as a schedule showing the maximum quantity a consumer is willing to buy for a particular good. It can be read as a schedule showing the best price. A quantity that reflects the marginal values of different quantities. For example, if the price of oil is $50 per barrel and the quantity of oil demanded at this price is 100 barrels, the marginal value of the 100th barrel is $50.

The second idea is that when a good jointly supplies multiple products, such as oil, the demand curve for that good reflects the vertical sum of the demand curves for those products. For example, suppose oil co-supplies only gasoline and jet fuel at a fixed rate. Suppose that the marginal value of gasoline produced from 100 barrels of oil is $30, and the marginal value of jet fuel produced from the same barrel is $20. In this case, the maximum price people are willing to pay for the 100th barrel is $30 + $20 = $50.

With these two ideas in mind, let’s answer the question. To be clear, my answer assumes that both suppliers and demanders in the oil market are price makers and that the oil supply curve is upward sloping. Other alternatives to these baseline assumptions can be considered, but for our purposes these assumptions are sufficient.

drop in gasoline request It reduces both the price of oil and the amount of oil supplied to the market. As a result, the supply of other distillates produced from petroleum should also decline as suppliers are producing fewer barrels of oil. Therefore, the prices of these distillates must increase in order for the quantity demanded of these distillates to equal the currently decreasing quantity supplied.

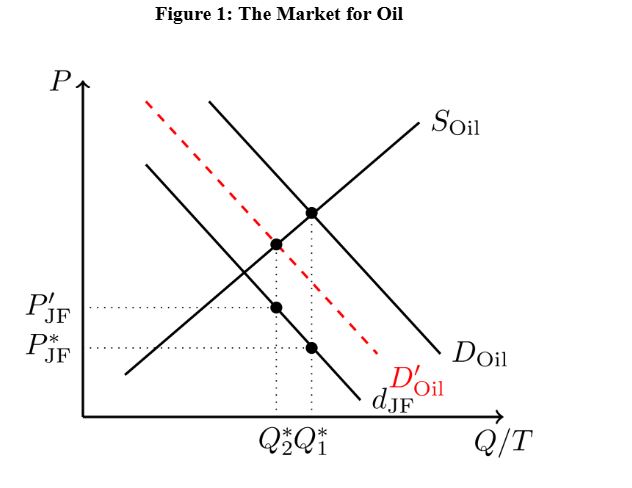

Figure 1 illustrates this scenario graphically. For simplicity, this figure includes demand for only two distillates: gasoline and jet fuel. The demand curve D_Oil reflects the total demand for oil. That is, it consists of the demand for oil as gasoline and the demand for oil as jet fuel. The demand curve d_JF reflects the demand for oil as jet fuel. The vertical distance between the demand for oil as jet fuel, d_JF, and the total demand for oil, D_Oil, represents the demand for oil as gasoline.

Initially, Q*_1 barrels of oil are available. For this quantity, the price of oil as jet fuel is P*_JF. When the demand for gasoline falls, the total demand for oil falls. This is illustrated by the demand curve D’_Oil in Figure 1. At the new price, suppliers are only willing to supply Q*_2 barrels of oil, so the price of jet fuel must rise to P’_JF.

Brian Cutsinger is an assistant professor of economics at Florida Atlantic University’s School of Business and a Phil Smith Fellow at the Phil Smith Center for Free Enterprise. He is also a Fellow of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Sound Money Project and a member of the editorial board of the journal Public Choice.