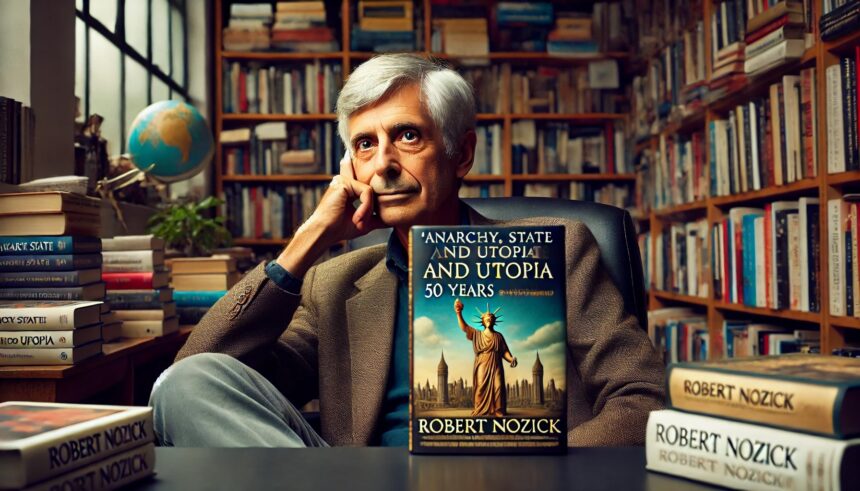

Checking in fifty years later, one observes that Nozick has had great influence, even though philosophers remain divided on the ideas he put forth. Philosophers who work in the classical liberal tradition are more plentiful now compared to when Nozick wrote, and they are taken a little more seriously. While there are non-Nozickian approaches to arguing for liberalism, the success of Nozick’s work is one reason this variety of approaches has grown and developed. His arguments may have had less traction than some liberals might have hoped—Marxism and Rawlsianism are still the predominant approaches, and there are a few more academic anarchists than there used to be (another theory targeted by Anarchy, State, and Utopia), but it’s fair to say that the book itself holds up extremely well and is rightly regarded as a major contribution to political philosophy. It also supports liberal economists’ emphases on rights of property, contract, and market entry. Let’s have a look at some of the ways in which it continues to be a significant work.

The very first sentence of Anarchy, State, and Utopia says, “Individuals have rights, and there are things no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights).” Some of Nozick’s early critics assailed him for having merely asserted that people have rights without providing an argument, but this is plainly false. The argument is in chapter three, which makes one wonder whether these critics were quick to dismiss a book the conclusion of which contradicted their priors rather than actually looking at the argument. He specifically cautions against this on the same page, just two paragraphs down: “many persons will reject our conclusions instantly, knowing they don’t want to believe anything so apparently callous…. I know that reaction; it was mine when I first began to consider such views…. This book contains little evidence of my earlier reluctance. Instead, it contains many of the considerations and arguments….” So while in the first two chapters, he is working on a promissory note, he makes good on it in the third.

The argument for rights is based on the “fact of our separate existences.” That is not to say that we do not have connections to other people or derive some component of our self-image from the various communities we inhabit, merely that we are nevertheless distinct individuals, each with his or her own life to live. This, he argues, creates moral side-constraints on how we treat each other. There are echoes here of both John Locke and Immanuel Kant: one argument for the side-constraints is that no one could by nature have a claim to own another person, so we can’t rationally understand another person’s existence solely in terms of them being a means to anyone else’s ends. Nozick is firm on this. People are ends in themselves, existing for their own sake. He uses the example of tools: tools exist in order to help people accomplish their ends; the tools don’t have ends of their own. But people do exist and have ends of their own and are not to be regarded as tools for others’ ends. Using a person as a tool for your own ends “does not sufficiently respect and take account of the fact that he is a separate person and that his is the only life he has.” This is what it means for there to be moral side-constraints on how we treat each other. “Moral” because of course, one can treat others as mere tools, use them only to further one’s own goals with no regard to their dignity and autonomy—but it is morally wrong to do so. Nozick argues that if this doesn’t hold—if there are no constraints on how we may treat others—then there’s no morality at all. These side-constraints on how we may treat others are what rights are: if you’re morally required not to do X to me, then I have a right not to have you do X to me.

If we have rights in a moral sense, Nozick argues, that has legal implications for the political/economic order. Returning to the opening sentence: there are things no person or group may do without violating those rights. This means that many conceptions of what government is supposed to do may turn out to be logically incompatible with taking people’s rights seriously. We tend to recognize wrongful government action when it’s a different government more easily than we recognize it when it’s our own. Looking, for instance, at a theocratic society, most people in a liberal democracy will notice the lack of religious freedom and the imposition of a single set of values. When looking at a one-party state with strict control of all work and media, members of a liberal democracy will notice the lack of voter choice and the problems caused by suppressing economic and journalistic freedom. It’s much better, they surmise, that people have freedom of press and freedom of occupation, and can vote for a better candidate if they don’t like the ones in office. However, it’s sometimes harder to see the ways in which a liberal democracy can also violate rights. The easiest way is when checks on majoritarian democracy are weak or poorly understood. Then we can have majorities regulating what others might want; for example banning interracial marriage, or prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcohol. More subtly, Nozick notes, conscription (still U.S. policy in the early 1970s), wage and price controls, and taxation itself also violate rights, yet we often don’t notice this, or are taught in school that that’s just the way it is.

Nozick argues that governments cannot have a moral entitlement to do things that individual people may not do. That is, the reason the government would be wrong to murder me is exactly the reason anyone would be wrong to murder me: it violates my rights. But this extends to all sorts of things that, typically, only governments do; press people into service or otherwise deny them their liberty, appropriate their property, impose restrictions on their ability to publish a book or give a speech, impose restrictions on their ability to engage in commercial activity, and so on. This means that most conceptions of good government will be rights-violative and hence morally unjustifiable. In addition to (perhaps) more obvious things like massacring or enslaving disfavored populations, it also includes things we tend to take for granted, like restricting financial transactions and seizing “excess” property. Where Rawls argues for a system in which rights to free speech, religious freedom, voting rights, and the like are fully protected for all, but where commercial and financial activity can be restricted through regulation and taxation, Nozick argues that there’s no coherent rationale for distinguishing between the two (more on this momentarily). Where Karl Marx argues for the abolition of money and private property to ensure the equal distribution of all material resources, Nozick argues that not only would this be morally unjustifiable, it would also be unsustainable.

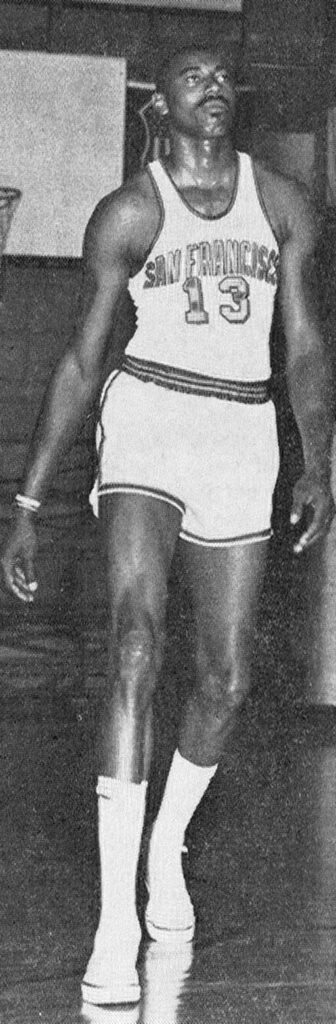

One of Nozick’s most famous thought-experiments to illustrate the inconsistencies in Rawls and Marx is the “Wilt Chamberlain argument.” Briefly, with this idea Nozick asks the reader to assume that we have in fact achieved the most just distribution of material resources, according to the reader or even Rawls or Karl Marx. Whatever that just distribution is, Nozick asks us to refer to it as D1. On D1, everyone is ex hypothesi entitled to whatever they have. Nozick then says, “suppose that Wilt Chamberlain is greatly in demand by basketball teams, being a great gate attraction…. He signs the following sort of contract with a team: In each home game, twenty-five cents from the price of each ticket of admission goes to him…. The season starts, and people cheerfully attend his team’s games…. They are excited about seeing him play; it is worth the total admission price to them. Let us suppose that in one season one million persons attend his home games, and Wilt Chamberlain winds up with $250,000, a much larger sum than the average income and larger even than anyone else has.” Nozick asks the reader whether this new distribution, call it D2, which deviates from D1, is also just. If it is not, Nozick asks, why not? After all, each person was entitled to spend that 25 cents as they pleased, and no one was coerced or exploited by Chamberlain’s contract, but the net result is an increase in wealth inequality that “upsets the pattern.” “There is no question about whether each of the people was entitled to the control over the resources they held in D1; because that was the distribution (your favorite) that (for the purposes of argument) we assumed was acceptable. Each of these persons chose to give twenty-five cents of their money to Chamberlain…. If D1 was a just distribution, and people voluntarily moved from it to D2,… isn’t D2 also just?” If we’re to maintain the pattern and keep D1, Nozick concludes, it would require forbidding people like Chamberlain from entering into favorable contracts, or forbidding people from spending their money in accordance with their own choices, or both. Since in the real world, the Wilt Chamberlain situation plays out in countless ways every day, that kind of planned distribution of resources requires constant interference with people’s freedom to choose what to do with their lives.

“If we are to take people’s rights as morally important, we will not be able to justify the multitude of restrictions on transactions that are required not only by socialism but also by the progressive-taxation-based regulatory-and-redistributionist state.”

The Wilt Chamberlain thought experiment is meant to show that not only is a completely egalitarian distribution of material resources unsustainable without massive rights-violations, so is any sort of redistributive plan. The under-appreciated significance of this is that the distinction Rawls makes between “political rights” and “economic rights” is not really a valid distinction. My freedom to choose doesn’t amount to much if I am not free to engage in transactions that give material reality to my choices. If we are to take people’s rights as morally important, we will not be able to justify the multitude of restrictions on transactions that are required not only by socialism but also by the progressive-taxation-based regulatory-and-redistributionist state. In addition to the morally objectionable rights violations these entail, Nozick might also have mentioned the further problem that these restrictions will be made through a political process, which necessarily means influence-peddling and cronyism in the selection of which transactions are to be restricted.

In assessing the continuing relevance of Anarchy, State, and Utopia fifty years on, it is also noteworthy that Nozick devotes a considerable amount of space to exploring the reality of human diversity, and to demonstrating the relevance of this for political and economic theory. Nozick notes that any conception of “the good society” will either be very minimal, or else it will exclude some people’s values and preferences while privileging others. People form associations voluntarily when there’s mutual benefit to doing so. Sometimes this benefit is as simple as facilitating the division of labor, but other times it is based on a more comprehensive set of shared values. So, left to their own devices, we can imagine people forming larger, cosmopolitan, commercial communities and also smaller, homogenous, belief-based communities. In Manhattan, for instance, people of varied beliefs and ethnicities live together because of financial or artistic benefits, while just a few hours away, in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, the Amish live in a more homogenous society where everyone shares a common religious faith and other values. Nozick’s point is that there’s no universal and objective sense in which one of these is “good” and the other “bad”—rather, each is good for some people and bad for other people. As long as people are free to form the communities they want, and no one is forced either to join or to remain, any number of communities are possible, and consistent with respect for people’s rights and autonomy. So the “minimal state” Nozick defends is not, contrary to incautious critics, a laissez-faire capitalist society. The “minimal state” is a framework, which allows for laissez-faire commercial societies and also communes, for high-tech societies and Amish country, for secular societies and religious societies—provided only that people join these communities voluntarily and may exit should they change their mind.

Ironically, some of the pushback one sees regarding economic freedom is based on alleged failure of market institutions to embrace pluralism and diversity. Nozick’s argument is that just as taking rights seriously has implications favoring the minimal state, so does respect for human diversity and pluralism. Any theory of “the ideal society” that goes beyond Nozick’s framework is necessarily neglectful of this, substituting one set of values and preferences for others in a totalizing way.

Fifty years after Anarchy, State, and Utopia, the classical liberal perspective is still not the predominant one in political and economic theory, but Nozick’s insights into the nature of rights, the significance of rights, and the reality of human pluralism remain significant challenges to proponents of more heavy-handed, illiberal theories. Classical liberalism is richer for Nozick’s contributions, and he is at least partially responsible for whatever increase in numbers we have seen over the years. The book deserves its place on short-lists of important books in political philosophy, and hopefully it will continue to find readers.

Footnotes

(1) Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (Basic Books, 1974); John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Harvard University Press, 1971). I have a more detailed discussion of Nozick in The Essential Robert Nozick (Fraser Institute, 2020). See also https://www.essentialscholars.org/nozick.

(2) Anarchy, State, and Utopia, p. ix.

(3) Anarchy, State, and Utopia, p. ix.

(4) Anarchy, State, and Utopia, p. 33.

(5) Anarchy, State, and Utopia, p. 33.

(6) The contrast would be physical side-constraints; e.g., I literally cannot go back in time or be in two places at once. Those are side-constraints on how I may act about which I have no choice. But that I shouldn’t murder or enslave someone are not physical side-constraints—one can do those things but should not.

(7) Or, a denial of the reality of the uniqueness and dignity of each person. The danger of any reductio ad absurdum is that one’s interlocutor might agree with the putative absurdity, and some philosophers might reject Nozick’s account of rights, if, e.g., they thought there was no such thing as right and wrong at all. But that’s not a move Rawls can make.

(8) Philosophy note: this approach is generally regarded as deontological, referring to one’s duties or obligations. There are other approaches to deriving rights of course, chiefly consequentialist approaches, which hold that a concept of rights is beneficial because it promotes better outcomes for society (e.g., in David Hume-, arguably John Stuart Mill-), and neo-Aristotelian-approaches, on which a concept of rights is seen as protecting the possibility of self-directed action, which is a necessary component of human flourishing (e.g., in Douglas B. Rasmussen and Douglas J. Den Uyl, Norms of Liberty (Penn State Press, 2005).

(9) Wilt Chamberlain was a top basketball superstar in the early 1970s. If that reference isn’t helping, think Michael Jordan or LeBron James, or any superstar athlete, or any A-list movie star.

(10) Anarchy, State, and Utopia, p, 161.

(11) Anarchy, State, and Utopia, p. 161.

(12) For further discussion of Nozick’s argument from pluralism, see my forthcoming “Reassessing Nozick on Pluralism,” The Independent Review, Vol. 29, no. 2 (Fall 2024).