Zach Weinersmith joins EconTalk Host Russ Roberts, in his third appearance, discusses why space exploration ambitions are unrealistic and overly optimistic, the dangers of all-encompassing utopianism, and why moving to space means buying a hot tub Discuss whether it is something like this or not.

Weinersmith is a cartoonist and the author/co-author of a number of books, including: be wolf, Coming soon: 10 emerging technologies that will improve or disrupt everything, And the topic of this podcast episode is Mars Cities: Can we live in space? Should we live in space? And have we really thought this through? Weinersmith is also the author of the following books: Saturday Breakfast CerealA daily serialized manga.

The podcast revolves around understanding space settlement as an obstacle-ridden ambition. Weinersmith closes off the possibility of settlement on the moon, for example, due to lack of water, difficulty in resource extraction, and lack of atmosphere. Mars, he says, is much more promising, but it also has its own drawbacks: a six-month journey from Earth and planetary-scale dust storms. In general, humans do not have the technological capabilities to settle in space for long periods of time. Nevertheless, Weinersmith sees the literature on space settlement as biased in defense of space exploration, regardless of resource constraints and trade-offs.

We tried to take an economist’s perspective. Because more and more physicists often hear the opinion that “we can make titanium on the moon.” But we don’t talk about Earth this way. I would never say it’s okay because in my backyard the windows are made of silicone, the metal is made of aluminum, and of course the wood is made of carbon and hydrogen. But somehow it’s okay to talk about the moon this way, as if the trade-off doesn’t exist.

Space missions have always been influenced by negative trade-offs. Weiner-Smith’s example is the Apollo program, which he believes is politically unpopular, only possible once, and too expensive in terms of resources to go to the moon for a short period of time. However, the most worrying shortcoming involves the question of whether space migration is ethical given the negative effects of space on human biology, psychology, and development.

I’m going to list a lot of negative effects that space has on humans. The longest period a human has spent consecutively in space was 437 days, so all these negative effects occurred over a very short period of time. In space, muscle density definitely decreases, especially in parts of the body that are not used in space, such as the lower back. Kidney stones may form because the body excretes large amounts of calcium. This is a reaction your body experiences when you don’t use it, and it goes away with lots of exercise and strength training. Jerry Lininger was a cosmonaut aboard the Soviet Union’s large space station Mir, and he was extremely proud of the fact that he was able to walk when he emerged after a four-and-a-half month stay. Ta.

Weiner-Smith shows that the political pretense often associated with space exploration projects, contrasted with a genuine sense of scientific inquiry, reveals how little we know about how space affects pregnant women and newborns. I’m explaining. In this case, children born in space laboratories in the future will become laboratory rats. For Weinersmith, all these issues are extremely difficult and unethical, despite having little merit, to which Roberts responds, “What’s the appeal of this?”

Roberts asked Weinersmith whether he worried that his assertion that space habitation is nearly impossible ignored technical issues. innovation. After all, there are many existing technologies that were once thought impossible. like an airplaneWeiner-Smith rejects this claim, arguing that it’s more of a wish than a legitimate counterargument, and that the need for significant innovation indicates the impossibility of space habitation.

When you talk to space people, the classic example they bring up is aviation. Of course you don’t want to get caught out by that, but you have to be careful with this kind of reasoning. The comparison to aviation in a space book about awesome space stuff coming soon was very telling, in that it was done in the ’50s…The degree to which a particular scenario requires extraordinary development says something about the nature of that scenario. If you need 100 butlers per person to get to Mars, that’s a Star Trek fantasy, not a libertarian frontier fantasy.

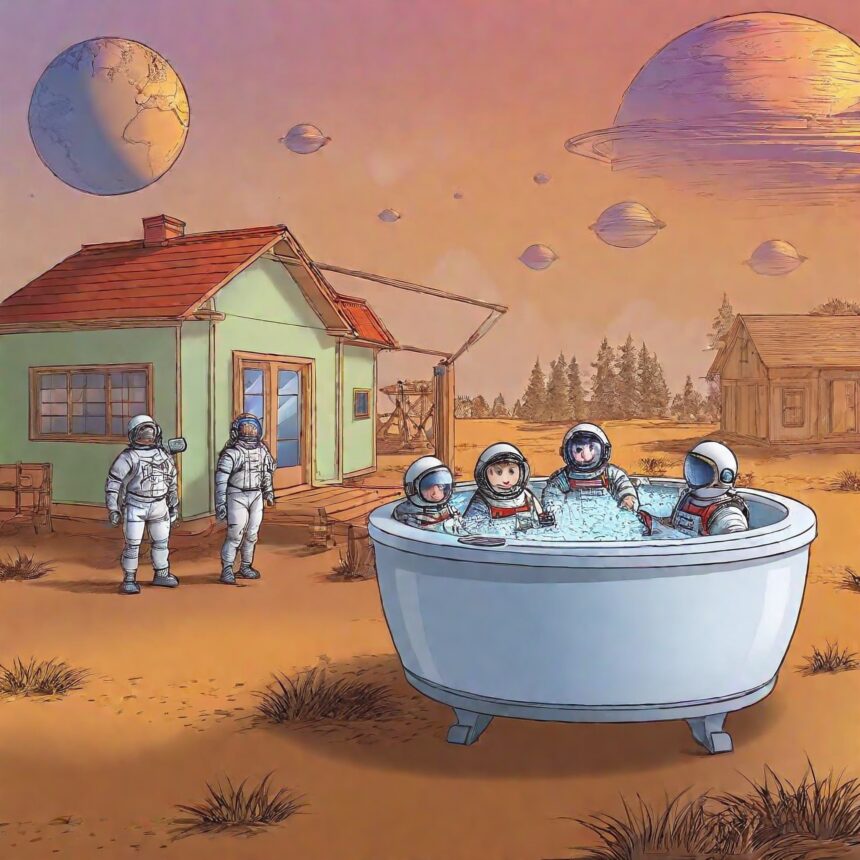

As SpaceX has shown, space travel can be privatized. Should a lack of payment technology prevent a company from attempting a mission to space? Weinersmith calls this the hot tub debate, because space travel can be as private as the decision to buy a hot tub. But Weinersmith disagrees. He believes that space travel poses risks to humanity that should be vetoed by third parties.

You can imagine a whole spectrum, from buying a hot tub, where you basically have no right to say no to a third party, to buying nuclear weapons, where basically everyone should be able to say no. The question is, where does space habitation fall on that axis? You might ask, why isn’t it a purely aesthetic choice? Now imagine, as some people have proposed, placing a million tons of metal about 70 miles high in orbit. I think most people feel that someone should have a say in whether or not they are allowed to do that, because it creates a huge danger, not different from detonating a nuclear weapon. Our ultimate conclusion is that the hot tub argument is clearly inadequate. It is not a simple individual choice. Even if you imagine things like fusion propulsion, a world in which private citizens can place large amounts of high-velocity metal in space is a world in which humanity is at risk. It seems to me that some kind of regulatory framework is necessary.

While much of the podcast is spent discussing why cities on Mars or the Moon are ill-conceived fantasies, Weinersmith acknowledges that the will to expand human civilization into space is an understandable application of the human explorer mindset. He praises the questions posed by space advocates as fascinating and intriguing. Weinersmith isn’t telling his audience to stop exploring, innovating, and asking questions. Instead, he asks us to slow down the utopianism surrounding space exploration and recognize the high barriers and serious risks.

The other thing that I would like you to reconsider is that that particular fantasy tends to be more liberal in the American sense, or conservative frontier fantasy. But I’ve seen this as a left-wing fantasy. For example, avoiding capitalism when going to space. When the universe allows any utopia to exist, you should think again.

Roberts states consistently throughout the episode that he finds Weinersmith’s ideas somewhat depressing. But I don’t think so. Weinersmith’s book acknowledges that there are no panaceas, and that attempts to create one could end up with disastrous results. Given the sometimes depressing state of the world, it’s tempting to be able to start anew. Weinersmith asks viewers to consider the costs of doing so. In my opinion, those costs start with climate change. Space exploration is a workaround, not a true solution, as is often the case with utopian ambitions. For example, Socialism Utopianism is not the answer to economic inequality, social exclusion, and worker abuse. It is an imaginary rocket to a world where the flaws of capitalism do not exist, ignoring the ethical or economic constraints of the new system. Utopianism is opportunity costThat means, counterintuitively, a diversion from contemporary problems: resources that would be devoted to innovations necessary for planetary habitability for an indeterminate period of time should instead be directed toward reducing carbon emissions and expanding green energy. Utopianism is not feasible, but it is also not desirable.

Related EconTalk Episodes

Zach Weinersmith talks about Beowulf and Be-Wolf

Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith talk about ‘Soonish’

Matt Ridley talks about how innovation works

Mike Munger talks about The Middleman