In my latest OLLI lecture, “Economic Growth: Important but Uncertain”, Posted I spoke on Substack, but I didn’t talk about one of the questions one of the participants asked. For some reason that question and my answer weren’t included in the video because John, the A/V guy, put in a certain cut, so I didn’t think to talk about it.

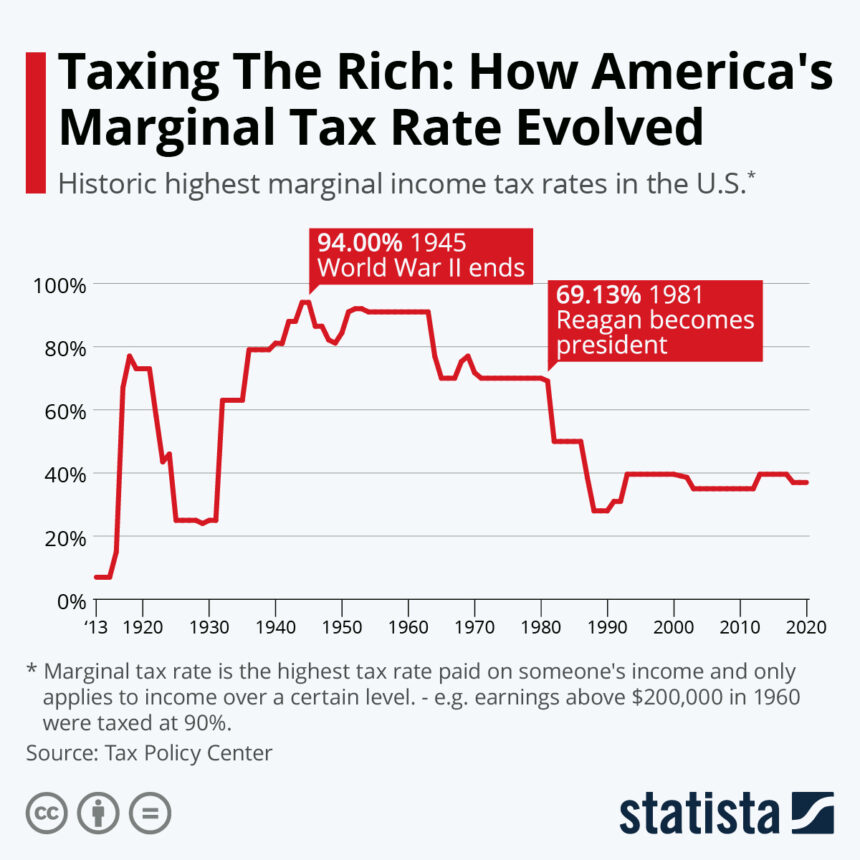

I took the audience on a quick tour of top marginal tax rates through the 20th century. from 7% when the first income tax was introduced. Under Woodrow Wilson, it was 77%. It fell to 25% under Treasury Secretary Mellon (which declined under the Harding and then Coolidge administrations), to 63% under Herbert Hoover, to 79% under FDR in peacetime, and at the end of the war under FDR. It has dropped to 94%. For most of the 1950s he dropped to 91% in the early 1960s, then to 70% under LBJ (as part of the Kennedy tax cuts), then in the early years of the Reagan administration he dropped to 50%. . Up to 31% under George H.W. Bush.

Of course, I made a more summary statement than the above, but the audience got the gist.

One of the people in the audience, a guy named Ed, said: “If marginal tax rates were high in the 1950s, doesn’t that mean economic growth was pretty good in the 1950s, so high tax rates don’t affect economic growth that much?”

I responded that the top marginal tax rate applies at such a high income level that it would take an adjustment for inflation to see how irrelevant it is for over 90% (probably over 95%) of earners. (I use “earners” in a broad sense; if you own stocks that provide a lot of dividend income, you count that income as earned income.)

I could have given a better answer if I had the data at hand, and I plan to do so now. But now he had left out one answer entirely. The economy of the 1950s was less regulated than it is today. It was much easier to get permits to build houses, bridges, pipelines, and office buildings. Also, the responsibility revolution that Walter Olson wrote about so well hadn’t happened yet, so producers didn’t have to expend as much effort to make their products foolproof. etc. All these positives can easily offset the negatives of high marginal tax rates on a small portion of the population. (One caveat: there was no deregulation of airlines, trucking, or railroads at the time, which hurt a bit.)

Now, let’s talk about tax data. The Tax Foundation provides tax bracket and tax rate data from 1862 to 2021. here.

Let’s look at the marginal tax rates in 1954. For married couples filing jointly, the marginal tax rate was 91% if their taxable income was over $400,000. For single people, the rate started at $200,000. This rate for the same income brackets remained the same from 1954 to 1963.

But $400,000 in 1954 was $4.66 million. Moreover, the overall real income distribution is now higher, perhaps at least twice as high. So this is like taxing a married couple with her $9.32 million taxable income at her 91% marginal tax.

Indeed, marginal tax rates were much higher than today’s tax rates, even for much lower incomes. Let’s think back to 1954. For a married couple with her taxable income of $24,000, their marginal tax rate was a whopping 43%. In today’s dollars, $24,000 becomes her $280,000. Therefore, my argument is not as strong as I originally thought. On the other hand, there was no Medicare tax and Social Security tax rates were much lower. In 1954, the SS tax on employers and employees totaled 4%, but now it is 12.4%. Plus, it was zero after earning $2,400 ($28,000 in today’s dollars).

I don’t have time to do the math or look at a lot of data, but this is just my guess: Until 1963, for over 80% of taxpayers in the top half of the U.S. income distribution, marginal tax rates, including Social Security and Medicare, were lower than for over 80% of taxpayers in the top half of the income distribution today.