This is Eve. Wolf Richter explains why the unemployment revisions are not unnatural or suspicious, but the exaggerated reporting is clearly poorly thought out and purposeful. That’s not to say it’s a good idea to turn the Fed into an inflation fire brigade.

Wolf Richter, editor Wolf Street. Originally Wolf Street

Our favorite recession indicators suggest the next recession is further down the road.

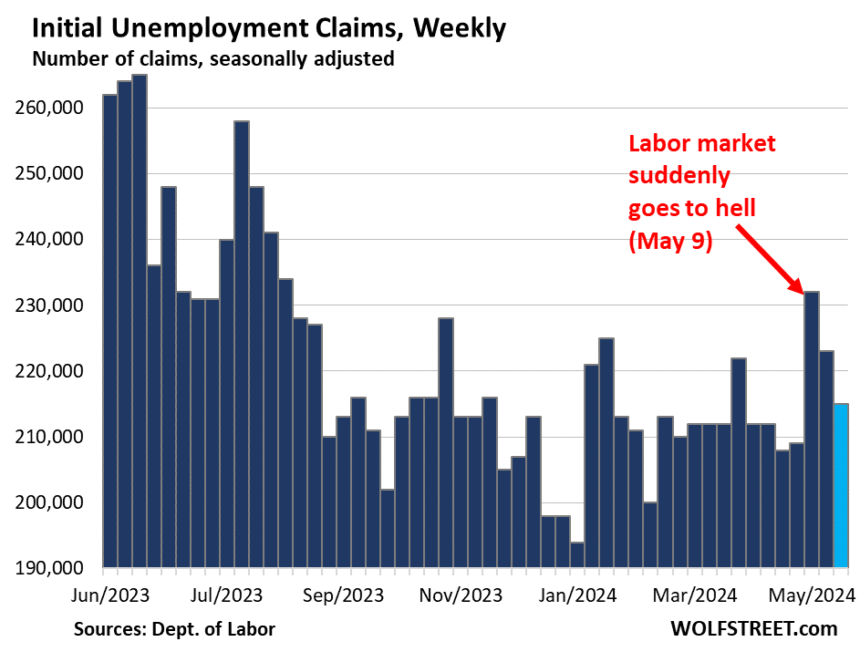

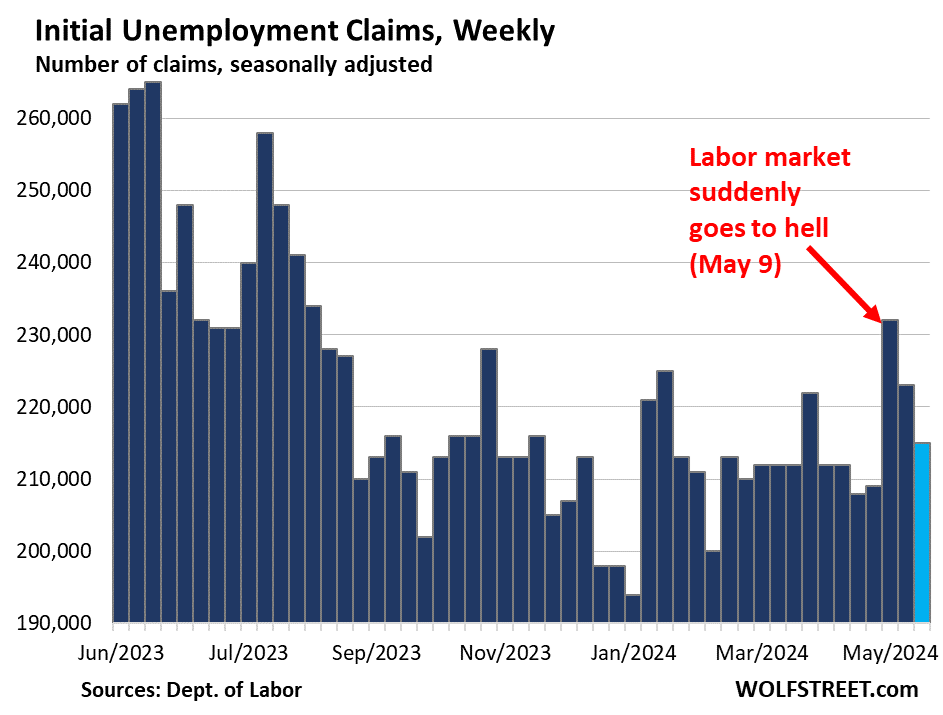

This is kind of interesting: According to data released this morning by the Department of Labor, new claims for unemployment insurance fell by 8,000 to 215,000 in the current reporting week, after falling by 9,000 in the prior week.

What’s interesting is the headline treatment of the spike to 232,000 two weeks ago (May 9th), which was heavily promoted as a sign that the labor market was suddenly weakening and that the Fed would soon start cutting interest rates. At the time, it was clearly underestimated.).

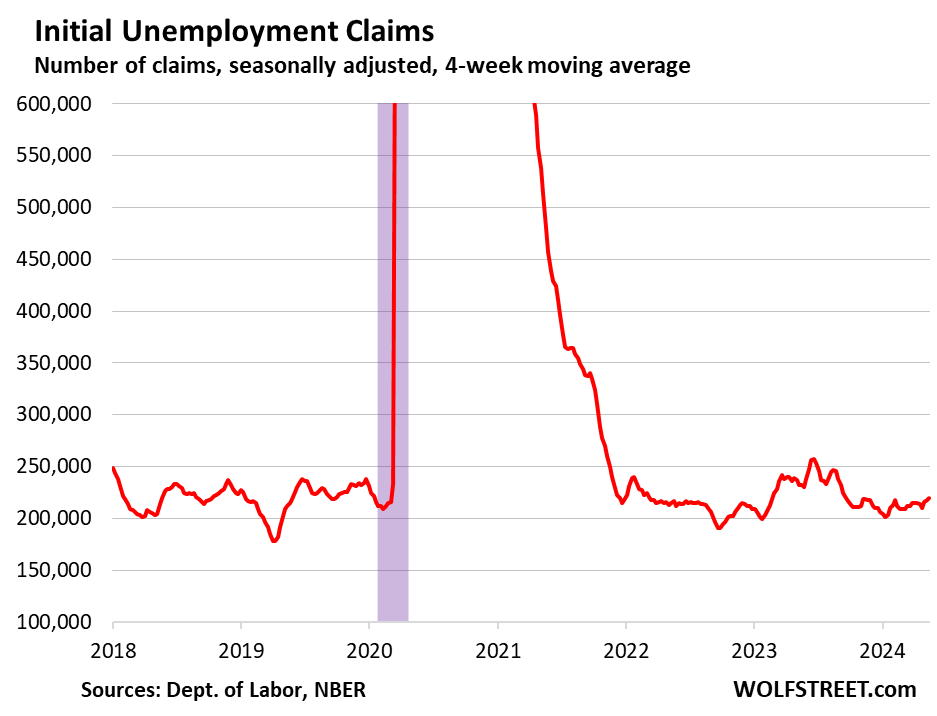

So today, initial claims for unemployment insurance returned to the historically low levels they had been at for the better part of the past two years, another sign of a relatively tight labor market. We take this data seriously, because it’s an ingredient in our favorite recession indicators (more on that in a moment).

One of the big reasons these initial unemployment claims data fluctuate so much from week to week is because it’s raw data on unemployment claims that newly laid-off people have filed with state agencies, which then process it and submit it to the Department of Labor before the weekly deadline.

One of the big reasons these initial unemployment claims data fluctuate so much from week to week is because it’s raw data on unemployment claims that newly laid-off people have filed with state agencies, which then process it and submit it to the Department of Labor before the weekly deadline.

“When the deadline passes, the claims are carried over to the next week, reducing the number of claims for the current week and increasing the number of claims for the following week. If Rhode Island did this, no one would notice a difference, but if one of the larger states did this, it would make a big difference from one week to the next.”

This is precisely why the Department of Labor also releases a four-week moving average, which adjusts for weekly fluctuations.

On May 9, the four-week moving average of initial jobless claims remained roughly steady at historically low levels before rising slightly to 215,000. We pointed out at the time.

Today, the four-week moving average rose to 219,750, but remains at historically low levels. The small peak that disappeared between February 2023 and September 2023 was the result of technology and social media layoffs.

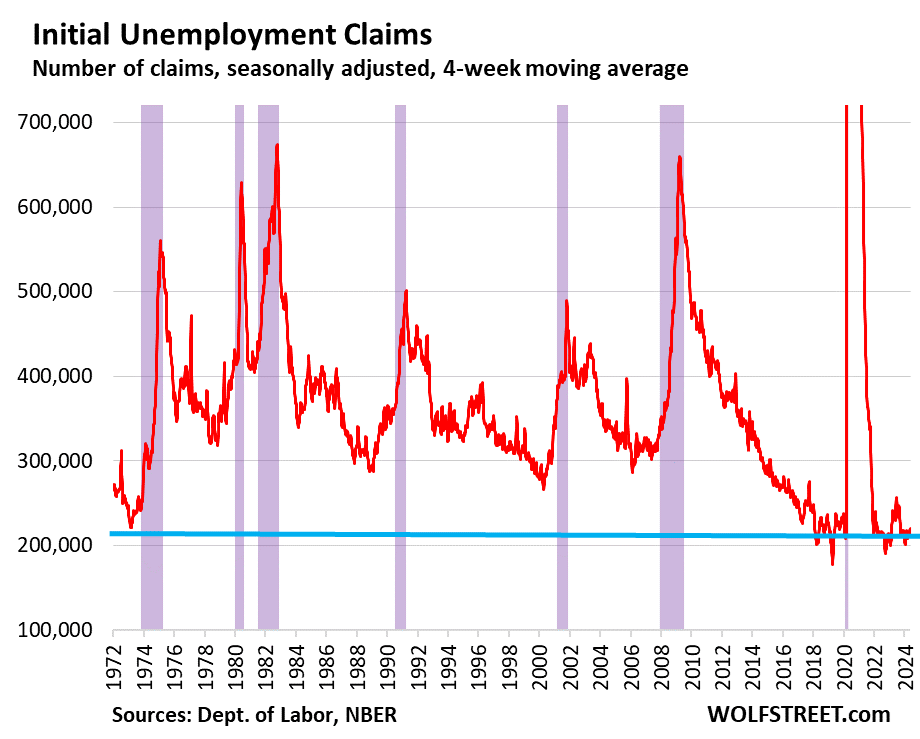

A longer-term view (recessions are shown in purple) shows how low first-time claims for unemployment insurance have been historically, especially considering that employment and the labor force have been growing along with the population for decades.

Our Favorite Recession Indicator

We have been watching for a recession ever since the Fed began raising interest rates in March 2022. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), which points out recessions in the US, has always defined a recession as a broad economic downturn that includes a weakness in the labor market.

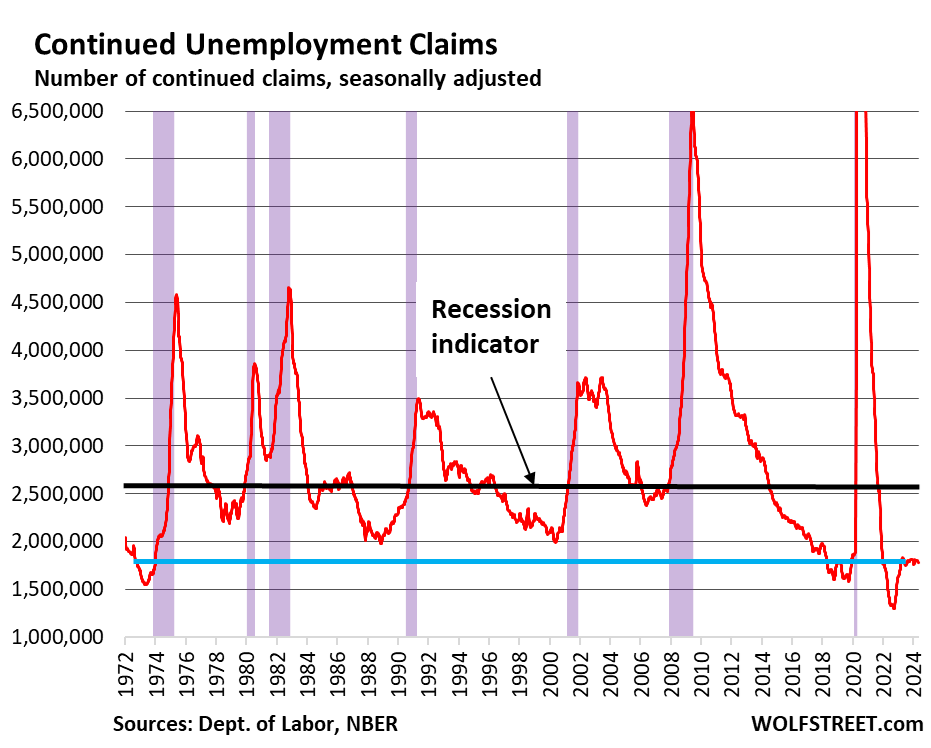

Therefore, we expect to see a surge in weekly claims for unemployment insurance benefits (top graph), and a surge in continuing claims for unemployment insurance (bottom graph).

The number of people who are still claiming unemployment insurance benefits at least a week after their initial claim — meaning they have not yet found work — has remained at relatively low levels since mid-2023.

This week’s report said 1.79 million people were still filing for unemployment benefits, with the four-week moving average remaining roughly steady at around 1.78, down slightly from December’s level of 1.81 million.

The high number of continuing claims suggests that it may take a little longer, on average, for unemployed people to find new work.

This pattern, which we have come to call the “frying pan” pattern, has been forming in many economic data sets due to the downside and subsequent normalization as we emerge from the pandemic.

Our indicator (below) shows that a recession is approaching when the blue line gets closer to the black line.

The Great Recession-turned-recession stretching back to the early 1980s began when continuing claims for unemployment insurance soared past the 2.6 million mark (black line in the graph below).

The current level of 1.79 million (blue line) is well below recession levels (black line), indicating that the labor market is the tightest it has been in the past 50 years and that there are no signs of a recession yet.