digitalhallway/E+ via Getty Images

A quick observation

When the fear of being left behind becomes especially extreme and the focus of speculation becomes especially narrow, certain characteristics of valuations, investor sentiment, and price action emerge, to varying degrees. These are the sources of these conditions. This is not a prediction, it is a statement about the current observable conditions.

“Noise reduction is the process of deriving a common signal from multiple partially correlated sensors, even if each individual sensor is imperfect. The reason we track these syndromes en masse is the same reason we benchmark internal markets based on thousands of securities: uniformity conveys information.”

– Dr. John P. Hussman Main veinNovember 20, 2021

Our investment discipline is to align our outlook to current measurable and observable market conditions, particularly valuations and market internals. It is difficult to change the outlook as the situation changes. In past market cycles, it was possible to respond immediately to extreme market situations such as “overvalued, overbought, and bullish,” which provided a kind of “limit” to speculation even before the market’s internal conditions clearly deteriorated. In the speculation caused by the zero interest rate policy, speculation has lost its “limit,” and the bearish response to the overexpansion syndrome has been abandoned. Exclude Inside the market Also The surprising consistency of adverse conditions – extreme valuations, adverse market internals, and a plethora of overextension syndromes – prompts tentative commentary.

Measured from the market peak in January 2022, the S&P 500’s total return underperformed Treasury returns through April of this year, while our proprietary valuations and market internal metrics remain unfavorable. The push to new highs over the past few weeks has given the impression of a runaway rally, as the market appears to be navigating the extreme valuations and unfavorable internal pitfalls with no consequences.

As I noted in late 2021, there are certain characteristics in valuations, investor sentiment, and price action that tend to emerge when fear of being left out becomes especially extreme and speculation becomes especially narrow in focus. Last Friday, we stumbled upon a new “mine” of these conditions. Since the mid-1980s, I have developed and collected a number of interesting syndromes and relationships that help me measure overextended conditions in both directions. From time to time I add, remove, or tweak one or two, but for the most part I have used the same set for years. The most significant change in 2021 was that market internal measures demanded worsening, regardless of how overextended conditions otherwise were.

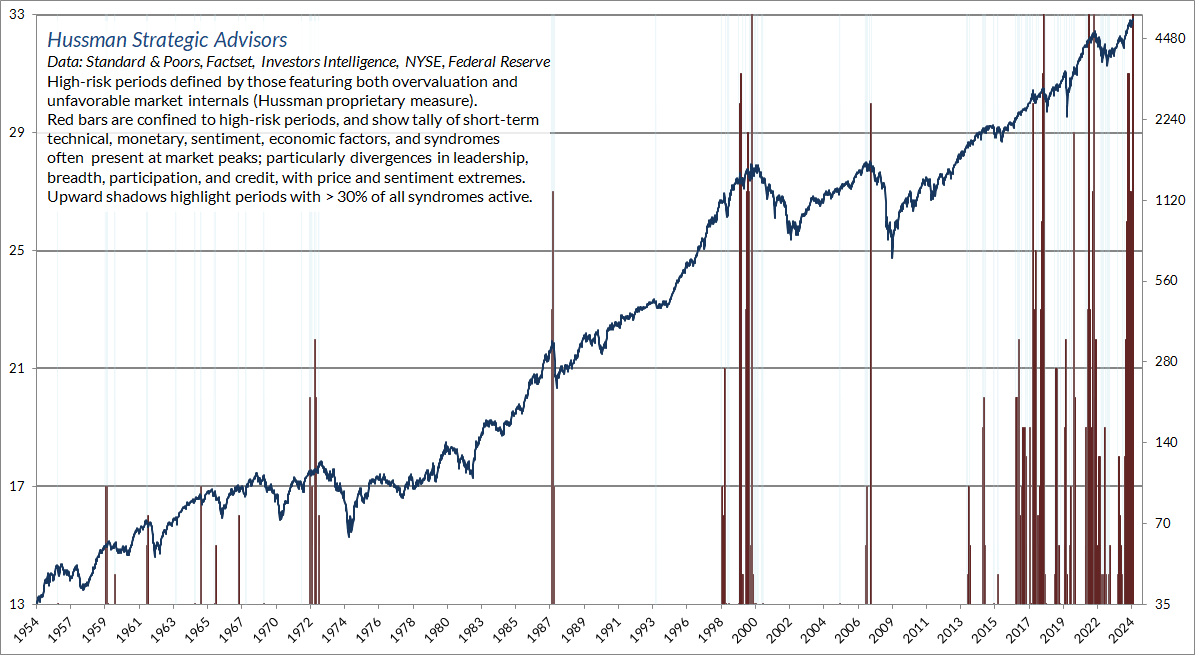

While we keep the internal market details and many technical indicators private, we are open about general characteristics. Red flags are usually a combination of overvaluation and price/volume trends, lopsided sentiment or speculative positioning, and divergences between individual stocks, industries, sectors, or security types such as bonds or low-rated credit. The chart below shows the current tally of overvaluation syndromes on weekly data. The blue line is the S&P 500 (right scale). The thin blue lines indicate periods when at least 30% of these syndromes were active.

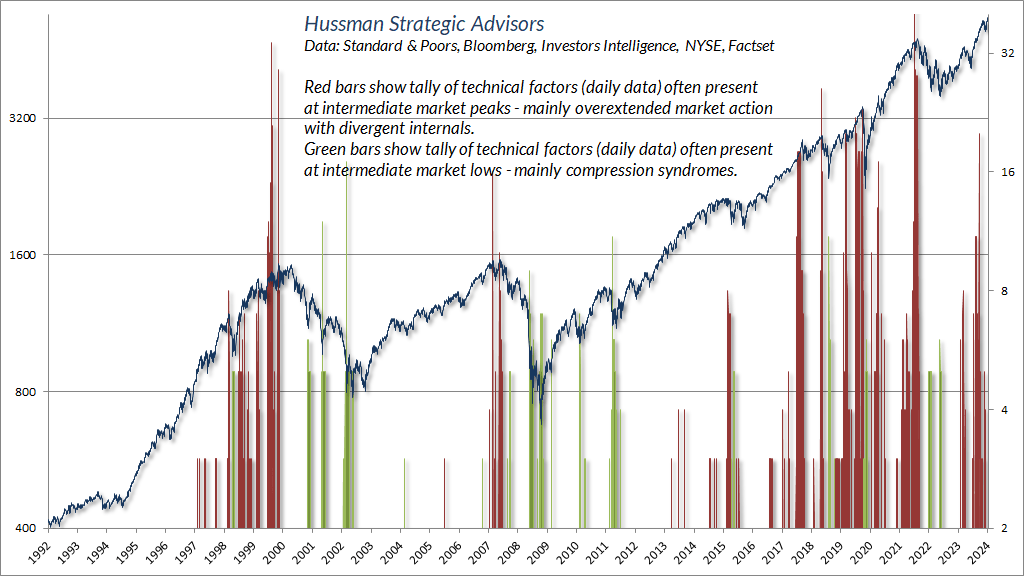

Over the past few months, I have expanded the set of comparable syndromes I monitor in my daily data, including the Downside Compression syndrome, which I have regularly described in Special Updates over the years. The red bars show an aggregation of technical factors common at medium-term market peaks, characterized primarily by divergent internal factors coupled with excessive market movements. The green bars show technical factors common at medium-term lows, characterized primarily by compression syndromes. The blue line is the S&P 500 (left scale).

The “final straw” of market trends worth monitoring in daily data today has to do with “leadership.” An increasing number of stocks hitting 52-week lows (as much as 2.5-3% of trading stocks) while major indexes are hitting new highs tends to be a hallmark of market fatigue. The reasons are the same as those I noted as we approached the market peak in 2007.

One of the best indicators of investor willingness to speculate is the “uniformity” of positive market trends across a wide range of internal factors. Over the years, I have noticed that significant market declines are often preceded by a combination of internal divergence, where individual stocks record a relatively large number of new highs and new lows simultaneously, and a leadership reversal, where the statistics shift from a majority of new highs to a majority of new lows within a small number of trading sessions.

“This is very similar to what happens when matter goes through a ‘phase transition’ – for example, from gas to liquid or vice versa. Some of the matter starts to behave distinctly, as if the particles are choosing between two phases. Then, as the transition approaches a ‘critical point’, one phase becomes preferred and we start to observe larger clusters as the ‘chosen’ particles influence their neighbors. We also observe fast oscillations between order and disorder in the remaining particles. Thus, a phase transition is characterized by internal dispersion followed by a reversal of initiative. I feel that this analogy also applies to the tendency of markets to experience increased volatility in 5-10 minute intervals before a significant drop.”

– John P. Hussman, PhD, “Market Internals Turn Negative,” July 30, 2007

I continue to believe that the market rally of recent months is an attempt to “catch the froth on yesterday’s bubble” rather than a new, sustained bull market rally, and that the S&P 500 may fall by around 50-70% by the completion of this cycle simply as long-term expected returns return to the mundane metrics that investors associate with stocks. However, as I point out in nearly every market commentary, usually using the word “resolutely,” our investment discipline does not depend on predicting short-term market trends or on valuations returning to long-term historical norms.

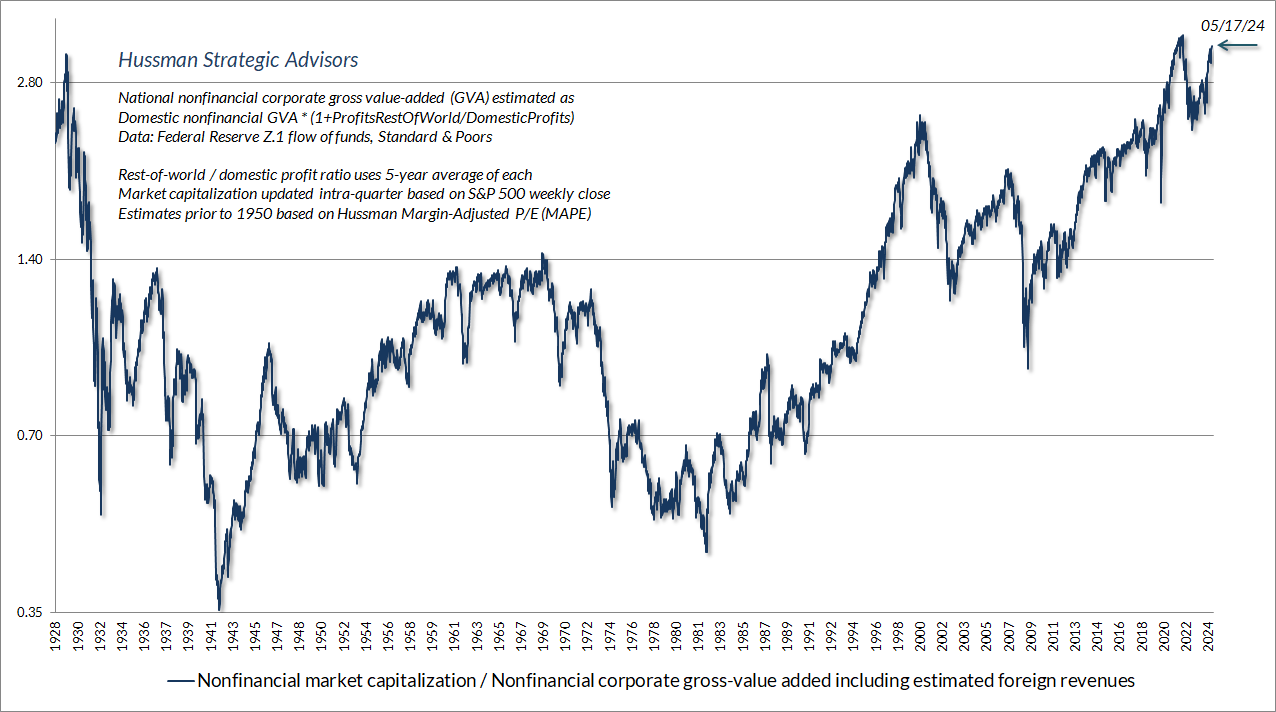

The chart below shows the most reliable valuation measure: the ratio of non-financial market capitalization to total corporate value added (including estimated foreign earnings). Current levels are above the extremes of 1929 and 2000, and above any point in US history except near the peak in early 2022. Even the more traditional (but less reliable) S&P 500 price to expected operating earnings multiple is unparalleled, except near the peak in 2000 and 2022. In simple terms, the impression is that the period since early 2022 is an extended peak of one of the three largest speculative bubbles in US history.

The S&P 500 has averaged an annual nominal total return of about 7.3% since 2000. This represents a 4.3% increase from nominal earnings growth, a 1.9% average dividend yield, and an additional 1.1% increase per year achieved by raising the S&P 500 price-to-earnings ratio from an extreme 2.2 in 2000 to an even more extreme 2.8.

Here’s the math: Price = Price / Earnings x Earnings. Mix those two ingredients. Add dividends. Serve chilled. Since 2000, investors have squeezed more out of 4.3% earnings growth and 1.9% dividends. only By driving price-to-earnings ratios to record extremes. Then, when you move valuations in the opposite direction, the pullback in valuations acts as a subtraction to long-term returns. The calculation is the same for other valuation multiples. While fundamentals such as earnings are noisy, much of that noise is driven by fluctuations in profit margins, which reflect immutable changes in interest costs and cyclical fluctuations in real unit labor costs.

Clearly, investors need not require historically normal long-term returns. Assuming that nominal returns continue to grow at 4.3% per year, and adding the current S&P 500 dividend yield of 1.4%, a “forever high” valuation implies that the long-term expected nominal total return for the S&P 500 is estimated at about 5.7% per year. Needless to say, I view that estimate as highly optimistic, especially since history has generally disproved the notion of “forever high.”

While the most reliable valuation indicators are 2.8-3.2 times the historical norm, any exposure to these norms after 10 years would imply a 9.8-11.0% annual deduction from the 5.7% baseline, with annualized total returns in the range of -4.1% to -5.3%. Again, this is just math. Even a slight retreat from the “permanently high plateau” would bring the 10-year estimated total returns down into the low single digits. With the current valuation extremes, it is almost impossible to imagine how far passive investing popularity and expectations for long-term equity market returns could rise. rely Based on the assumption that valuations will remain durable and continue to rise.

On the other hand, if we expect higher returns to come from nominal growth due to unchecked inflation, it is instructive to examine valuation behavior during periods of inflation, both in the United States and elsewhere. In general, stock prices only benefit permanently from high inflation. rear Valuations have been pushed down to low levels. At present, the Consumer Price Index is triple The positive impact of inflation on nominal fundamentals is expected to outweigh the negative impact of rapid and persistent inflation on valuations.

For more information on the calculations that link valuation, cash flow, and long-term investment returns, Structural factors behind investment returnsFor more information on the returns and trends of attractive stocks of large companies, Universal Surrender and No Safety Margin.

Finally, as in every speculative episode in history, there is a narrative of “innovation” that lures investors into believing that “this time is different.” As Business Week wrote in 1929, “The illusion is summed up in the word ‘New Era.’ The word itself is not new; in every period of speculation it is rediscovered.” With wild speculation flying from all sides, a few observations may serve as a reality check.

- The biggest driver of margin expansion in recent decades has not been technological innovation, but lower interest costs that were temporarily locked in by massive refinancings in 2020 and 2021.

- The growth rates and operating margins of attractive stocks of large companies are not fixed numbers, but trajectories.

- Long-term growth of the economy as a whole everytime Driven by innovation and productivity, cutting-edge companies initially enjoyed high profits and growth rates, but cycles of creative destruction repeated themselves as new industries expanded.

- If S&P 500 total income and U.S. GDP have averaged real annual growth rates of less than 2.5% over the past 30 years, Despite all the innovation While (and it is), and we can demonstrate that rising corporate profit margins over that period are primarily related to falling interest costs, (we can demonstrate), it would be a mistake to value the entire market at record multiples simply because a few companies are enjoying network effects and monopolizing market share; cash flows are simply concentrated in a few hands.

- Network effects and near-monopolies can slow or postpone erosion of profit margins, but they cannot eliminate long-term competition (as every giant corporation that has gone bankrupt throughout history attests to).

Our own investment discipline is to respond to changing market conditions over time. The adaptations we have put in place in 2021 have encouraged an aggressive outlook (for example, I was frequently leveraged in the early 1990s) or a constructive outlook (perhaps with position limits or safety nets) in about two-thirds of the historical period, and in more than half of the period since the 2009 market lows. Constructive market conditions will emerge soon, even if localized and sporadic at first. We have not observed such conditions here at all.

Editor’s note: The summary bullet points for this article were selected by Seeking Alpha editors.