Lambert: Hold on a second. Cartels… “consumer welfare”… I remember something, but I’m not sure…

By Marit Hinosar (Assistant Professor, University of Nottingham) and Toumas Hinosar (Centre for Economic Theory, University of Nottingham). Originally published on VoxEU.

Social media influencers are making up an ever-increasing share of marketing budgets worldwide. In this column, we examine a problem in this rapidly expanding advertising market: influencer cartels. In influencer cartels, groups of influencers collude to inflate each other’s engagement numbers to increase advertising revenue. Influencer cartels can improve consumer welfare by expanding social media engagement to their target audiences, but reduce welfare by diverting engagement to less relevant audiences. Rewarding engagement numbers encourages harmful collusion. Instead, the authors suggest that influencers should be compensated based on the value they actually deliver.

Imagine a university that rewards professors according to the number of citations their work receives. In response, a group of colleagues might agree to cite each other’s work in every paper they write. What would be the positive and negative aspects of this hypothetical citation cartel? Economists are not known for over-citing. This can be explained by a positive externality: the citing author bears all the costs and the cited author benefits. The citing authors are unable to internalize this positive externality, and so end up receiving fewer citations than would be socially optimal.

Citation cartels can solve this problem through reciprocity: a cartel agreement ensures that members receive as many citations as they give. However, this can go too far: if the agreement requires citing unrelated papers, it may be good for the members of the group, but it may lead to meaningless literature reviews. Thus, the benefits of such an agreement depend on its nature: putting more effort into citing relevant papers may be good, but citing unrelated papers is probably bad.

Such an academic citation cartel is not just a hypothesis: academic journals have been found to have agreements to boost each other’s journals in the rankings (Van Noorden 2013). Similarly, universities have boosted the citation counts of their colleagues to improve their university rankings (Catanzaro 2024). Such citation patterns have led Clarivate (Thomson Reuters) to remove the journal from its impact factor list, and more recently the entire field of mathematics (Van Noorden 2013, Catanzaro 2024).

Academic citation cartels are difficult to study due to the lack of data on explicit cartel agreements. But in influencer marketing, cartel agreements are observable. In our new paper (Hinnosaar and Hinnosaar 2024), we study how influencers collude to inflate engagement and the conditions under which influencer cartels improve welfare.

Perverse incentives and fraud in influencer marketing

Influencer marketing has become a key part of modern advertising. By 2023, spending on influencer marketing will reach $31 billion, already rivaling all of print newspaper advertising. By selecting the right combination of products, influencers, and consumers, influencer marketing allows advertisers to finely target consumers based on their interests.

Many non-celebrity influencers are not compensated based on the success of their marketing campaigns. In fact, less than 20% of companies track sales induced by their influencer marketing campaigns. Instead, influencers are compensated based on their influence, such as follower counts or engagement (likes and comments), creating an incentive to commit fraud, i.e., to exaggerate their influence. Influence exaggeration is a form of advertising fraud that creates market inefficiencies by directing advertising to the wrong audience. An estimated 15% of influencer marketing spend is misused for exaggerated influence. To address this issue, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission proposed rules in 2023 to prohibit the buying and selling of false metrics of social media influence. Cartels do not fall directly under the proposed rules because no money changes hands, but they offer a way to obtain fake engagement in the same spirit. While there is a large literature on fake consumer reviews (Mayzlin et al. 2014; Luca and Zervas 2016) and other forms of advertising fraud (Zinman and Zitzewitz 2016), the literature on influencer marketing has focused primarily on advertising disclosure (Ershov and Mitchell 2023; Pei and Mayzlin 2022; Mitchell 2021; Fainmesser and Galeotti 2021) and has not studied fraudulent behavior.

How does Instagram Cartel work?

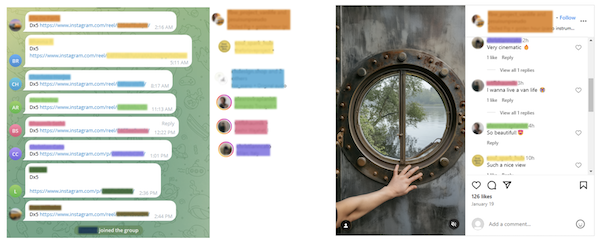

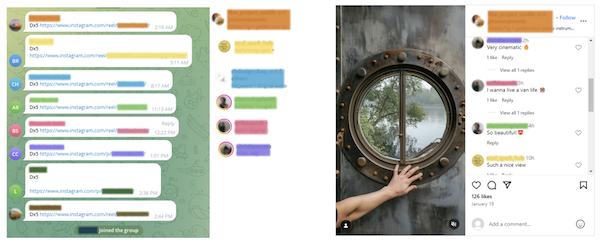

Influencer cartels are groups of influencers who conspire to inflate engagement metrics and drive up advertising fees. As in traditional industries (Steen et al. 2013), influencer cartels involve formal agreements to manipulate the market for the benefit of their members. Cartels operate in online chat rooms. The screenshots below show how such cartels work in practice. The image on the left is from an online chat room where cartel members send links to their content to boost engagement. Before sending the link, members must respond to other members’ posts by liking or commenting on them. An algorithm enforces these rules. The image on the right shows these comments caused by the cartel on Instagram. The cartel’s history and rules allow us to observe which engagements (comments) came from the cartel.

Figure 1 The left panel shows online chat room posts submitted for interaction with the cartel, while the right panel shows Instagram comments from the cartel.

sauce: The left panel is a screenshot of a Telegram group, and the right panel is a screenshot of an Instagram account. To preserve anonymity, account identifiers have been blurred and photos have been replaced with similar ones by an AI image generator.

What distinguishes a “bad” cartel from a “not so bad” one?

Our theoretical model formalizes the main trade-offs in this setting in the spirit of the fictitious citation group mentioned above. The model focuses on strategic engagement, a decision that impacts the distribution and consumption of social media content (Aridor et al. 2024) but has been underexplored (except for Filippas et al. 2023, who studied attention exchange on Twitter). Engaging with other influencers’ content has a positive externality and leads to too little engagement in equilibrium. Forming a cartel to mutually engage with each other’s content may internalize this externality and be socially desirable. However, it may also lead to less valuable engagement, especially if advertisers pay based on quantity rather than quality.

A key aspect that distinguishes “bad” cartels from “not so bad” cartels is the quality of the cartel’s engagement. “High quality” means engagement from influencers with similar interests. The idea is that influencers provide value to advertisers by promoting their products to a target audience with similar interests, such as promoting a vegan burger to vegans. When a cartel generates engagement from influencers with other interests (meat lovers), it harms consumers and advertisers: consumers harm because the platform shows them irrelevant content, and advertisers harm because their ads are shown to the wrong audience. Whether a particular cartel reduces or improves welfare is an empirical question.

Assessing engagement quality using machine learning techniques

To answer this empirical question, we use new data from influencer cartels and machine learning to analyze Instagram texts and photos. The cartel data allows us to directly observe the Instagram posts included in the cartels and the engagement (via cartel rules) that originates from the cartels. The dataset contains two types of cartels, differentiated by their cartel entry rules: topic cartels (which only accept influencer posts on a specific topic) and general cartels (which have no topic restrictions).

Our goal is to compare the quality of natural engagement with the quality of engagement that comes from cartels. We measure the quality by the topic match between cartel members and engaging Instagram users. To quantify the similarity of Instagram users, we use a large-scale language model (language-agnostic BERT sentence embeddings) and a similar large-scale neural network (contrastive language image pre-trained model) to generate numerical vectors (embeddings) from the text and photos of Instagram posts. We then calculate the cosine similarity between Instagram users based on these numerical vectors.

Can cartels improve welfare?

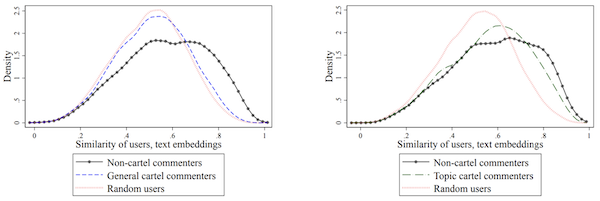

We find that engagement from general cartels is significantly lower in quality than natural engagement. Specifically, the quality of engagement from these cartels is almost as low as counterfactual engagement from random Instagram users. In contrast, engagement from topic cartels is much closer to the quality of natural engagement.

The figure below illustrates these effects using the raw data (see the paper for regression estimates, robustness checks, and additional analysis). It shows the distribution of cosine similarities between authors and commenters for general cartels (left panel) and topic cartels (right panel). We can see that non-cartel commenters (natural engagement) are most similar to content creators, and random users are the least. Match quality from general cartels is similar to random engagement (left panel). In contrast, topic cartel engagement is very close to natural engagement (right panel).

Figure 2 Probability density of similarity between authors, commenters, and random users in general cartel (left) and topic cartel (right)

Rough calculations (based on regression analysis) suggest that if advertisers paid the same for cartel engagement as they did for natural engagement, they would only get 3-18% more value from general cartels and 60-85% more value from topical cartels. In other words, general cartels provide engagement that is almost worthless to advertisers, while topical cartels cause less distortion.

Conclusions and policy implications

Our findings lead to three policy implications. First, because common cartels are likely to reduce welfare, increased regulation of their activities would benefit society. Second, regulations banning the buying and selling of fake social media metrics should also cover in-kind transfers, such as payments for engagement via reciprocal engagement. Third, the current practice of rewarding the amount of engagement encourages harmful collusion. A better approach would be to reward influencers based on the actual value they provide. Fortunately, many advertisers are already moving in this direction. Until they get there, platforms can improve their results by reporting engagement weighted to the quality of matches.