Today’s jobs report contained two pieces of information that suggest policy may be a little too expansionary. First, the number of payroll earners increased by 272,000, better than expected (the household survey was weak, but that data is considered less reliable). Second, nominal wages increased by 0.4% (about a 5% annual rate). From the perspective of the Fed’s dual mandate, both data points lean a little bit toward policy being too expansionary. This does not mean we can be certain that policy is too expansionary, but rather that the likelihood of this assertion being true has increased a little.

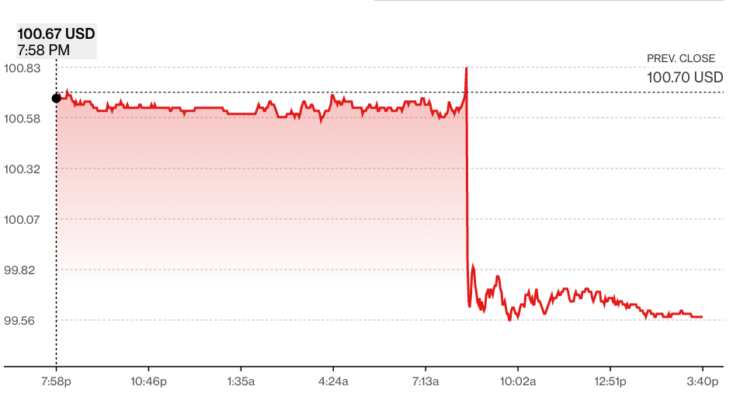

The 10-year Treasury market responded to selling pressure, pushing longer-term interest rates higher.

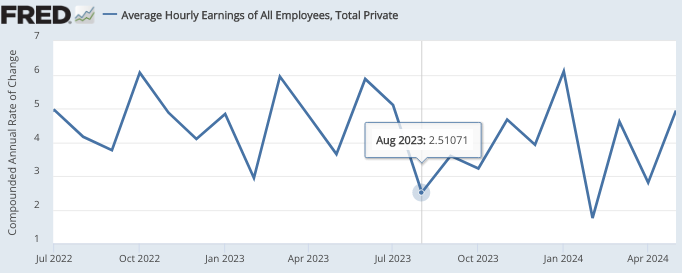

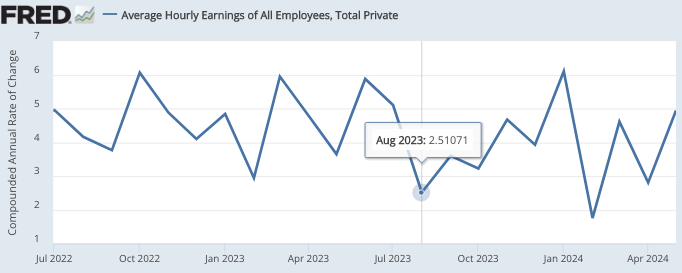

Markets currently expect the Fed to cut rates later this year. This could happen because of falling inflation or because the real economy is at risk of slipping into recession. Today’s news makes either outcome seem a bit less likely. Wage inflation has averaged 4.1% over the past 12 months, which is not consistent with the Fed’s “price stability” goal, even if price stability is defined as 2% inflation. Over time, wage inflation tends to exceed price inflation by around 1% to 1.5%. Unfortunately, progress toward reducing wage inflation appears to have stalled over the past 10 months. The next couple of readings will be very important.

I don’t have a clear view on where the Fed should set its interest rate target at this point. However, I do have a clear view on past monetary policy, as the past three years of monetary policy have been overly expansionary. The longer these policy excesses continue, the stronger the case becomes for the Fed to switch to a level-targeting policy regime that promises to make up for past policy mistakes. I thought that’s what the Fed intended to do in 2020, but it turns out that “average inflation targeting” was not an accurate representation of the new policy regime.

Despite the title of this article, “Double Trouble,” the payroll numbers can be considered good news. These numbers are troubling for the Federal Reserve, which seems to be hopeful that it can lower its target interest rate soon. In my view, it was a mistake for central banks to favor low interest rates, and it was also a mistake for the Fed to favor high interest rates in 2015. The Fed should prioritize macroeconomic (nominal) stability, rather than prioritizing either low or high interest rates. Let the market decide what interest rates are consistent with macro stability.

P.S.: This comment FT Things that caught my eye:

Jason Furman, a former administration official now at Harvard University, said the rising unemployment rate could be the most important part of Friday’s data release.

“If the unemployment rate is 4.1% next month, (the Fed) will take notice,” Furman said. “If the unemployment rate is above 4%, you’ll see a faster cut in interest rates.”

In the 1970s, the Fed assumed that rising unemployment was a sign of monetary tightening. But that wasn’t the case. The Fed shouldn’t target the unemployment rate, because no one knows exactly what the natural rate of unemployment is at any given time. The Fed should target a nominal variable, preferably nominal GDP. It’s true that rising unemployment is often a signal that monetary easing is needed, but not when NGDP is growing at 5%.