RHJ

Uranium stocks are unique within the energy industry because they face economic fundamentals that are vastly different from others. Further, the North American uranium mining industry is prone to immense speculation from retail investors, as the sector is generally unprofitable (particularly in the US). Most global uranium supplies come from Kazakhstan through dominant firms like Cameco (CCJ).

Since uranium is prone to huge boom and bust cycles and has less straightforward economics, it is often caught up in misconceptions or excess positive or negative outlooks. This is understandably the result of immense market volatility and speculation in the sector, particularly regarding the potential for more North American uranium mining companies to become profitable as prices rise.

Further, many investors have a bullish take on uranium due to their positive outlooks on nuclear energy. In my opinion, the performance of uranium miners may not be associated with the potential growth of nuclear energy, stemming from the immense time lag for nuclear construction and the high potential supply of uranium ore.

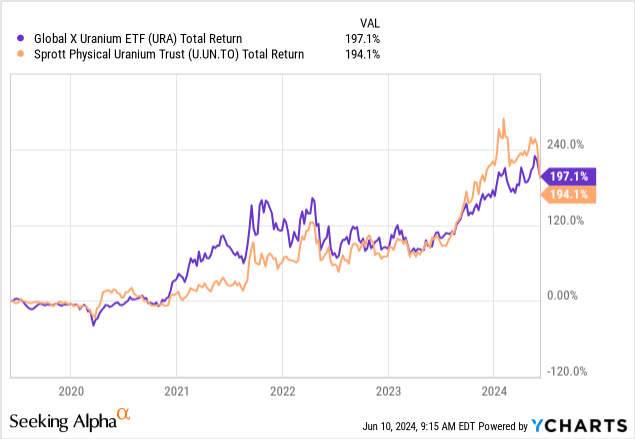

The industry faced significant positive momentum last year, with uranium ore being among the very few energy commodities to rise. The popular uranium ETF (NYSEARCA:URA) is up 40% YoY, benefiting from a large wave in hedge fund buying activity. URA is up by ~197% over the past five years, with the uranium physical commodity ETF (OTCPK:SRUUF) (the US OTC Ticker for Sprott Physical Uranium Trust) up by a similar degree. Notably, URA and the physical commodity have slipped in recent weeks following a stagnation in uranium prices over the past five months. See below:

In December of 2023, I published a neutral outlook for the uranium miner ETF (URNM), followed by a bearish outlook on its primary holding, Cameco (CCJ). CCJ is also the largest holding in the more popular uranium ETF URA at ~26% of its assets. CCJ has risen since I covered it last, but uranium prices have stagnated and declined, with many smaller miners slipping. To me, that indicates the market may be becoming further dislocated from its fundamentals, pointing to declines for the industry.

That said, some market aspects have changed in recent months, so I believe it is a good time to cover the popular uranium ETF (URA) to provide an updated outlook. Previously, I was neutral on URA after being bullish from 2019 to 2021, earning a sizable gain over that period.

Nuclear Demand is Unlikely To Rise Soon

In my opinion, some of the bullish arguments surrounding URA are not well-founded in the industry’s economic fundamentals. For example, analysts or investors often point toward AI as increasing demand for power and then assume that nuclear must be that power source, implying that uranium prices will rise and increase the profits and valuations of uranium miners.

I’ll assume that US power demand will rise, given some analysis that points toward a ~20% increase in demand by 2030 from AI data centers. Still, it is unclear if AI will see that speed of demand growth. That said, I do not think this is important for uranium because there is an even greater time between power demand and nuclear power plant development.

It takes around 7.5 years to construct a nuclear and longer if we consider planning and regulations. Further, that data is primarily based on construction times in Asia, where nuclear is growing the fastest, as US nuclear power has steadily declined in recent years. The most recent US nuclear plant in Georgia was completed seven years late and cost over twice as much as the initial estimate. In other words, America’s first new reactor in over thirty years took fourteen years to build, implying the US is nowhere close to the speed of China for nuclear plant construction.

Nuclear power is not economical, with Lazard estimating its Levelized Cost of Energy to be around $182/MWh. In order, onshore wind, geothermal, coal, and utility-scale solar are cheaper. The only power source with a lower return is residential rooftop solar, which benefits from theoretically lower transmission needs. It could be argued that nuclear power plants’ total scale and lack of greenhouse gases make up for their lower ROI. However, the fact is that nuclear plants are incredibly capital-intensive (an issue with high interest rates), take a very long time to plan and build, and have immense ongoing labor overhead costs (a problem with inflation).

Further, decommissioning is expected to accelerate over the coming decades due to aging nuclear plants in much of the developed world. Some hope to extend their lives, but many are too costly to operate.

Arguments may be made about why nuclear is still a viable future power source. Indeed, the Biden administration has recently shifted to support developing and maintaining nuclear plants. Still, even if there is a significant renaissance in US and European nuclear power, that likely will not result in a rise in uranium demand until the 2040s to 2050s, given the timeline of these projects. On the other hand, renewables like wind and solar are seeing steady double-digit annual growth, with significant expected acceleration over the coming five years.

Uranium Economics Bearish For URA

Uranium is not like oil, as it is far more abundant globally. According to an NEA study, there is likely around 230 years of supply of uranium resources available at the 2009 consumption level. Although that study is well over a decade old, it remains relevant as there have not been significant changes in uranium supply and demand since then. That study also noted that technological improvements in extraction and exploration were likely to double that estimate over time. Further, it noted that if a method for extracting uranium from seawater were found, there would be over thirty thousand years of available supply.

I’m sure some could argue the specifics, but the fact is that uranium supply is not a constraint on nuclear power. That may make nuclear power a viable clean energy source, particularly decades into the future, but that does not make uranium mining profitable.

Keep in mind that the uranium demand curve is theoretically completely inelastic. Power plants will not decrease demand with higher prices of raw ore because raw ore costs are negligible compared to enrichment costs, and even enriched uranium is a low overall cost of operating a plant (compared to skilled labor). This benefits URA by implying higher uranium ore prices will not result in lower demand.

However, since many semi-developed uranium mines in the US are not operating, the supply curve is likely very elastic. There is some debate on this point, but most studies point to an exponential potential increase in supply as uranium crosses over into the $100 to $150/lbs range. Remember that demand is essentially stagnant today, with annual global demand growth forecasted at ~1%.

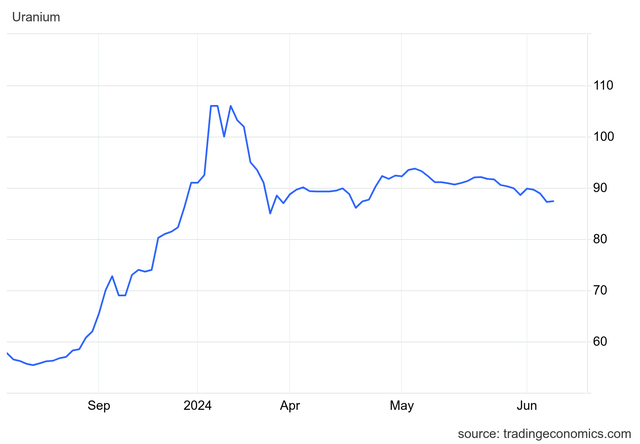

Thus, now that uranium is floating around the $85/lbs to $100/lbs range, many US miners are finally restarting production. All of the necessary data regarding supply and demand are not public. However, I believe it is a virtual certainty that the impending output growth from US miners will be greater than demand growth, which is negligible.

I believe Uranium prices are not rising due to increasing climate-change-related demand, as some media outlets have popularized. It is also essentially not correct that US mines are restarting because of lost Russian resources. The US wants to grow its uranium enrichment base to lower its dependence on Russian enrichment facilities. In the long run, that may benefit US ore miners, but again, enrichment is, by orders of magnitude, the costlier part of the uranium fuel cycle than mining.

In reality, the 2023 spike in uranium prices is primarily the delayed result of a supply and demand imbalance created by Cameco’s temporary closure of MacArthur River and Cigar Lake, major global supply sources from Canada. Since these are North American uranium mines, they have much higher operating costs than those in Kazakhstan. Thus, Cameco will often cut production from those facilities if uranium prices are below $70/lbs (roughly). However, due to COVID lockdowns and related supply and labor issues (lasting into 2023), the company had difficulty restarting production, leading to a supply shortfall. The Niger Coup may have slightly exacerbated this shortfall, but Kazatomprom quickly said they would increase exports (from Kazakhstan) to make up for any Niger-related shortfalls.

So, with Kazatomprom and Cameco now having normalized production and Cameco looking to expand its output, the supply gap is likely to close. Around Q3 to Q4 of 2024, US supplies are anticipated to increase due to the restarted mines. To me, this will likely push the uranium market back into a persistent supply glut by 2025-2026. Thus, uranium prices are resistant to rising over the $90-$100 range, where most North American miners can break even. See below:

Uranium Futures Price (USD/LBS) (TradingEconomics)

In my opinion, the economic law of the zero-profit condition holds true in the uranium market. Imagine the global uranium mining industry dominated by an oligopoly of Cameco, Kazatomprom, Orano, CGN, and Uranium One, collectively controlling around two-thirds of global supplies. Mostly, these companies share ownership of numerous mines in Kazakhstan and Canada and are prone to cutting production when prices decline. This creates a long-term uranium price floor of around $40/lbs to $70/lbs in today’s market, which is high enough for Kazakh mines to profit but just below the North American breakeven levels. As prices cross above that level, we’re seeing more small North American miners (of which there are many) look to ramp up production. Thus, looking forward, it is very likely that output will rise above demand, creating a price ceiling of around $100/lb.

The issue with URA is that most of its holdings are in North America and Australia, where uranium is around that zero profit condition today. Besides the quarter of the fund in Cameco (which has consistently profitable mines outside North America) and the 7.5% of the ETF in Sprott Physical Uranium, the remaining two-thirds of the fund is in the many small mines that have no oligopoly pricing power.

Many of these mines are likely to be profitable today. However, if they all act on that and raise production to earn a profit, I believe it is virtually certain that supplies will rise above demand, pushing uranium back below $70/lb, resulting in significant losses. For example, the forward EPS outlook for Uranium Energy Corp (UEC) and Denison (DNN) (two top-ten URA holdings) is -$0.01 and -$0.03, respectively, indicating they’re at breakeven with uranium around $90 but will face losses should it decline. Again, I would be surprised to see uranium rise above $100 and remain that high outside of a geopolitical crisis in Kazakhstan.

With the market where it is, I see no reason to invest in uranium miners as I expect they will face losses over the coming two years as their renewed output pushes the market into a glut. Again, there is zero reason to believe uranium demand will increase in the coming years, let alone in the coming decades, so a slight supply increase would quickly create a glut. For the same reason, I continue to believe Cameco is wildly overvalued, mainly because its supply contracts will greatly inhibit it from profiting from the 2023 uranium rally. I think uranium prices will decline by the time the bulk of its contracts roll forward, largely because of Cameco’s renewed output levels.

One notable positive point regarding Cameco is its Port Hope conversion facility, which converts uranium to UF6 fuel. This is one key asset that should benefit from the effort to move away from Russian-converted to fuel. Although I expect this facility to earn higher profits, I do not believe it can offset the glut risk in the broader mining space.

The Bottom Line

Overall, I am bearish on URA today and believe the uranium mining sector is quite overvalued, given the significant risk that the market will shift back into a glut by the end of this year. CCJ and chronically negative-cashflow North American uranium miners seem to have the most significant downside risk, given it seems excessive investor exuberance surrounding uranium, which I believe is not well-founded in economic fundamentals.

That said, there is one circumstance where I could become very bullish on URA, which is not necessarily a very low-probability event. So much global uranium comes from Kazakhstan specifically, as well as Africa. Kazakhstan has a risk of unrest and instability. It is also closely tied to Russia and is part of its CSTO military alliance.

While Western political leaders are primarily concerned with Russian import dependence on enriched uranium, that issue could shift toward Kazakhstan’s import dependence on uranium ore. Indeed, should Kazak uranium imports to the EU and the US stop today, it could create a crisis as although North America (and Australia) has significant potential uranium, the mines have not ramped up output fast enough to offset this. Thus, there is strong reasoning that the US should and will prop up its uranium miners for national security. Indeed, this was a significant issue that the Trump admin had worked on, which had made me bullish on US miners in 2019.

So, while the current economic situation does not seem to be bullish for URA, that could change on a dime with global geopolitics. At this point, there is no talk of stopping Kazakhstan imports. However, with Biden’s potential pro-nuclear and uranium security shift and Trump’s historical focus on this issue, I think there is reason to speculate. Still, I am not convinced the valuations of many North American miners are sensible, but if uranium rises into the $200+ range due to a supply crisis from Central Asia, then that could change.