This is Eve. We have been warning for some time that the Fed would have to gut the economy to stop this inflation. The recent price rise is not the result of a typical wage-driven cost spiral; workers’ bargaining power remains fairly weak. Instead, it has been driven by Covid and other supply shocks in certain sectors (remember when egg prices skyrocketed in the US because of chicken culls?), further supply tightness due to sanctions, companies raising prices because they can, and most recently, the administration choosing to run the economy super-hot through huge budget deficits.

Broadly speaking, the Fed would have to go too far to tame inflation that simply raising interest rates would not be enough, and as this article explains, there are growing signs that this will indeed happen.

Authors: Thomas Ferguson, Research Director at the Institute for New Economic Thinking and Professor Emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and Servaas Storm, Senior Lecturer in Economics at Delft University of Technology. Institute for New Economic Thinking website

June 13thNumberThe financial markets are Overestimated the possibility The Federal Reserve will soon cut interest rates. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s press conference comments, along with the Federal Open Market Committee’s recently updated quarterly “Summary of the Economic Outlook,” strongly suggest the conclusion that the Federal Reserve will probably cut interest rates only once before the end of 2024.

In the midst of this historic surge, the US financial markets could only sigh. The reaction in other countries was less optimistic. Some international commentators were concerned that if US interest rates remained high for a long time, it would make it harder for foreign countries to repay dollar-denominated loans, accelerating capital flight from developing countries. But even in the US, Retail sales disappoint, Housing construction slowsThe impact of high interest rates for a long period of time on the average consumer, weakness in commercial real estate holdings held by many banks, and signs of a gradual tightening of the economy. Economist Claudia Thurm, who has warned that unemployment will rise slowly, summed up many of these concerns:My base case is not a recession, but it is a real risk and I don’t understand why the Fed is pushing it. I don’t know what they’re waiting for…The worst possible outcome at this point is that the Fed creates an unnecessary recession.”

The Fed has an easy answer: they’re worried that U.S. inflation will remain high for some time to come. Inflation remains high overall, but the main reason is a persistent trend in services inflation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 3.3% year over year in May, while services inflation excluding energy services rose 5.3% year over year.

Many observers attribute the “stickiness” of services inflation to rising nominal wages as workers struggle to keep up with inflation. Subduing services inflation would be very socially costly; it would require significant monetary tightening by the Fed, leading to a sharp rise in unemployment. While the Fed is not (yet) willing to go down this path, stubborn services inflation means that US interest rates will have to remain high to achieve the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

But this answer, justified by generations of inflation hawks warning about wage-price spirals, is far too simplistic.

More than a year ago, we analyzed the wave of inflation that hit much of the world. Anticipate the effort Attempts to fix U.S. inflation by raising interest rates will never come close to making it affordable. The most obvious problem is that services inflation is being driven in large part by a surge in consumer spending on restaurants, travel, health care, and other big-ticket services.

Most of this spending is coming from the ultra-rich — wealthy, often older Americans who have benefited from the massive gains in the U.S. housing and stock markets in recent years. Record increases in household wealth have given the wealthy the confidence to increase their spending, which is a key reason why the U.S. economy has defied expectations of a slowdown despite big increases in interest rates. This wealth effect is a key factor in the persistence of services inflation.

Let’s take a closer look at the relevant facts. Fueled by ultra-low interest rates set by the Fed, the average home price in the United States increased by 47% between Q1 2020 and Q1 2024, recently reaching a new record. As a result, the value of householders’ assets in real estate has increased by $13.4 trillion. Stock prices, as measured by the S&P 500 index, are more than 80% higher than they were five years ago, adding trillions of dollars to household wealth. As a result, U.S. household wealth increased by a record $47 trillion between Q1 2020 and Q1 2024, recently peaking again.

The increase in wealth has by no means been universal. The richest 1% of American households captured 30% of this impressive increase in financial assets, and the richest 10% captured 59% of the wealth increase ($21.7 trillion). In contrast, the bottom 50% of the wealth distribution received only 5% of the recent increase in total household wealth. Wealth is also disproportionately held by older people, and of course by white people. People over the age of 55 own almost three-quarters of all household wealth. But many older people face significant financial challenges: one-quarter of Americans over the age of 50 have no savings for retirement (according to a U.S. Department of Labor survey). AARP).

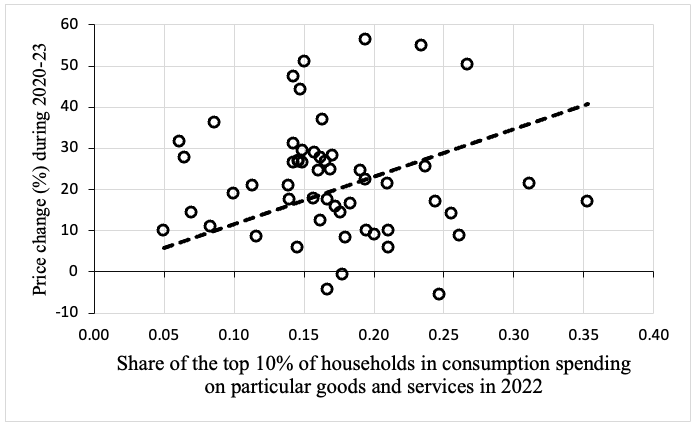

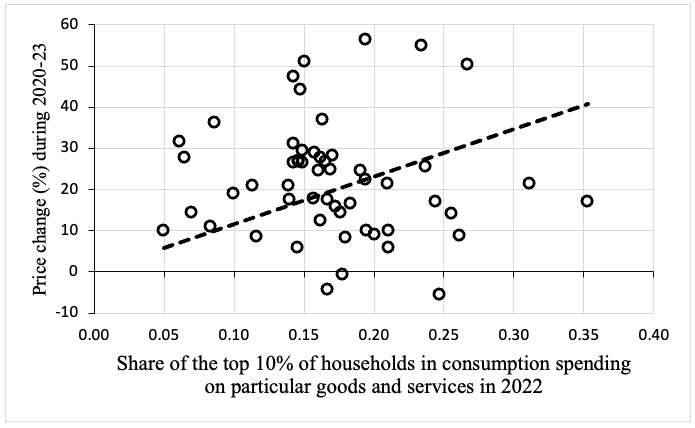

One might reasonably expect that some of this increase in household wealth would affect household consumption, particularly the spending of the wealthiest 1% or 10% of U.S. households, and through that, inflation. Our recent research uses very conservative estimates of the impact of a one-dollar increase in household wealth on consumer spending to estimate the size of that impact. We notice Economists believe that almost all of the recent increase in American consumer spending is due to the wealth effect. Moody Analytics and visa They report that rising household wealth has a similar impact on spending, and supporting our argument, the chart (below) shows that the prices of goods and services purchased by the wealthiest 10% of US households increased significantly from 2020 to 2023.

The Fed’s monetary tightening The Two Sides of the American EconomyMeanwhile, the small number of super-rich Americans who own homes, stocks and cars are relatively immune to rising interest rates: Their spending requires little borrowing, they can provide collateral and thus secure preferential interest rates as they increase their debt, making them relatively immune to the pressures of the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates to slow growth and curb inflation.

The goods and services purchased by the wealthy have become more expensive

Source: Ferguson and Storm (2024).

In contrast, the vast majority of Americans are living with soaring home prices, rising rents, high mortgage interest rates, and (despite widely publicized claims to the contrary) Stagnation (and even decline) of real wagesit is nearly impossible to buy a home unless you already own one. This polarization of the US economy is driven by the growing economic influence of the super-rich, which is rapidly reshaping the structure of the US economy. While fine dining jobs are flourishing, low-wage jobs in nursing homes, child care, education, and more are drying up. The result is not only distributionally regressive, but also patently irrational.

By continuing to maintain high interest rates, the Fed is acting like James Dean in the famous “Chicken Run” auto race. Rebel Without a CauseEmbarrassed by its failure to predict the level of inflation and determined to control inflation expectations, the Fed continues to pursue policies that many analysts perceive as increasingly risky (the technical term is “data-driven,” meaning the Fed is sailing well beyond the Pillars of Hercules).

The problem is that the Fed refuses to acknowledge the connection between the wealth effect, consumer spending by the wealthy, and inflation, so if it continues with its policies it will send the economy off a cliff. Raising interest rates will not fix this problem, except with a Volcker-style tightening of monetary policy so dramatic that it erases the wealth effect. That would almost certainly send the U.S. economy into a major recession, The End of Profound ImpactFor now, the Fed is simply keeping interest rates high and hoping for the best, hoping for some bright spots.

The sad truth is that this policy conundrum was created by the Fed itself. It’s time to take away the keys to this Chicken Run. We can’t rely on the Fed to get the economy out of this mess. Addressing the underlying problems requires fiscal and other policies, including serious efforts to regulate industries like electricity production and transmission in the public interest, not fruitless tightening of interest rates on the rest of the economy.