I’m Yves. In this paper, we show that union membership is beneficial for workers even in times of generally weak labor bargaining power. In this article, we find that the benefits, not just in terms of nominal wage rates but also in terms of total weekly wages, are substantial, even if they are lower than they were 50 years ago.

by David Blanchflower, Bruce V. Rauner Professor of Economics at Dartmouth College, Professor of Economics at the University of Glasgow, and Alex Bryson, Professor of Quantitative Social Science at the Institute of Social Science, University of London. Vox EU

Union membership rates across the developed world have been declining for decades. In this column, we use data on US wages and hours over the past 50 years to examine whether this has led to a decline in the “union wage premium.” The authors find that while the hourly wage premium for union members has fallen significantly since the 1970s, the weekly wage gap remains large, in part because union members work longer hours. This little-explored role of unions is important for the welfare of workers whose consumption depends not only on an adequate hourly wage but also on the provision of sufficient paid work hours.

Across developed countries, union membership has been declining for decades (Garnero et al. 2017): today, union membership in the U.S. public sector is 33%, compared with 6% in the private sector, down from 24% 50 years ago.

This decline signals a shift in bargaining power between employers and workers, which some believe has resulted in a decline in the share of labor income (Summers and Stansbury 2020). Because unions’ ability to bid above-market wages stems from their ability to encourage members to support their bargaining position and, if necessary, to withdraw labor through strikes, one might expect this decline in unionization to have led to a long-term decline in the union wage premium (the margin that unions achieve over the wages of comparable workers in the absence of a union). But has this actually happened? The short answer is no.

To address this question, we examined data on employee wages and hours worked over the past 50 years from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) (Blanchflower and Bryson 2024). Following a long tradition in labor economics dating back to Lewis (1963) in the early 1960s, we compared the unadjusted difference in average hourly wages between union and nonunion members with the adjusted difference, controlling for potential confounding factors such as education.

In 1973, union members earned about two-fifths more per hour than non-union workers (40%), but this was cut in half to 20% by 2023. This “unadjusted gap” was always above 35% except for two years toward the end of the century, but has been below that since then, with a notable decline beginning around 2013-2014, accelerating with the advent of COVID.

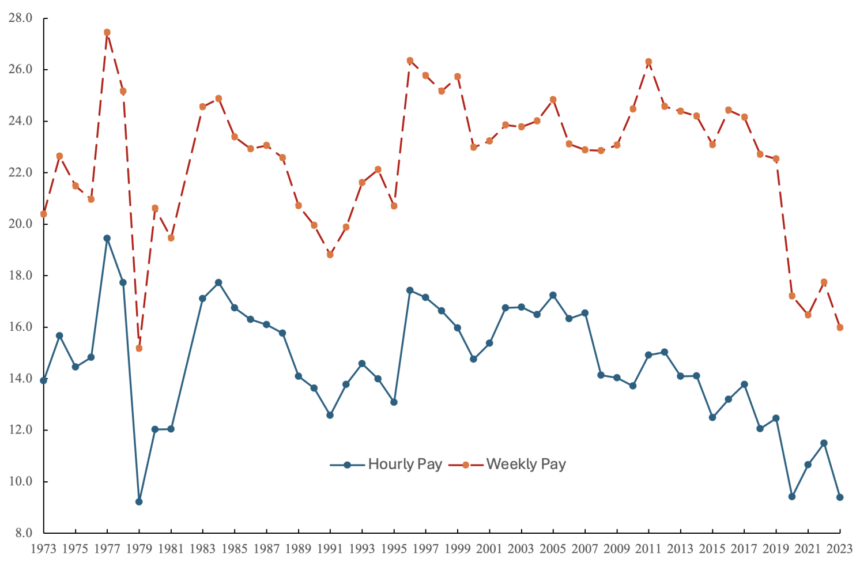

The adjusted union hourly wage premium has been substantially smaller than the pre-adjustment “gap” throughout the 50-year period, rarely exceeding half of the pre-adjustment gap, and has fluctuated between 10% and 20% for most of the period. During COVID-19 it has fallen below 10%, but is still sizable and significant (see the blue line in Figure 1).

What has received little attention in the literature on the union wage premium is the much larger gap between average weekly wages of union and non-union workers. By 2023, the unadjusted weekly wage gap between union and non-union workers was 31%, nearly half what it was 50 years ago. But the adjusted weekly wage gap has been more stable, fluctuating between 20% and 26% from the early 1990s until just before COVID. It has declined during COVID-19, as has the hourly adjusted premium, but it remains at 16% in 2023 (see orange line in Figure 1).

Figure 1 Adjusted union wage premium, 1973-2023, Total US economy, CPS (%)

The large gap in weekly wages between union and nonunion workers is due to the hourly wage premium as well as the fact that union workers work about 5% longer each week than nonunion workers (1-2 hours per week). This is a little-known empirical regularity; indeed, earlier studies incorrectly concluded that nonunion workers work longer hours than union workers (Perloff and Sickles 1982; Earle and Pencavel 1990). The difference in hours worked partly reflects the ability of unions to address underemployment, with union workers working hours closer to their preferred hours than nonunion workers.

It is quite striking that the regression-adjusted difference between weekly and hourly wages has remained stable over a half-century. To be sure, the weekly union wage premium has fallen since COVID-19, and the hourly union wage premium was falling before the pandemic. And yet, both remain large and substantial in 2023.

This trend is not consistent with a world in which unions have completely lost their bargaining power. But these premiums are not driven solely by unions’ collective bargaining power. Other factors may also be at play, such as the “batting average” (Metcalf 1989) effect that results from unions being able to maintain a presence in workplaces where they can share in larger rents. Perhaps most striking is the role that unions play in increasing hours worked. This is a role that has not been clearly demonstrated in the literature so far, but which is crucial for the welfare of workers whose consumption depends not only on an adequate hourly wage but also on the provision of sufficient paid work hours.

look Original Post References