Intro. (Recording date: June 6, 2024.)

Russ Roberts: Today is June 6th, 2024, and my guest is Professor Eugene Kontorovich of the Scalia Law School at George Mason University. His specialties are Constitutional law and international law. Our topic for today is what is sometimes called the West Bank, sometimes called Judea and Samaria, and sometimes called the occupied territories, and sometimes called the Palestinian Territories. Eugene, welcome to EconTalk.

Eugene Kontorovich: Great to be with you Russ.

Russ Roberts: The area we’re talking about, which I’m going to try to call by the somewhat-neutral name, the West Bank, was taken by Israel from Jordan in the Six-Day War in 1967. It is west of the Jordan River. It consists of towns where Arabs live, where Jews live. There are about 450,000 Jews in the West Bank. Another 250,000 live in what’s called East Jerusalem, which is technically a separate area. And, there are about 2.7 million Arabs in the West Bank.

Now, many people describe Israel’s role in the West Bank as an occupation–that Israel’s towns and settlements violate international law. Let’s start with that case. I know it’s not your view, but for the people who consider Israel an occupying power, what is their argument?

Eugene Kontorovich: So, first I think, let’s start even before anybody’s argument and try to understand what an occupation is. Because an occupation is a term of art. That is to say, it’s a technical legal term. It doesn’t just mean a bad situation. It has a very specific meaning, and it is a term within a subset of international law called the international law of war, or international humanitarian law, as it’s also known.

So, an occupation is a very particular situation that arises in an international armed conflict. That is to say, a conflict between two countries–that could not arise in a civil war, for example–in which one country takes over the territory of another country and then begins to actually administer it and sort of serve as the local government. That is to say, not simply holding it on the battlefield, but kind of replaces the prior government as the acting administrating power in that territory.

So, you need a war; you need two countries, an international war; and you need one country to come and replace another country.

One crucial point is not every time a country takes territory that is previously held by another country, in a war, would it be an occupation. That is not automatic.

So, let me give you some examples. Let’s say Ukraine retakes Crimea. Even though it has been held by Russia for a very long time, we wouldn’t say that’s an occupation; and we can explain why.

nother example, in 1974, Morocco invaded and took over the West Bank–pardon–the Western Sahara. And, many, including many European countries don’t refer to it as occupied. Rather they call it disputed territory or administered territory because it failed the two-country ingredient. That is to say, Western Sahara was not previously a country. It was a kind of abandoned Spanish colony. So, you don’t have an international armed conflict, so it would not be occupied. So, there’s some technicalities, and I think Western Sahara clearly illustrates that.

The basic argument of those who say that Israel is occupying the West Bank, which was laid out in position paper–a legal opinion–by Jimmy Carter’s State Department Legal Adviser–a guy named Hansell–wrote a legal opinion in 1977, which sets the basic arguments for the case of occupation.

And, the argument goes like this. In 1967, Jordan held the territory, the West Bank. Israel took over the territory in 1967 and began functioning as the local government. Thus, occupation.

Now, that argument fails to address I think some obvious questions like Jordan was not the sovereign of that territory. That is to say–and we’re going to go into this in a second–but, everybody agrees, or certainly the United States and Western European countries agree that Jordan itself was an occupying power in the West Bank. That was not Jordan’s sovereign territory.

So, the argument–and I think here the argument does a bit of hand waving or skipping inconvenient wrinkles–they say, ‘Well, it was Jordan’s enough.’ It was Jordan’s enough. I don’t know what that means exactly.

Now, crucially, even under the Herbert Hansell opinion, which was written in 1977, Israel would not be considered an occupying power today. Why? Because occupation can only exist in wartime.

So, when he wrote that opinion–there’s actually a sentence in that opinion. It was written in 1977, so you could say things like this safely because you might’ve think they’d never happened. It said, of course, if Israel were to make peace with Jordan, then there’d be no state of war–if there was an actual peace treaty–and so there would be no occupation.

Now, of course, Israel did make peace with Jordan–unconditional peace–in 1994. That would make, under Herbert Hansell’s own opinion, any state of occupation that did exist in 1967–which I think did not exist–but, even in that view, it would be hard to understand how it survives the peace treaty.

And, I’ll give you plenty of examples of that. For example, America occupied Germany into the 1950s. Then it creates a new German government, makes peace with that new German government. And, the fact that there’s hundreds of thousands and millions of American soldiers in West Germany, it doesn’t make it an occupation.

Or take Afghanistan, which America invaded in 2001, 2002, when it set up an Afghan government in I believe 2003, and made a peace treaty with that government. The continued presence of American soldiers who were engaged in constant hostilities for many years, often against the declared desires of the Afghan government, was not an occupation because there was no war between America and Afghanistan.

So, I think they have a problem with the peace treaty and with Oslo.

Russ Roberts: So, let’s go back and flesh out your argument about Jordan not being a sovereign power. It’s fascinating. For people who don’t know the history, I think there’s still some issues to resolve, but it’s an extraordinary reminder of how complicated the situation is.

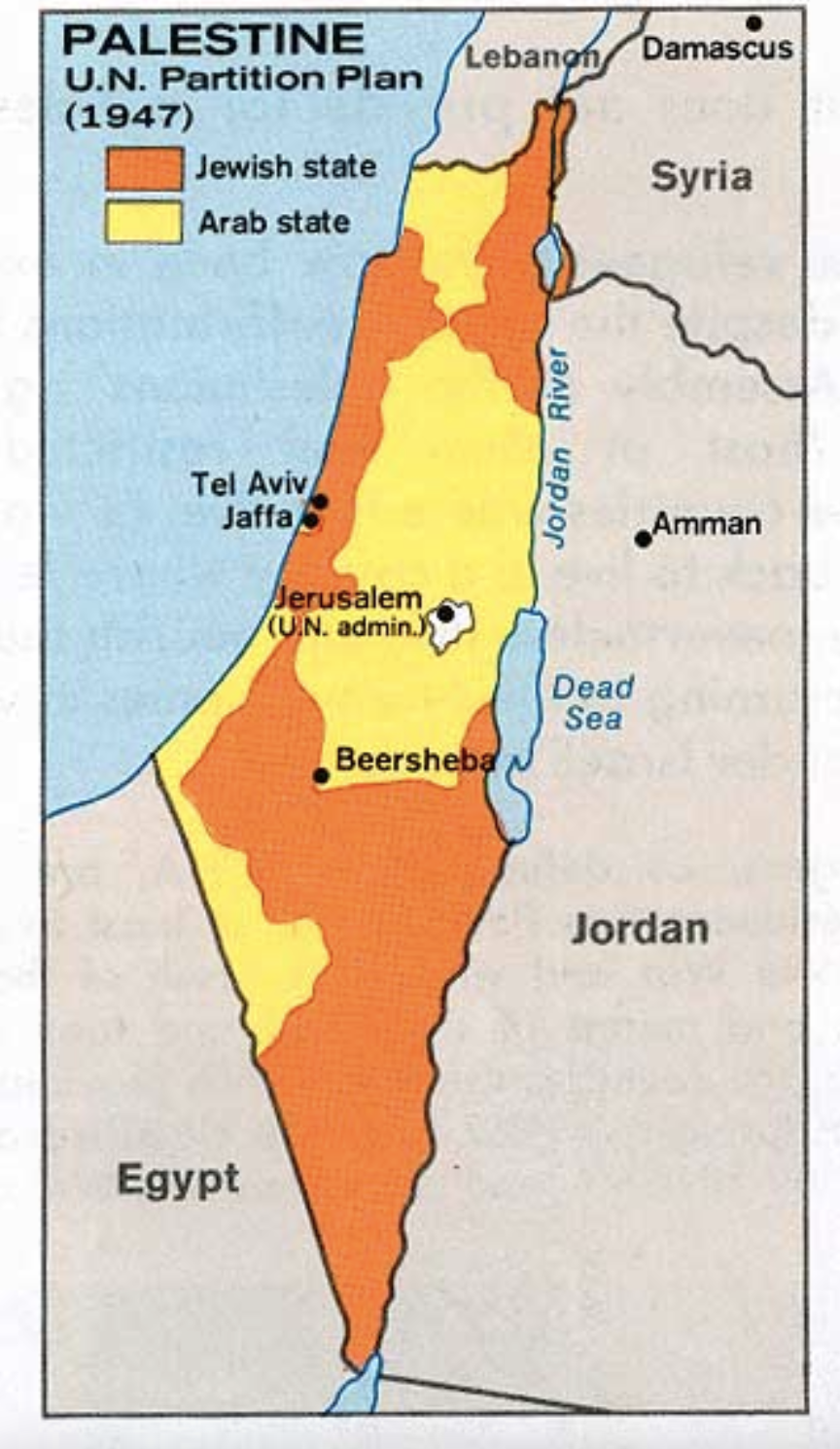

We have to go back another 20 years to 1947, 1948. The UN (United Nations) in 1947 has a partition plan. It’s a very strange partition, but–you look at it, it’s quite bizarre. About 60% goes to Israel, is the proposal; 40% is going to go to the Palestinian people.

But of course, that 60% is misleading. A lot of the land that is that proposed State of Israel is desert. Nobody lives there. Most of the towns in the country and the Palestinian Mandate that had been run by Britain until then are going to fall into the Arab part. And, Jerusalem is going to be an international city. So, it’s 60% Israeli, 40% this new Palestinian country that’s going to be proposed. And, the city of Jerusalem will be international.

Israel accepts the plan with holding its nose, doesn’t like it, but it’s better than nothing. The Arab countries oppose the plan. Israel declares a state and the Arab countries surrounding Israel all invade. What happens next?

Eugene Kontorovich: Okay. So, first of all, the partition plan proposal by the General Assembly in 1947 is often a starting point for these discussions. And, again, I think as a lawyer, my first question is–what they teach you in law school is how to identify the legally relevant facts. There’s always a lot of facts. Which facts are legally relevant?

So, for that partition proposal to be legally relevant it would have to be that the United Nations General Assembly is in the business of making countries and drawing their borders. In fact, it is not. It has never made a country and it has no authority to draw its borders because the United Nations General Assembly is a treaty organization. The only power it has is over its own budget, and all it can do is make recommendations.

And, by the way, they knew that in 1947. If you read the resolution, it is worded as a recommendation to Britain, who was the League of Nations mandatory power; and Britain thought the recommendation was very unwieldy because you mentioned it was a strange map. It actually divides Mandatory Palestine–which was what the entity was then called–into six triangles, kind of. And, the Arabs get three, the Jews get three, and none of the triangles are actually adjacent. Jerusalem and the greater Jerusalem area, including much of Bethlehem, is an international city. Jaffa is a Palestinian enclave, which is now part of Tel Aviv, part of the Arab state. Even the British, which were not excited about a Jewish state, thought that this would be an unworkable solution.

The Jews accepted it because the other option that the UN was considering recommending was no Jewish state. So, the Jews celebrated because this was the less bad of two options in the diplomatic sphere. But it doesn’t have any legal effect.

Now, when Israel declares a State, that is a legally important moment because of international law doctrine called uti possidetis juris. Now, this doctrine may sound obscure, but it is the doctrine in international law that is used to determine borders of new countries.

This is not controversial. You can look it up in an international law encyclopedia. From Africa to Asia, from the International Court of Justice to various arbitral tribunals, this is the rule that is used to determine new countries. And, I think it’s actually interesting to think as an economist maybe to think why it is the rule. We can get to that in a second.

The rule is: when a new country is created–now, it doesn’t say ‘when’ a new country is created. For a country to be created, it has to satisfy various objective conditions. One can have a big dispute about when those are satisfied. For example, there’s such a dispute now about a Palestinian State. There’s such a dispute now about a Somali State, Somali land state, and a Kurdish State. But, generally accepted that Israel met those criteria. It had a territory; it had a government in 1948.

How do you figure out the boundaries of a new country? And, the reason there’s a rule for this in international law is it happens fairly often. So, just to give you an example, there was 50-some countries in the United Nations when it was created. Now there’s 193, with maybe more to come.

So, let’s take an example that is not as ideologically controversial, that is not in the newspapers all the time because I think it’s easier for people to think calmly about things that they’re not emotionally attached to. So take, for example, the former republics of the former Soviet Union (USSR). Take the former Soviet Union. You had a country that was called the Soviet Union.

Now, when the Soviet Union disintegrated, various components of the Soviet Union declared independence. So, how do you figure out the borders of say, Ukraine? Azerbaijan? Armenia? All of whom had border disputes, with Russia primarily?

So, the rule is: When you have a new country emerge from the breakup of a prior country, secession, federal breakup, or even, like, divorce–like in the case of Czech Republic and Slovakia–the country’s borders are the borders of the largest pre-existing administrative unit.

And, to put that just in very simple terms, in America, that would be a state. In Canada that would be–what are they called them? A commonwealth?

Russ Roberts: Provinces.

Eugene Kontorovich: Provinces. In Germany that would be a Länd(?)

And, in the Soviet Union–that would be the Soviet Socialist Republic–there were about 16 of them. They were the top level administrative units.

Now, what does that mean? What that means is you don’t look at a bunch of other factors. History, demography, topography, fairness. Why? Because all of those factors are indetermined. Right? History: where do you go back to? Demography? Demographics never perfectly match political boundaries because groups kind of spill over into different places in different concentrations. Fairness? Who decides fairness?

What recommends this rule is it’s one factor and very simple to administer. You just look.

Now, what this means is often it won’t comport with notions of fairness or demographics because the previous top level administrative unit will often, typically have been drawn by a former colonial power, etc.

Nonetheless, this is the rule.

And let me give you some examples. Take Crimea for example–as Vladimir Putin did in 2014. The international community does not regard that as being rightfully Russia’s.

Now, is it because of this concept we hear often by the Palestinians, self-determination? That the people of Crimea don’t want to be part of Russia? No, the majority of them were ethnically Russian, and they probably did want to be part of Russia. Not 95% or whatever they had in the election that Putin held. That’s just the only number that comes out of Russian ballot machines. But, a majority for sure. And, who knows what the right majority is.

Is it that it was colonial? That it was far away from Russia, like across the seas? No. It was in between Russia and Ukraine, kind of evenly; and Russia certainly has a superior historical claim.

What was the story? Crimea was part of the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic and had been part of the Russian Empire until the 1950s when Nikita Khrushchev, the Secretary General of the Communist Party, redrew the internal maps and gave Crimea to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Did he ask the people there? Was it fair? Was it just? No. Nonetheless, it was very clear that Crimea was in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. And, thus it became, when part of the country Ukraine when Ukraine got independence, rather than the country of Russia.

And, when Russia objected to that, making basically what the Palestinians are making–an ethnic argument–that you should redraw this on ethnic lines, the international community rejected that argument.

And, surely if God were to smile upon the Ukrainians and they were to have some amazing, miraculous military success and retake Crimea from Russia–which doesn’t seem in the cards now, just as it didn’t seem in the cards for Israel for a while to retake the West Bank of Judea and Samaria–I don’t believe anyone in the international community would deem Ukraine an occupier.

Let me restate this all very simply: You cannot occupy territory to which you have a legal claim.

Now, let’s apply that rule, if we may, to the case of Israel in 1948, like you said. Israel declares independence. So, what are its borders? The borders of the last top level administrative unit. What is that? What was called Mandatory Palestine. And that was an entity created by the League of Nations. The League of Nations was, unlike the UN, given power to create mandatory territories out of former Ottoman and German Empire colonies, after the collapse of those empires. And, those were supposed to turn into new independent nation-states.

The boundaries–and Palestine did not mean Palestine in an Arab ethnic sense. It was a purely geographic name for this territory. And, what were the boundaries of that territory? It was what you would call between the river and the sea, or that is to say what we would now call Israel, Gaza, and Judaea and Samaria, as it was actually called by the United Nations at the time, or now what some people would call the West Bank. That was the boundaries.

Every other mandatory country–because Israel was not the only one: Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, places in Africa–inherited exactly the borders of the mandate as it stood at the moment of their independence.

So thus, Israel’s borders at the moment of independence–which is when you apply this rule–would include Judaea and Samaria.

Now, Jordan immediately invades. The invasion was already underway in many ways before Israel declares independence. So, Jordan immediately invades. They make this blitz towards Tel Aviv. Egypt makes a dash along the coast towards Tel Aviv, and the goal of these invading armies–joined by other Arab countries–was to meet in the middle, Molotov-Ribbentrop, and divide the spoils of the country between them.

They partially failed: thus the creation of the state of Israel. Had they succeeded, there would be no state of Israel: No one would say, ‘Oh, UN General Assembly resolution is being violated.’ That would be it. All the Jews would have to be–would be ethnically cleansed.

But, they also partially did succeed. That is to say, Jordan managed to get a certain distance. Egypt got a certain distance. Why is the Gaza Strip known as the Gaza Strip? There’s no natural eastern boundary of the strip. The Egyptian armored columns proceeded up against along the coast. They got a certain distance, they got pushed back a little bit, and that is where they stopped.

Similarly, Jordan went up to the hills of Samaria and Judaea and they were stopped there. That’s why the so-called Armistice Line, which was made at the end of this war, runs through the middle of Jerusalem. That’s not a natural boundary. That’s simply where the Israeli army managed to stop the Jordanian army. So, the entire entity of the West Bank could be redefined. I think a simpler way to put it is the extent of success of Jordanian aggression and conquest in 1948 and 1949.

Russ Roberts: And therefore, your argument is going to be that when Israel in 1967 takes that land back, they’re not occupying it. There are a large group of Palestinians that in a minute we’ll talk about whether that’s outside of the legal question–what does that lead to and how should we think about it?

But, I just want to stop for a second and make the side point–because it’s surprising, I think, for people who are not aware of the history–that between 1948 and 1967, the Gaza Strip was administered by Egypt. They considered it part of Egypt. The world considered it part of Egypt. The West Bank was, quote, “Jordanian.” The world did not agree with your assessment that that land should have been part of Israel. It was considered Jordanian until 1967 when Israel took it back–or took it, depending on your prejudices, interpretations, and so on.

In that time, there were a lot of Palestinians there in the West Bank and in Gaza. And, let’s remind listeners where they came from. In 1948 when Israel declared itself a State right after the British gave up and said, ‘We’re done. We can’t handle this idea of two States. No one seems to like it.’ Israel said, ‘Well, we like it. We’re declaring a State.’

And, the Arab neighbors said, ‘We don’t like it. We’re going to conquer you.’ And as you said, Eugene, they were going to divvy it up. They were not going to create a Palestinian State.

And, when that war broke out, Arab residents of what we would call in 1967–the borders of Israel that many people grew up with, Arabs, some stayed and became Israeli citizens. There’s two million of them. They have complete rights in the modern State of Israel. They go to college, they vote. They don’t have to serve in the army if they don’t want to. Some do, though. They get healthcare. They get all the benefits and blessings and curses of being an Israeli citizen.

So, some stayed. Some fled for their lives, either because the Israeli army was advancing and they were afraid, or because they were told that it was only going to take a little bit of time: the Arab armies would defeat the Zionist entity, and you’ll be able to go back to your homes.

But, my point is, is that those who fled, whether they were pushed out by Israeli military force or they fled out of fear of what was going to happen or because they were encouraged to, many of them settled in the West Bank and in Gaza. And, in the period between 1948-1967 when those areas and those Palestinians were living under the sovereignty of Jordan on the West Bank and Gaza Strip under Egyptian sovereignty, no one said they deserved to stay. At least I don’t remember that. Tell me if I’m wrong.

Eugene Kontorovich: Yeah. You’re mostly right. I just want to quibble with a technical part of the characterization.

Certainly, when Gaza was administered by Egypt and West Bank was administered by Jordan, nobody was saying that they were, a). one entity. That was a claim nobody made, that there was any connection between these two territorial entities separated by the State of Israel in between. Or, that they should be one state or two states.

I would say that there was some difference in the treatment. Egypt never annexed Gaza. Egypt did not. As is the case today, even in 1948 no one really wanted Gaza, and Egypt does not want to incorporate Gaza into Egypt. They administered it under military rule.

Jordan, in 1950, did claim to annex the West Bank, and that’s where the name the West Bank comes from. Jordan named it the West Bank, that is to say the part of Jordan that is west of the Jordan (the Jordan River–Econlib Ed.); because the rest of Jordan has traditionally been known as Transjordan–i.e., on the other side of the Jordan. So, it’s the West Bank in relation to Jordan. That’s a Jordanian name. So, they claimed to annex it. They gave them citizenship. They incorporated.

Only one or two countries in the world recognized the legitimacy of that annexation. That’s an important point.

So, when you say countries treated it as Jordan’s, I completely agree: They didn’t hassle Jordan about it. They weren’t, like, ‘What are you doing in the West Bank? Give it up.’ They completely went along with the Jordanian annexation. But, they made a point to not legally acknowledge it. Much like Turkey is not being really hassled over Northern Cyprus or Morocco is not being hassled extensively over Western Sahara, but they didn’t give it a legal status.

So, yeah, the idea of Palestinian statehood is not really about the Palestinians being occupied–because they were certainly occupied–everybody agrees–from 1948 to 1967 by Jordan and Egypt, respectively. But, that was not thought to warrant a Palestinian state.

Russ Roberts: And now let’s move to a much–I hope we don’t have too much nuance for our listeners so far. It’s going to get a little bit more complicated.

So, I take your point that the legal definition of occupation is hard to apply to Israel, say, over the West Bank either because Jordan really didn’t have it–you could have argued it was Israel’s between 1948 and 1967–or, because Jordan and Israel are now at peace, so who is being occupied? Not Jordanian territory: Only some idea of a potential Palestinian State would have to be the claim.

It’s not really a legal claim. It’s an emotional or moral claim. Which I don’t deny: it’s an interesting, important thing to consider and take seriously.

So, I want to turn to that moral issue. And, I think when critics of Israel today refer to Israel as an occupying state or refer to Israel as an apartheid state, they are talking about the way the Israeli government treats the Arab, Palestinian residents of the West Bank.

So, let’s move to that. And, to understand that which is unbelievably complicated–we will not be able to do justice to it in detail because you need a map and then you need some, too many footnotes.

But, what I want to make listeners aware of is that this area called the West Bank is not a monolith. It has this crazy division that comes from the Oslo Accords of 1993. It has this crazy division between areas A, B, and C.

In addition, they’re not really areas. It’s a bad word. Areas, to me means a geographic contiguous thing, like The West in the United States. That’s an area. It’s the area: You could debate where it is. Is it west of the Rockies? Is it west of the Mississippi River? But, the West is–you wouldn’t want to say there’s some East inside the West. That’s silly.

But areas A, B, and C are like that. So, areas A, B, and C, even though they are called areas, a better way, I would say, to describe it, is there are three different legal regimes under which people in the West Bank live: A, B, and C. Let’s try to let listeners understand the differences between areas A, B, and C. (More to come, 27:38)