Hi, Yves. The AMA played a major role in blocking the introduction of some kind of public health care system, but they were not the only villains. It would be a shame if this account of the AMA’s successful tactics obscures the role of U.S. labor unions. They also opposed government-provided health care. They wanted to make it an important contractual benefit to justify the need for union negotiations, and therefore the need for union dues. However, there are many ways in which labor unions can help workers. We know this from the fact that overseas labor unions did not go bankrupt en masse after European countries introduced government-paid systems. Thus, the union’s actions were particularly disgraceful because they benefited the leadership while not helping the rank and file and hurting the broader American public.

Doctors are paying the price for the terrible deterioration of American health care, not just for patients but for themselves, but the current generation of doctors has not joined the anti-government medical movement, a professional version of the son paying for the sins of the father.

Article by Marcella Alsan, Angelopoulos Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, Yusra Nevelay of the Harvard School of Public Policy, and Xinyu Ye, a doctoral student at Princeton University. Vox EU

The U.S. health care system relies on a heavily subsidized and loosely regulated private sector, leaving millions of Americans uninsured, underinsured, or with unknown insurance coverage, despite living in the world’s wealthiest country. This column examines the rise of private health insurance after World War II, when the American Medical Association, an interest group representing doctors, funded a national campaign against national health insurance. The campaign, directed by America’s first political public relations firm, used mass advertising to associate national health insurance with socialism and private insurance with “the American way.”

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) developed by the United Nations have advanced the goal of achieving universal health coverage (UHC) in all countries by 2030 (Eozenou et al. 2023). This goal has already been achieved in most high-income countries, with a notable exception being the United States. Despite living in the world’s wealthiest country, millions of Americans remain uninsured, underinsured, or unsure if they will be insured (Blumenthal and Collins 2022; Scott 2023a). Medical debt remains the leading cause of personal bankruptcy, and the United States’ performance on several key health outcomes has consistently underperformed comparable countries (Schneider et al. 2021; Kluender et al. 2021; Papanicolas et al. 2018). Recently, prominent health economists have pointed to the U.S. health care system, with its reliance on a heavily subsidized and lightly regulated private sector, as an integral part of the problem (Case and Deaton 2020; Einav and Finkelstein 2023).

In a recent paper (Alsan et al. 2024), we take a step back from this current debate and try to understand how the United States developed its unusual health care system. Typical explanations include a history of individualistic culture, union negotiations, inflationary pressures, and tax benefits for employer-sponsored health insurance (Scott 2023b). We investigate another potential contributing factor: a massive marketing campaign after World War II funded by the American Medical Association (AMA), an interest group representing physicians, in conjunction with other industries. The campaign was run by Whittaker & Baxter’s (WB) Campaigns, the world’s first political public relations firm. The campaign has been discussed before, most famously in New Yorker Whittaker and Baxter’s profile (Lepore 2012 ) – to our knowledge, our paper provides the first rigorous analysis of whether and to what extent interest-group-funded campaigns that relied heavily on indirect lobbying of voters shaped the health insurance landscape at a critical turning point.

The campaign was launched quickly, in response to what the AMA described as an “Armageddon moment.” The reasons for the AMA’s alarm were manifold. First, events abroad, notably the introduction of the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, provided an example of state-sponsored health care in a country that shared a common language and legal traditions. Second, the shock election of Harry Truman in 1948 had put a strong advocate of national health insurance in the White House and a Democratic supermajority in Congress, ensuring that the issue would be on the legislative agenda. Third, Americans were very much in favour of national health insurance, and the main justification for this was said to be concern for the less fortunate.

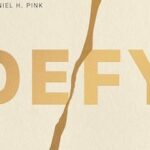

The AMA-WB campaign had two main components. First, it used mass advertising to associate the NHI with socialism and to portray a private (or voluntary) insurance option as the “American Way.” These AMA advertising efforts were complemented by tie-in advertising from other industries that feared a return to wartime price controls. In addition, the strategy called for AMA physicians to discuss private health insurance with their patients and distribute pamphlets that reflected the individualistic advertising message (see Figure 1). Through local and state health organizations, physicians who wanted to reduce the burden of medical costs organized their own insurance products, which became known as Blue Shield and coveted subscribers. In total, about $250 million (in today’s value) was spent to mobilize voters, an unprecedented amount at the time. Physicians were also instructed to use their fame to urge local civic organizations to pass resolutions opposing national health insurance.

Figure 1 Campaign Brochure

NoteThe figure shows two examples of pamphlets distributed by AMA-affiliated physicians during the campaign.

sauceIn: Whitaker and Baxter Campaigns, Inc. Archive.

We reconstruct the strength of the AMA-WB campaign using multiple newly digitized data sources, including Campaigns Inc. archival information, the AMA’s digitized medical directory, the American Hospital Association (AHA) hospital directory, billings from advertising firm Lockwood-Shackelford, and newspaper directories. The strategy outlined in the campaign documents did not target specific locations because they had to react quickly and modern statistical methods of market analysis had not yet been developed. Furthermore, because health insurance was a new product, the market was far from saturated. Instead, Campaigns Inc. relied on existing relationships and resources, such as leveraging advertising firms it had used for years and promoting the sale of private insurance through AMA members. Empirically, we find that campaign exposure was not correlated with existing (low) private health insurance levels, conditional on factors that may affect the demand for private health insurance products, such as income, unions, and hospitals. Our primary interests are private health insurance enrollment digitized from newly discovered Blue Shield reports and public opinion data from Gallup polls. Our analysis ends with 1954, the year the federal government classified health insurance payments as tax-exempt and companies began to compete aggressively with Blue Shield.

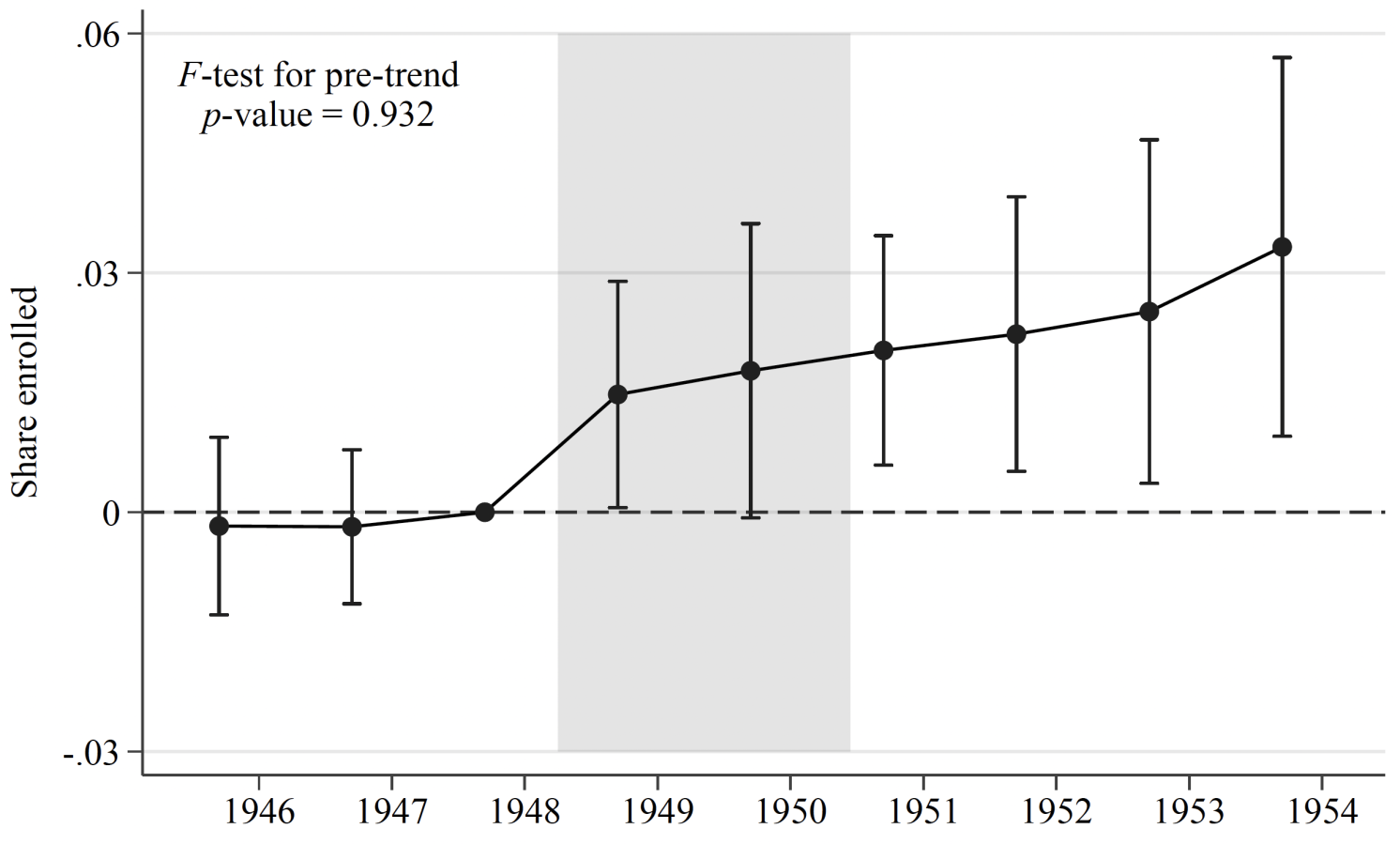

We find that a one standard deviation increase in exposure to the AMA-WB campaign explains 20% of the increase in private health insurance enrollment during this period (Figure 2). And public support for legislation to establish national health insurance declined similarly. While the results on public opinion are remarkably similar across a wide range of individual characteristics, respondents who voted Republican in the previous election appear to be more influenced by the campaign, perhaps indicating that the ideological framework appealed to members of that party. We also find evidence to suggest that the campaign changed the narrative of how lawmakers described the proposed health insurance bill, using descriptions such as “mandate” instead of “state” in passages quoted from the Congressional Record. The influence of the campaign was also seen in the wording of Gallup poll questions, and continued until national health insurance was no longer asked after it had fallen off the legislative agenda. Taken together, our findings provide evidence of underappreciated factors in why the United States has developed a unique and complex health care environment. Although a historic paper, these findings may take on new importance given recent evidence on the importance of health insurance in increasing labor productivity, reducing health disparities, and reducing mortality rates (Baten et al. 2023; Del Valle 2015; Miller et al. 2021; Goldin et al. 2021).

Figure 2 The effect of the campaign on private health insurance enrollment

NoteThe figure shows the event study coefficients of campaign exposure on private health insurance enrollment from 1946 to 1954. For more details, see Alsan et al. (2024) .

But why did the United States not subsequently change course? In this paper, although data limitations prevent us from easily arguing for empirical persistence, we offer several reasons why the case for national health insurance weakened substantially after the AMA-WB campaign. First, as middle-class Americans increasingly purchased private insurance for themselves and eventually their dependents, the public option became less personally useful to many voters. In fact, according to campaign documents, this was the explicit intention of offering a private option in the first place. Second, for-profit insurance companies have increasingly entered the health industry. Alongside pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, and specialist physicians, these groups continue to derive economic benefits from the status quo, thus blocking any departure from it (Acemoglu et al. 2021). Third, the ideological argument that state involvement in health care necessarily leads to socialism remains common in the United States, and whenever reforms are proposed, opponents’ responses often explicitly refer to fears of socialism (see, for example, Gruber 2011). In other words, the narrative developed and promoted by the AMA-WB campaign is firmly entrenched in U.S. policy debates, with implications for the health of the country and the stability of insurance markets (Krugman 2021; Bursztyn et al. 2020).

look Original Post References