Authors: Alex Hollingsworth, Associate Professor, Ohio State University; Christoph Karbonic, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Emory University; Melissa A. Thomasson, Professor of Economics, University of Miami; Anthony Ray, Associate Professor, University of Southern Denmark. Originally published on VoxEU.

Although infant mortality rates for both black and white infants have declined in the United States over the past century, racial inequalities in infant mortality remain stark. This column focuses on racial inequalities and explores the impact of massive hospital modernization programs in the 20th century on medical capacity and mortality. Improved medical care reduced infant mortality rates and narrowed the gap between black and white infant mortality rates by a factor of four. Cost-effective investments in health infrastructure disproportionately benefited historically marginalized groups, provided long-term benefits, and complemented rather than replaced medical innovations.

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “(e)Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family, including health care and necessary social services” (United Nations 1948). Yet much of the world’s population lacks access to doctors and hospital care. In 2017, North America had 2.7 hospital beds per 1,000 people, while South Asia had just 0.6 (WHO 2017).

Access varies among high-income countries. The United States and Switzerland have the world’s highest per capita health care expenditures, yet the United States has 60% of the hospital beds and physicians per 1,000 people as Switzerland (Papanicolas et al. 2018; WHO 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic (Propper and Kunz 2020), combined with trends in centralization of care, physician shortages, and underfunding, may further limit access and create medical deserts, especially in socioeconomically and racially disadvantaged areas. Studies of the impact of hospital capacity reductions are mixed. Kozhimannil et al. (2018), Germack et al. (2019), and Gujral (2020) report negative effects of hospital closures, while Fischer et al. (2024) did not find similar results.

In the United States, these challenges remain despite dramatic changes in health care spending and population health over the past century (Cutler et al. 2019). Over the past century, health care spending has increased tenfold, infant mortality rates have fallen by 95%, and life expectancy has increased by 45% (Costa 2015). However, these impressive gains have not been equal across racial groups (Muller et al. 2019). In 1916, infant mortality rates per 1,000 live births were 184.9 for black infants and 99.0 for white infants, a ratio of 1.9 (Singh and Yu 2019). By 2021, Black and White infant mortality rates had fallen to 10.6 and 4.4, respectively, but the gap had widened to a ratio of 2.4 (Ely and Driscoll 2023).Thus, despite a significant decline in overall mortality, racial inequality in infant mortality is worse than it was at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Given the twin realities of unequal access to health care and racial inequities in health outcomes, it is essential to understand whether investments in health infrastructure can mitigate these deficiencies, especially given that health care now plays a central role in modern society, accounting for approximately 20% of U.S. economic activity.

The Duke Foundation’s modernization campaign and its impact on the hospital sector

In a new paper (Hollingsworth et al. 2024), we study how funding for health infrastructure affects medical capacity and mortality, with a particular focus on racial inequality. Our study is based on a unique quasi-experiment: a large-scale hospital modernization program supported by the Duke Foundation in North Carolina in the first half of the 20th century. The philanthropic foundation helped hospitals expand and improve existing facilities, acquire cutting-edge medical technology, and improve management practices. In certain communities, it also helped build new hospitals or convert existing facilities to nonprofit status. Although funding only began in 1927, by the end of 1942 the foundation had allocated more than $53 million (in 2017 dollars) to the state.

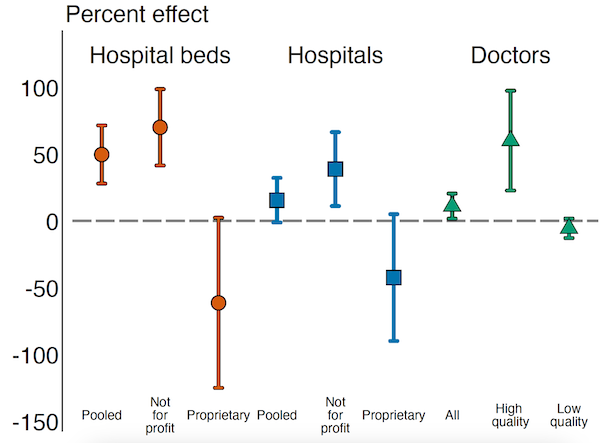

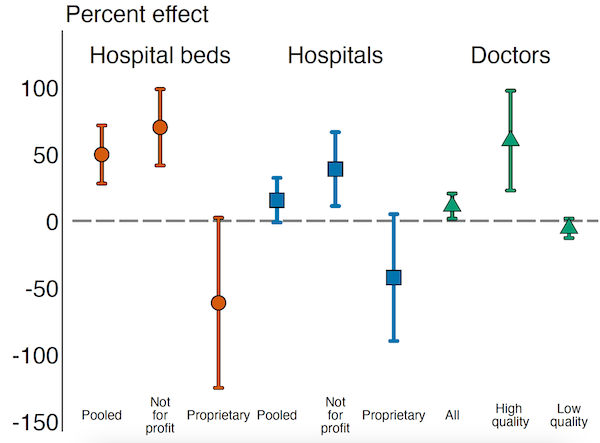

The funding increased the number of funded nonprofit hospitals per 1,000 births while decreasing the number of unfunded for-profit hospitals (Figure 1). This substitution effect was also reflected in the number of hospital beds, which increased by 70.1% for nonprofit beds while decreasing by 61.4% for for-profit beds. This resulted in an overall increase in both the number of facilities and the number of hospital beds. Furthermore, supported areas saw a 60.2% increase in quality physicians per 1,000 births, a 5.5% decrease in poorly trained physicians, and an improvement in average medical knowledge in the areas supported by the fund (Figure 1). These effects persisted for more than 30 years, suggesting a durable increase in capacity.

Figure 1

Impact on infant mortality and long-term mortality

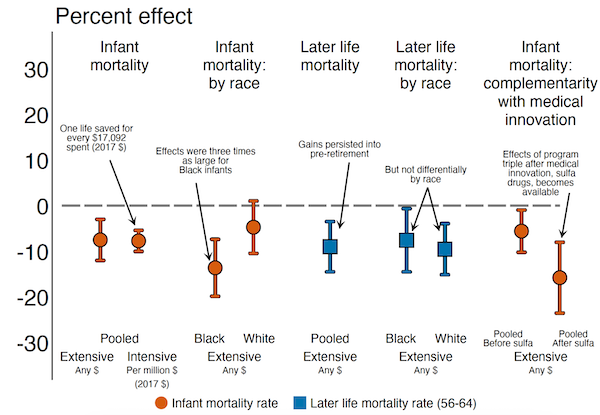

Changes in health infrastructure help explain our key finding that Duke funding improved the health of these communities, reducing infant mortality by 7.5% (Figure 2). The increase for black infants (13.6%) was nearly three times that of white infants (4.7%), narrowing the mortality gap between black and white infants by a quarter. Moreover, those who received support at birth also enjoyed lasting health benefits, with a 9.0% reduction in long-term mortality (ages 56 to 64), a benefit that accrued to both races equally. These investments were cost-effective: one life was saved for every $17,092 (in 2017 dollars) paid to hospitals, a cost significantly lower than any reasonable estimate of the statistical value of a life.

Figure 2

Complementarity between capital investment and medical innovation

Finally, we show that Duke-supported hospitals made more effective use of new medical advances, suggesting a complementary relationship between high-quality hospitals and new medical interventions (Figure 2). We explore this by estimating an interaction between Duke support and the discovery in 1937 of a sulfa drug that effectively treated pneumonia. In regions with a low baseline pneumonia mortality, we find no effect of Duke funding. In contrast, in regions with a high baseline pneumonia mortality, we see benefits both before and after the medical discovery, with the effect being nearly three times larger in the post-antibiotic era. This reflects the complementary nature of hospital modernization and medical innovation, and in this case may be explained by the fact that funding attracted more qualified physicians to the region, who were able to make better use of new technologies.

Conclusion

We conclude that investments in health infrastructure (1) lead to durable improvements in the supply and quality of health care available to affected populations, (2) have short- and long-term mortality reduction effects, (3) disproportionately benefit historically marginalized groups, (4) complement rather than substitute for health care innovations, and (5) are cost-effective, at least in settings with low initial levels of health care provision, as remains the case in many low-income countries today.