Should we desire the greatest good for the greatest number of people? (By the way, does “we” mean the numerical majority?) The trolley problem in philosophy raises this question. I was reminded of it in an interesting article by economist and philosopher Michael Munger:Adam Smith discovered (and solved!) the trolley problem” (June 28, 2023) and sequels Econtalk Podcast.

The precise form of the Trolley Problem was formulated by British philosopher Philippa Foot in a 1967 paper: Imagine a runaway trolley hurtling down a steep hill, threatening to strike and kill five men working on a railroad track. However, you are near a switch that can divert the trolley onto another track, where only one man is working, and none of the men see the trolley coming. If you switch tracks, you are sure that only one man will die, not five. Should you switch tracks, as the utilitarian would have done?

If you answered yes, consider the equivalent dilemma (taken from Munger’s article):

Five patients in a hospital will die tomorrow unless they receive (a) a heart transplant, (b) a liver transplant, (c) and (d) a kidney transplant, and (e) a transfusion of a rare blood type. The hospital also has a sixth patient who, by amazing coincidence, is an exact match to be a donor for all five of them. If the head surgeon does nothing, all five will die tonight with no hope of living until tomorrow.

Assuming there are no legal risks (the government is run by utilitarians who want the greatest good for the greatest number of people and who like cost-benefit analysis), should the chief surgeon kill the organ donor and remove his organs to save five lives? To answer this question, most people would probably change their minds and reject the crude utilitarianism we endorsed in the trolley problem above. Why?

Munger argues that Adam Smith formulated another example of the trolley problem in his 1859 book. Theory of moral sentiments And he discovered a principle that solves it. Although Smith didn’t put it that way, his solution illustrates the difference between intentionally killing an innocent person, which is clearly immoral, and letting that person die from independent causes, which are not necessarily immoral. Drowning someone in order to kill him is immoral, but not saving a drowning person may not be. Intentionally shooting an African child is murder, but not donating $100 to charity that would have saved his life is certainly not a crime.

A recent discussion by Philippa Foot (see chapter 5 of her book) Moral Dilemmas: Other Topics in Moral Philosophy (Oxford University Press, 2002) explains that the fundamental underlying difference is “between causing a harmful chain of events and not intervening to prevent it.” (Here’s a succinct representation of her entire argument from the abstract of her paper.) More precisely, she writes:

The question of our concern is dramatically raised by asking whether we are as responsible for allowing people in Third World countries to starve to death as we are for killing them by sending them poisoned food.

The basic principle that emphasizes moral conduct is

While it is sometimes permissible to allow some harm to befall someone, it is wrong to bring that harm upon that person by one’s own actions, that is, by starting or continuing a series of actions that bring about the harm.

In his 2021 book Knowledge, reality and valuesLibertarian anarchist philosopher Michael Huemer has also considered the trolley problem and arrived at a similar, though more subtle, solution to the extreme case. His philosophical approach is “intuitionist”, as the subtitle of this book suggests. An almost common sense guide to philosophy(My double Regulation review, “A broad-minded libertarian philosopher, rational and radical” is a book and his The issue of political power: examining the right to enforce and the obligation to obey (2013).

Anthony de Jasay’s attack on utilitarianism as a justification for government (coercive) intervention is based on the simple economic observation that there is no scientific basis for comparing utility between individuals. For example, it is nonsensical to say that saving five people leaves “more utility” than killing one. He writes that utility statements are “unfalsifiable and will forever remain my argument versus your argument.” ( My Econlib review of him Against politics.)

What is pretty certain is that utilitarianism, and of course “act utilitarianism” (as opposed to “rule utilitarianism”), does not work except in perhaps the most extreme and uninteresting cases. For example, “stealing $20 from Elon Musk without him noticing and giving the money to a homeless person creates net utility”, i.e. the utility Musk loses is less than the utility the poor person gains. Even if this statement seems reasonable, we cannot predict individual actions, only general sequences of events. Perhaps the homeless person will use the $20 to buy cheap booze, get drunk, and kill a mother and her baby who would have been the second Beethoven. He may even be a utility monster, deriving “more utility” from the harm he causes others than from what he loses. Even if the homeless person uses the $20 to buy a used book by John Hicks, Theory of Economic HistoryThen word of his “gift” will spread and a greedy billionaire might clamor for a similar transfer from Musk, or they might campaign for the state to directly confiscate the $20 billion that goes into funding the subsidy.

**************************************************

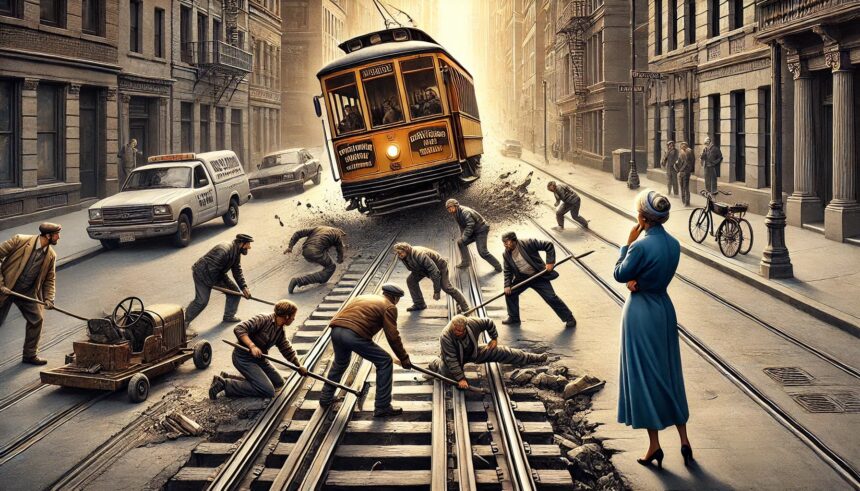

I tried really hard to get DALL-E (the latest version) to render the simplest version of Philippa Foot’s Trolley Problem. Despite my detailed explanations, “he” just couldn’t get it. After all, this isn’t all that surprising. He couldn’t even render the idea of a minecart track with a fork in it, with five workers on one side and one on the other. I finally asked him to draw a runaway minecart with one track and five workers in the middle of the track. The image he produced was one of his most surreal, as you can see from the featured image in this post. Because of his poor performance, I mentally apologized to Philippa Foot (who died in 2010 at age 90) and instructed DALL-E to add to the image “an old, dignified woman (philosopher Philippa Foot) lost in thought, gazing at a minecart approaching.” In this simple task, the robot did very well.

Philippa Foot wonders how DALL-E managed to screw up the trolley problem so badly.