In this episodeHost Russ Roberts welcomes Zvi Mowshowitz to discuss the benefits of AI, reasons for optimism and concern, AI as a “system man,” and technology as the last bastion of freedom to innovate.

Artificial intelligence is still in its infancy, but it is learning to walk quickly. What was once just a chatbot is now The generative AI revolutionis redefining how we communicate, learn, and do business, and it’s just getting started. AI is steadily getting smarter, but what does “smart” mean? In this episode, Mowshowitz points out that Google isn’t “smart,” it just has much more access to information, so is generative AI different? Mowshowitz says yes, but it’s complicated. In general, “smart” means a high level of understanding, problem-solving, and ingenuity. For some questions, chatbots certainly show understanding, but Mowshowitz clarifies that it also has a lot to do with how you ask the questions. Roberts adds that he’s not sure if chat GPTs can come up with a metaphor that will change people’s worldview and bring about powerful intellectual creativity.

Mowshowitz is a short-term optimist. He dismisses fears of job destruction and argues that there are plenty of jobs waiting to be done beneath the surface. But he makes a distinction: short termBut there are still visible concerns, including misinformation and confusion about deepfakes, and longer-term ontological questions that call into question our successful partnership with AI. One such question has to do with creative intelligence itself: How should AI be sustained? Is it even possible?

Meanwhile, a key point of AI optimism lies in signs of progress. Progress DialAs Mowshowitz outlined on Substack: Don’t worry about the vase, It’s a metaphorical dial that represents a collective decision as to whether society allows individuals the freedom to innovate and take risks, or requires them to give permission and observe progress. In Mowshowitz’s eyes, AI is one of the few places where the dial can be turned up a notch. Mowshowitz sees the threat of bureaucracy shackling future innovators across industries, which has led to a concentration of people on AI, cryptography, and CIS in general. In a sense, AI is innovationingenuity, chaotic dynamism, and the potential for rapid progress.

… Over the years, we’ve gone from an America where we’ve had this mentality of, ‘You can go out there, in a wide open field, and do more or less anything you want, as long as it’s not damaging to other people or other people’s property,’ to a world where so much of our economic system requires detailed permission, is subject to very detailed regulation, and makes it very hard to innovate and improve. And I strongly agree with Mr. Andreessen and Mr. Cohen and you and so many others, this is holding us back so much. We’ve been poorer because of this. This has hurt us so much. And we’d be much better off if we loosened the reins.”

But Mowshowitz is not a long-term AI optimist. On the contrary, he argues that many optimistic models lack gears and are too simplistic. For Mowshowitz, these models lack structure, consistency, and logical succession. Not enough time is spent exploring the inner workings of the world within the models.

“When you have AI in your brain, everything becomes a metaphor for a problem in some way. Marx wrote this epic passage about how capitalism is terrible and we’re going to overthrow it and create a communist utopia. And then he wrote five totally vague pages about what a communist utopia would look like. There are a lot of other people who do the same thing. AI is one example, where a lot of people say, ‘We’re going to build this amazing AI system with all sorts of capabilities and we’re going to have a brave new world where everything is great for humans and we can live amazing lives.’ And then they spend a paragraph trying to explain, ‘What are the dynamics of that world?’ Like, what are the incentives, why is this system in equilibrium, why do humans survive in the long run given the incentives inherent in all the dynamics?”

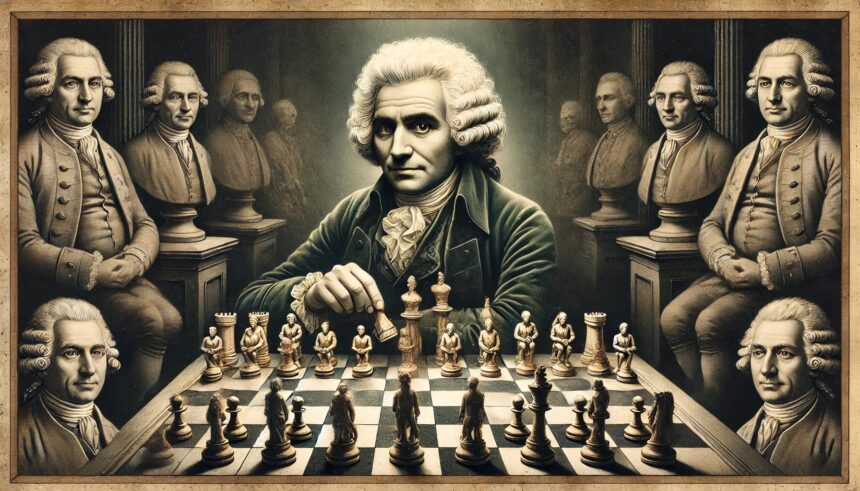

Roberts adds to the pessimism by disputing the argument that AI will run wild. He suggests that AI embodies the goals of developers, regulators and users. In his words, self-driving cars don’t have ambitions, but rather humans are the concern. Use AI perpetuates harm. And he Adam Smith’s System ManThe Systems Man believes he can solve society’s problems by controlling individuals as if they were pieces on a chessboard. But what he doesn’t understand is that the pieces all move according to their own principles of motion, entirely separate from the Systems Man’s will. Roberts believes that AI faces the same problem. There is a clear limitation to AI’s ability to affect the world through control: information scarcity, especially when it comes to the subjective information in an individual’s mind.

Mowshowitz goes on to say that systems humans are humans with limited abilities to access, store, process and use information. AI doesn’t have the same limitations.

“You have to ask yourself: ‘So what is wrong with the systems man in any important sense?’ The systems man has very limited computational power. In any important sense. Right? This systems man is a human being. He can only understand very complex systems, and even though he has all the data in the world in front of him, he can’t actually make meaningful use of much of it… And he’s trying to be the one person directing all of this. He has a hopeless task ahead of him. He will fail… But when we talk about AI, we don’t necessarily have to think about the big picture…”

The vein that connects the Dial of Progress and System People’s consistent failure is the separation of the individual. There is no form of collective knowledge that System People can access; it exists only in the minds of individual individuals. For this reason, progress thrives when individuals who are most informed about their particular strengths and preferences are allowed to pursue their own vision for their lives. System People, who try to impose their vision of progress on the rest of society, fail to understand that individuals are ends in themselves, not means to a unilaterally determined view of social welfare.

But this doesn’t mean that shifting the direction of progress toward asking permission to innovate isn’t harmful. Separation ensures that humans in the system are doomed to fail in the pursuit of their own goals, but Own By fixing the rules of the game, the objectives of individuals, treated as chess pieces, can easily be sacrificed on the altar of nationalism, corporate monopolies, and power-grabbing. AI has the potential to push the dial up, but systems humans could use the same technology to stifle further innovation and human freedom altogether.

Related EconTalk episodes:

Eliezer Yudkowsky talks about the dangers of AI

Nick Bostrom on Superintelligence

Eric Hoel on the threat AI poses to humanity

Dan Klein’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Episode 6

Michael Munger on Innovation Without Permission

Related LF Network content:

Katherine Mungwardt on AI: Reality, Concerns, and OptimismThe Great Antidote Podcast

Harari and the Dangers of Artificial Intelligenceby Pierre Lemieux, Econlib

Accelerating artificial intelligence, not restricting itLaw and Liberty, by John O. McGinnis

Neoliberal Trials: Artificial Intelligence and Existential Riskby Walter Donway, Econlib

ChatGPT and economic planningby Pierre Lemieux, Econlib