This is Eve. Richard Murphy takes some examples from recent financial market panics and argues that most secondary market trading is socially unproductive, therefore it amounts to rentierism and should be suppressed.

There is plenty of evidence to support Murphy’s argument. Studies by the IMF and others have shown that excessively large secondary market trading activity tends to reduce growth. And “excessively large” is not that large. The IMF concluded in 2015 that Poland represents an optimal level of financial “deepening,” which is roughly the difference between the levels of financial and real economy activity. To quote from our post on this article:

As the world struggles with slow growth after the financial crisis and developed countries are still plagued by excess credit and bloated financial services sectors, it has become acceptable, even among serious economists, to question the logic that an expansion of the financial sector is necessarily good. Of course, the logic of “more finance” was never stated in those terms. It was presented under the incantation of “financial deepening” — that is, in layman’s terms, that there are benefits to expanding access to a greater variety of financial products and services. For example, an argument often given in favor of stronger financial services is that it allows consumers to “smooth out expenses over their lifetime.” This basically means that when times are bad or when individuals need to make big investments, they can borrow against their future income. But we already know how well that works in practice. Most people tend to be optimistic, so they tend to underestimate how long it will take to get back to their previous income levels, and even when it does happen, they tend to justify the debt instead of immediately embarking on significant savings. And we have dramatically seen how college debt advocates push students into debt as an “investment” in their education, but never get a return.

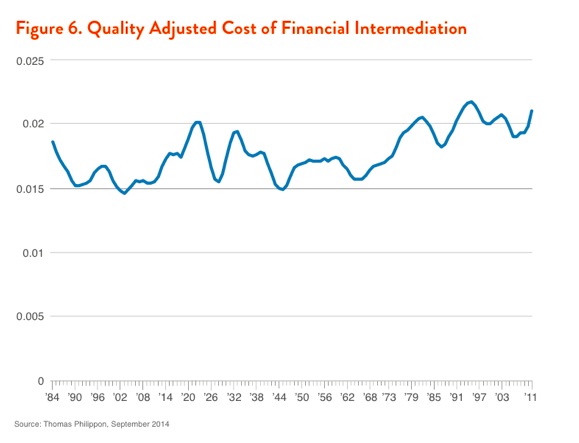

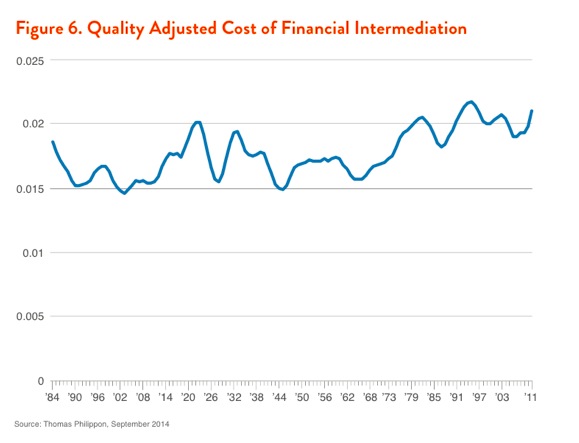

Moreover, despite a significant increase in financial activity and widespread use of technology, the costs of financial intermediation have increased; As Walter Turbewille shows,Citing the work of Thomas Philippon, he states:

However, a recent IMF paper states: Rethinking Financial Deepening: Stability and Growth in Emerging Marketsis particularly deadly. Although the paper focuses on the impact of financial development on emerging market growth, the authors clearly viewed their findings as relevant for developed economies. Their conclusion was that the growth benefits of financial deepening are positive only up to a certain level, beyond which deepening becomes a drag. But what is most surprising about the IMF paper is that the growth benefits of more complex and extensive banking systems peak at relatively low levels of size and sophistication. I encourage you to read the full paper, which is embedded at the end of this article.

The fund argued that strict regulation would probably make more of it harmless, but it’s a completely outdated practice.

Another striking fact is that asset managers are twice as likely to become billionaires as members of the technology industry.

There is an easy way to mitigate this problem: a transaction tax. But aside from the fact that this would embarrass the very wealthy and incur the ire of the politically powerful financial services industry, it would also be an admission of regulatory failure. For example, the SEC has been working hard since the 1970s to lower trading costs and believes that increased liquidity is always a good thing. The regulators should know better by now, but they are too focused on preserving their gains.

By Richard Murphy, Adjunct Professor of Accounting Practice at the School of Management, University of Sheffield, Director of the Corporate Accountability Network, Member of Finance for the Future LLP, and Director of Tax Research LLP. Originally published in Funding the Future

So while the crash in Japanese stocks earlier this week reverberated around the world, it was all panic-induced and had no real impact. Markets have mostly recovered. No doubt some people made a lot of money from the short-term chaos that ensued. And now we must move forward as if nothing happened.

But it turned out to be true: Japan’s stock market revealed just how exposed it was to the risks the Bank of Japan could create in the market by raising interest rates.

The U.S. market demonstrated how vulnerable it was to transactions funded with yen-denominated debt.

It signaled the possibility of panic in other markets as well.

This doesn’t mean we need to move on. Rather, it requires us to recognize how vulnerable the world is to the absurd consequences of permissible decisions by central banks and other institutions. That vulnerability arises because some in financial markets make the inappropriate assumption that they can act as if there is no risk of change, when the risk of change does exist. As a result, they are building on false assumptions.

We saw this with the disaster caused by the Bank of England announcing £80 billion of quantitative easing in September 2022. This disaster panicked markets that had built so-called LDI trades on the assumption that such things would not happen as announced. The resulting panic caused the truss to collapse. That may not have been a bad thing, but it obscured what actually happened, which required significant bank intervention.

This time, that doesn’t seem to have been necessary: markets have decided they can manage the consequences of the changes in Japan’s carry trade.

But my point is that irrational market trading, undertaken purely for speculative gain, without consideration for the intended use of the assets being traded, can have real consequences.

The question is, why do we allow such a totally unnecessary trade to exist when there is no real benefit to society?

I am not against capital markets per se. I acknowledge that they play a role. I acknowledge that the way securities are issued and redeemed means that limited transactions are necessary to provide liquidity for second-hand asset transactions. However, the vast majority of transactions in the vast majority of financial markets are not conducted to provide funds related to productive activities. They exist to extract speculative profits, which in my opinion are a burden on society as a whole, a huge waste of energy, resources and talent for no net benefit, and create considerable risks for society as a whole.

That’s this week’s lesson.

It will be forgotten.