The Financial Times provided some useful coverage in a new front page. 40% of Biden’s major IRA manufacturing projects postponed or pausedBut without context, it’s hard to know what the “results” of this analysis are: are the numbers good, bad, or as expected?

We’ll get to the meat of our findings later, but some unanswered questions include:

What were your expectations for timing and completion? Did you fully allow for the usual initial delays?

How do these results compare to similar non-government manufacturing efforts in these specific industries?

How many of these projects (especially the successful ones) were ones that the company had planned to do anyway? This is a common risk with subsidies and incentives – companies often end up paying for things that were going to be done anyway.

In other words, without a standard of comparison, it’s difficult to know what these findings mean.

Admittedly, it would have been a huge undertaking for the Pink Paper to come up with solid answers given the many industries and projects, but it could have at least acknowledged the need for proper benchmarking and obtained citations from experts.

Separately, it is interesting that the Financial Times published this article as a criticism of the administration. The Financial Times, like other mainstream media, has been firmly committed to the anti-Trump camp. Does this article reflect the Financial Times’s staunch allegiance to neoliberalism? Command Principle Should it be doubted and undermined when it shows its ugly face?

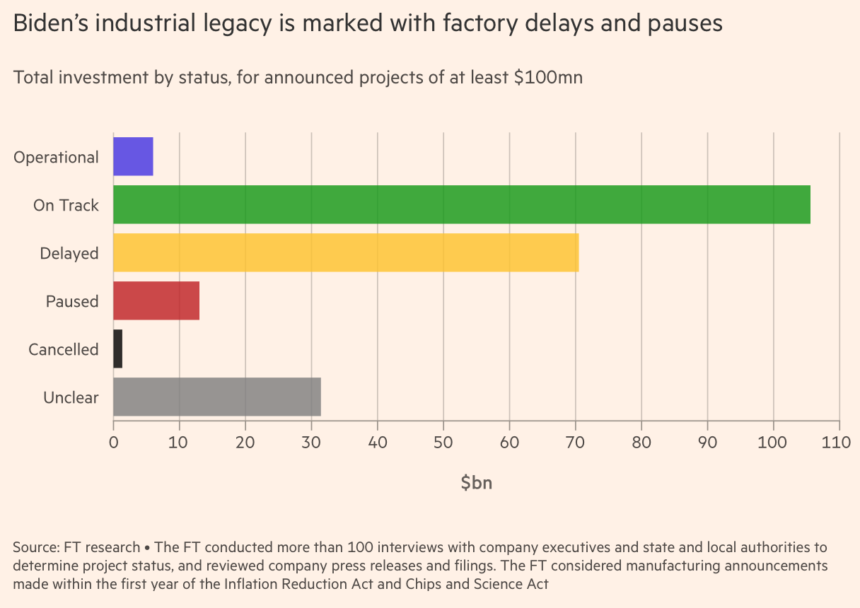

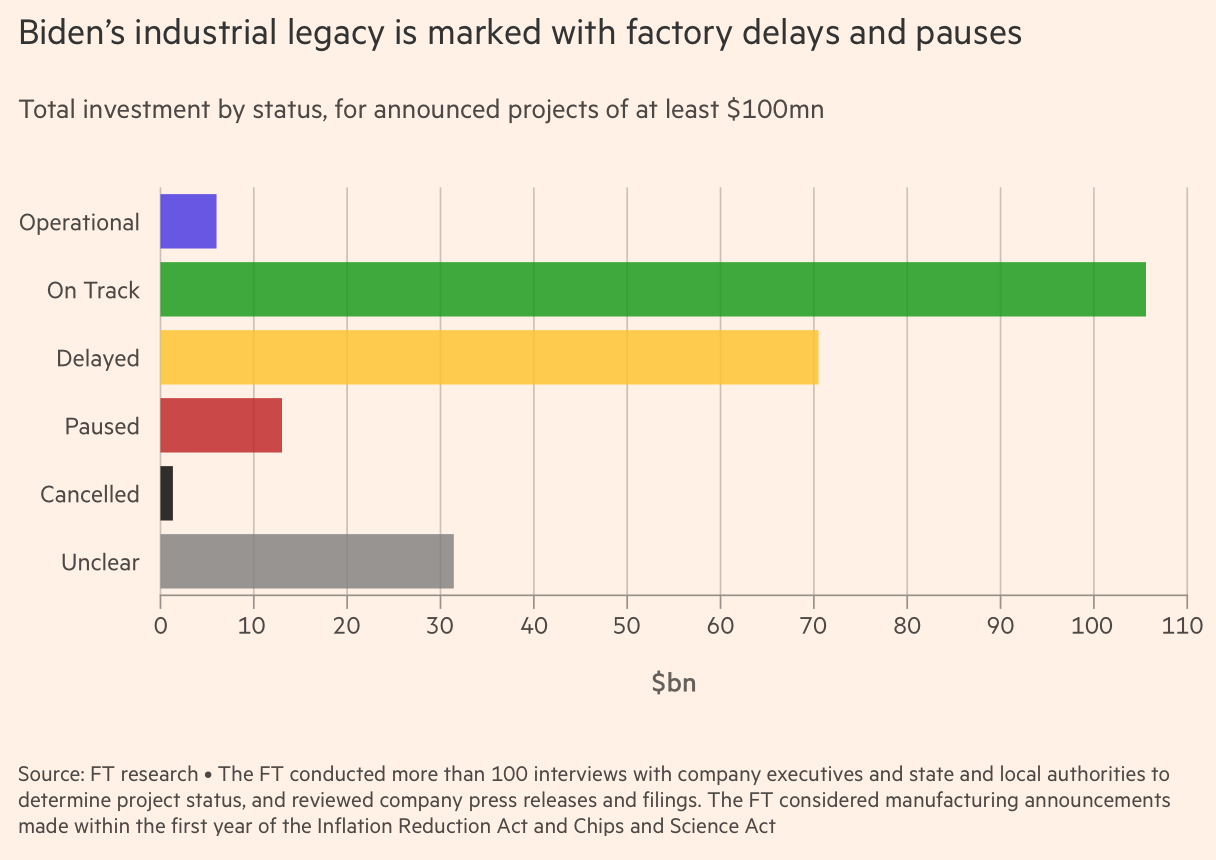

Data summary:

The authors also conducted over 100 interviews with companies and state and local officials, an analytically sound approach that helps understand the results. However, this method was used primarily to gather anecdotes and not to judge the validity of the findings about program performance. For example, as we explain later, some of the delays were directly attributable to the way the Biden administration launched the program, specifically, inadequate guidelines delayed the launch of many projects. However, other interviewees reported that they paused or canceled projects out of fear that the Trump administration would kill or sabotage the program. Thus, the interview results are more of a feel than a diagnosis.

Other obstacles, like labor shortages and declining demand, fall into the “unforeseen” category. But there’s more going on than meets the eye in at least some of these cases. For example, weak demand for EVs in the U.S. is largely due to the inability of U.S. automakers to build these vehicles at low prices… while China can. And an adequate supply of charging stations is another concern for U.S. buyers.

On the subject of “labor shortages,” I hope knowledgeable readers will comment on whether this obstacle is due to an actual shortage of workers with the relevant skills (which is quite possible) or to employers’ unwillingness to pay high wages to attract workers (especially if those workers have to relocate).

Excerpt from the article:

The President’s Inflation Control Act and the Semiconductor and Science Act provided more than $400 billion in tax credits, loans and grants to promote the development of America’s clean technology and semiconductor supply chains.

But a total of $84 billion in projects worth more than $100 million have been delayed for anything from two months to several years, or suspended indefinitely, an FT investigation found…

The delays call into question Biden’s bet that an industrial transformation will bring jobs and economic benefits to a U.S. that has shifted manufacturing overseas for decades.

The point this little blog and many others make is that it will take 10 to 20 years to regain our manufacturing prowess, if it ever gets there at all. The US has not only abandoned so many skills at all levels (not just the factory floor but also supervisors and managers) but has also gutted public education so that many workers may not be able to perform key roles without remedial training. For example, I have occasionally seen complaints from manufacturers that they cannot find workers who can read blueprints, or worse, that their reading and numeracy skills are too weak to fill certain roles.

Let’s go back to our original topic:

Among the largest projects on hold are Enel’s $1 billion solar panel factory in Oklahoma, LG Energy Solutions’ $2.3 billion battery storage facility in Arizona and Albemarle’s $1.3 billion lithium refinery in South Carolina.

Many of the delays have been public, but some are unannounced. About 40 minutes away from the idle Albemarle site is a facility where semiconductor maker Palidus announced last year it would relocate its headquarters from New York and start manufacturing operations. The company will invest $443 million and create more than 400 jobs. Operations were scheduled to start in the third quarter of 2023, but the building remains vacant.

“We’re watching with bated breath to see what happens,” said Ted Henry, the mayor of Bel Air, Kansas. Integra Technologies announced last year that it would build a $1.8 billion semiconductor fab in Bel Air, Kansas, but the project has not moved forward because of uncertainty over government funding.

Henry was clearly willing to talk, but the reporter didn’t seem to want to find out what the “uncertainty about government funding” was.

We later find out that this could be the reason… but why not confirm it?

The IRA tax credit has been extended through 2032, and while the CHIP Act provides large amounts of funding to selected applicants, companies often can’t receive the funds until they hit certain production milestones.

The article goes on to give examples of “government procedures slowing things down.”

Some of the delays are policy-driven: delays in rolling out government CHIP Act funding for semiconductor projects and a lack of clarity on IRA rules have stalled many projects.

Electrolyzer maker Nelhydrogen has suspended plans to build a $400 million factory in Michigan due to uncertainty over hydrogen tax credit rules, while Georgia battery parts maker Anovion has delayed construction of an $800 million factory for more than a year due to a lack of clarity over IRA electric vehicle regulations.

The article states that in the first year of the IRA, participating companies announced investments of over $220 billion, including projects that were “reshored” from overseas. However, we then learn that many faced rising labor costs and supply chain issues. However, we are not told what those supply chain issues were. One example is actually downstream, not upstream. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) postponed the construction of its second factory. This hit its suppliers, Changzhong Group and KPCT Advanced Chemicals, which suspended their projects. The article suggests that the latter two are also beneficiaries of the IRA, but it is not as clear. But in any case, the usual understanding of supply chain issues is a lack of necessary inputs, such as when automakers are stuck unable to get the electronic equipment they need during the COVID recovery period. Here, we do not know exactly why Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) postponed the construction of its second factory, but the lack of orders caused suppliers to refrain from expansion.

The article explains how a sudden drop in solar panel prices due to a Chinese oversupply, combined with the oft-lamented slump in EV demand in the US, has led to the halting of some of the IRA projects.

Finally, the article explains that Republicans really hate IRAs, and no Republican senator supports the bill, even though it could benefit their own districts.

Ironically, if Republican beneficiaries were to proceed with the IRA program, it would be much harder for the Trump administration to stop it. They may need to find ways to subtly gut the program while inheriting projects that are already underway. Thus, delays and halts due to political concerns could end up being complacency.

Mind you, this was very informative detective work, and it’s a shame the editors didn’t let the writers investigate a bit further to come to a more solid conclusion.