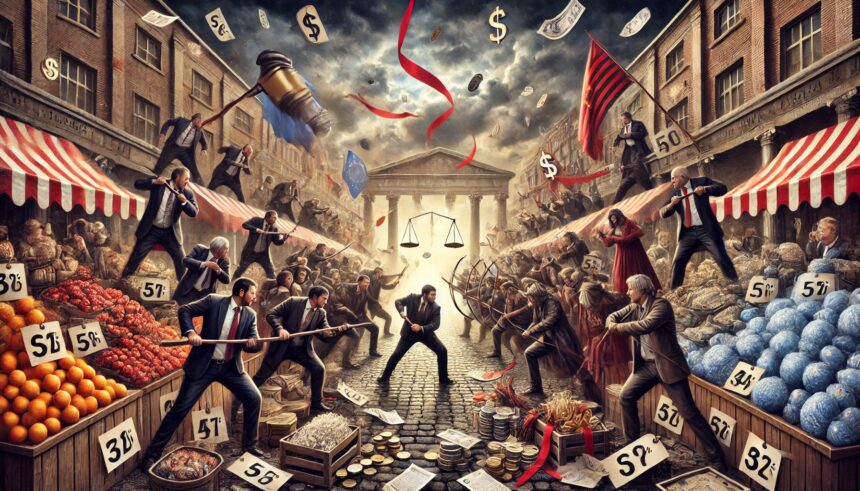

- Book Review Price wars: How common misconceptions about inflation, prices, and value lead to bad policy. Ryan A. Vaughn, ed.

PUS price controls have become increasingly common in large sectors of the economy, such as finance and health care, following the implementation of laws such as Dodd-Frank and Obamacare. President Biden’s recent move to cap late fees on credit cards and his broader opposition to what he calls “junk fees” are the latest examples of a growing anti-market price stance in Washington, and price controls now play a leading role in the presidential campaign. As a result, the new edited book Price wars: How common misconceptions about inflation, prices, and value lead to bad policy The Cato Institute report comes just in time to address the problems caused by price controls and inflation.

Editor Ryan Vaughn, quoting economist Alex Tabarrok, wisely points out that “prices are signals wrapped in incentives.” That is, market prices convey information about scarcity and the nature of consumer desires. Prices also motivate businesses to produce what people value and individuals to conserve resources where they are scarce. Biden’s junk-price policy fails to recognize this important adjustment mechanism of prices.

Tying the invisible hands

Whereas once conventional wisdom held that price caps would lead to shortages and price floors would lead to shortages, price controls are now suddenly all the rage. The book’s publication coincides with startling changes in the regulatory environment. For example, in 2023, the Biden administration’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) repealed some of its guidance to federal regulators encouraging agencies to refrain from enacting “economic regulations” such as price controls and quotas. OMB’s latest move will likely make it easier to implement such policies in the future.

While the harmful effects of price controls may be immediately obvious, such as long lines at gas stations in the 1970s or the rationing of groceries during World War II, in other situations their harms can be harder to detect, which is part of why price controls are becoming popular again. In his chapter on health care markets, Michael Cannon points out that government-fixed ceilings on health care prices are often too high relative to market equilibrium levels, resulting in excess spending that is largely invisible because the costs are paid by the government. Meanwhile, price controls on financial products make it harder for poor and other marginal communities to obtain credit. Restrictions on access to loans to buy homes and cars, and rising interest rates on credit cards and mortgages, are less visible than long lines at the gas station.

Other effects of price controls are harder to predict. Vaughn’s chapter on World War II price controls documents how price ceilings not only created shortages but also unanticipated declines in quality as companies responded to falling profits. Similarly, Jeffrey Clemens’ chapter on the minimum wage shows how workplaces often cut benefits before putting workers on unemployment benefits, suggesting that the real world is messier and more complicated than introductory economics theory suggests.

Myths and misconceptions about currency

In addition to dealing with the issue of price controls, Price War This book serves as an excellent introduction to inflation and its root causes. Brian Katzinger correctly criticizes the economic fallacy of the “wage-price spiral,” in which workers’ demands for higher wages induce companies to raise prices, which in turn induces workers to demand even higher wages, creating a self-perpetuating inflation. Brian Albrecht points out that “greedflation” similarly confuses cause and effect. Inflation is fundamentally a monetary phenomenon caused by excessive monetary growth. Inflation boosts nominal corporate profits, not the other way around.

Author Stan Voeger provides a useful overview of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a relatively new economic theory “born” in the blogosphere. MMT’s emphasis on the importance of money is consistent with the monetarist views of some of the book’s contributors. MMT argues (and I believe this is correct) that monetary policy can in theory be relaxed by Congress injecting new money into the economy, or tightened by raising taxes. In reality, however, policy never works this way.

The problem with MMT isn’t that the theory is flawed, but that it ignores the political realities that make using fiscal policy to control inflation impractical. Politicians are usually reluctant to raise taxes for fear of losing the next election. Even if they could raise taxes by the exact amount at the exact time (a big assumption if Congress can’t pass a budget on time), politicians would need to refrain from spending the revenues to control inflation, and they are unlikely to demonstrate such restraint.

As for areas where there is room for improvement, some of the book’s contributors argue that journalists are to blame for the public’s economic ignorance regarding inflation. Pierre Lemieux, for example, blasts journalists who argue that inflation is “caused” by price increases in various product categories in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Price indexes have well-known limitations, and Lemieux is right to point out their shortcomings. But some of Lemieux’s complaints sound whimsical. Journalists are technically correct when they point out that the prices of certain goods, such as eggs and milk, “contribute” to the rise in the index. Even if these journalists sometimes use sloppy language that can be mistaken for the cost of living index and inflation being the same thing, it is unclear how influential these news articles are. Despite their imperfections, indices like the CPI are still useful for tracking overall price trends and detailing how inflation affects different parts of the economy at different times.

The limits of laissez-faire

meanwhile Price War While the advantages of market prices are thoroughly explained, the paper misses the opportunity to discuss some of their disadvantages. For example, the incentives that market prices provide are often counterproductive in the presence of externalities or other market failures. In such cases, prices may encourage the diversion of production away from efficient uses.

A good example is the high salaries of athletes, which Deirdre McCloskey has defended, but there are still reasons to be skeptical of this free market outcome. Even if those salaries are the result of strong consumer demand for sports entertainment with athletes demonstrating rare physical abilities, society would be better off if consumers had priorities other than sitting on their couches watching sports, and if young people spent their time building more productive forms of human capital. McCloskey is right to point out that market prices tell us nothing about what people essentially “deserve.” But many market prices reflect the public’s desire to engage in conspicuous consumption. It would be economically efficient if we lived in a world where scientists and engineers were valued as highly as actors and athletes in our culture.

Price controls do have some benefits. If the controls imposed during World War II increased production capacity for military goods, why would similar restrictions in peacetime not increase production capacity for other valuable items that are normally underproduced? The sacrifices that some price control policies make, in the form of consumers accepting lower quality and quantity of consumer goods, also have benefits. This is especially true when the sacrifices are the result of consumers freely choosing to save and invest more and consume less.

The objective nature of subjective values

“Value is ‘subjective’ in the sense that a painting is worth different things to different people, because value comes from personal taste. But the actual resources consumed by government intervention – land, labour and capital – are objective phenomena.”

The book’s chapter on value is also somewhat lacking in detail with regard to distinguishing between the determinants of value and economic cost. Value arises from personal taste, so the value of a painting is “subjective” in the sense that it varies from person to person and depends on mental considerations. But the actual resources consumed by government intervention in the form of land, labor, and capital are objective phenomena.

In this sense, it is misleading for economists to use the word “subjective” when describing the value of resources. Private (individual) and social (total) economic costs are objective concepts that belong to the realm of empirical economics. Costs can be calculated scientifically, but that does not mean that it is always easy. An objective understanding of costs does not negate marginalist or preference-based explanations of price determination. This fact is entirely consistent with what 19th century economists criticized as the “labor theory of value.” William Stanley Jevons, Leon Walras and Carl Menger It was completely destroyed. But to this day many economists mistakenly confuse objective costs with subjective explanations of price formation. Price War So, an opportunity was missed to set the record straight on this point.

The flaws were minor, but Price War This book is essential reading for anyone wanting to understand the economics of price controls and inflation. McCloskey’s core proposition is spot on: market failure is caused by the absence of markets. “The socially wise action, therefore, is to create markets where they do not exist, not to abolish them through collectivization or price controls.”

The challenge is to foster the creation of new markets while subjecting them to the ethical constraints and associated privileges that are inevitable for human flourishing. Ultimately, markets must be subordinated to certain inviolable constraints, such as rights and the protection of “sacred goods” like happiness and aesthetic beauty. McCloskey acknowledges that we must “make good choices about what to sell and what not to sell” while respecting the role of sacred values.

For more information on these topics,

whole, Price War This book gives readers the intellectual ammunition they need to fight misguided inflationary policies and price controls, but it stops short of declaring the total victory of the free market, leaving room for further discussion of the limits of letting markets be guided by indulgent consumer preferences and the ethical considerations that inevitably go into managing even the best-functioning and most efficient market forces.