This week is Naked Capitalism’s fundraising week. We’re pleased to invite 1,140 donors to join us as they have already invested in our efforts to fight corruption and predation, especially in the financial sector. Donation pageHere’s how to donate by check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Why are we doing this fundraiser?, What we accomplished last yearAnd our current goal is to More original reporting.

Hi, I’m Yves. This article introduces the premise that populism is bad, a thought-provoking premise in a nominally democratic system. Nevertheless, the authors use high-street store closures as an indicator of continued recession. They find that in the UK, these closures correlate with the propensity to vote for UKIP. Recommendations include long-term revitalization plans and short-term measures to improve appearance.

To be nit-picky, correlation is not causation. In New York City, several years after the financial crisis, vacant storefronts began to spread in upscale areas such as Upper Madison and Third Avenue on the Upper East Side. The most upscale areas of Madison Avenue, from 57th to 72nd Streets, also saw unprecedented vacant storefronts. In the Upper Madison/Third Avenue case, we heard that landlords refrained from raising rents for several years after the crisis, then implemented overwhelmingly large increases, usually double the previous increases. And it was reported that no increases were made after 18 months or more of vacant storefronts. There is a long New York City-centric explanation for this behavior.

But the takeaway from this story is that the fact that so many stores remained vacant for so long (often 3-5 per block, meaning they were clearly visible) is unlikely to have led to a change in voting behavior. The authors of the analysis found that the tendency to move to the right was strongest among the unemployed. Manhattan is a very expensive place to live, so you need a decent income, i.e. a job or lots of assets, to stay there.

As for the proposal to clean up downtown areas with all the closed shops, at first it seemed like an exercise in Potemkin village building. But I hate to say it, that kind of thing is probably psychologically irritating. Where I live now was hit hard by the Asian crisis, the 2007-2008 crisis, and as a tourist destination, by the corona pandemic. Except for the busiest places, such as along the beach, there are still closed shops and too many places that are shabbier than they should be. When the taxi driver can converse in English, I sometimes complain that the city should invest in painting the 20% of the worst-looking buildings on the main roads, that it would make a big difference to the look of the city, and that they should subsidize the replacement of the badly damaged banners. And then I find myself thinking that when I see a partly vacant building that has recently been painted, it will attract new tenants. So I am having exactly the reaction that is supposed to be in this article.

Another way to look at the findings is that any spending to show these towns have not been forgotten, even if the impact is superficial, is better than nothing.

Authors: Thiemo Fetzer, Professor of Economics, University of Bonn, Theme Leader on Globalization and World Crises at the Centre for Competitive Edge in the Global Economy (CAGE), Professor of Economics, University of Warwick, Jacob Edenhofer, PhD student in Politics, Nuffield College, University of Oxford, Prashant Garg, PhD student, Imperial College London. Vox EU

Support for right-wing populist parties in many advanced democracies is characterised by considerable regional variation. In this column, we use data from high-town job postings in the UK to show that visible signs of local decline play an important role in increasing support for right-wing populists. One key policy implication is that countering populism requires not only local policies that deliver long-term results, but also measures aimed at reducing visible signs of decline in the short term.

Support for right-wing populist parties in many advanced democracies is characterised by considerable regional variation, with these parties being particularly successful in areas where manufacturing has traditionally been a large part of local economic activity (Autor et al. 2020; Broz et al. 2021; Guriev and Papaioannou 2022; Rodríguez-Pose 2018; Rodrik 2021). Often, these areas also suffer from visible externalities of economic downturn and austerity (Fetzer 2019), providing fertile ground for populist sentiment, including vacant downtown stores, homelessness (Fetzer et al. 2023) and rising crime (Bray et al. 2022; Che et al. 2018; Facchetti 2023, 2024; Fetzer 2023). A new paper (Fetzer et al. 2024) explores the relationship between local economic decline and support for right-wing populism. Specifically, we use new data on vacant posts in busy streets in England and Wales to explore how this visible indicator of decline affects political behavior.

Vacant properties in downtown areas are an indicator of neighborhood decline

Our main contribution is empirical, namely, that we collect new data on vacant downtown storefronts. This is important because vacant storefronts are a visible and powerful indicator of local economic decline. Being visible, downtown storefronts are a particularly good proxy for local economic decline, and individuals are therefore more likely to use them to update their thoughts about local economic activity. Other indicators, such as municipal-level unemployment rates, are noisier and harder to recognize as signals of local economic activity, and therefore less likely to shape attitudes and political behavior. We therefore improve on previous studies of the impact of neighborhood decline on populist support, notably those of Arzheimer et al. (2024) and Green et al. (2024), in one important respect. These studies used survey items related to neighborhood decline to measure neighborhood decline, and there is a risk that their results will be influenced by misinterpretations and misreporting of decline. By utilizing an objectively measurable, concrete, and highly visible component of decline, namely downtown storefront vacancy, we avoid this problem.

The rise in vacant jobs may itself be the result of structural change, namely the shift from offline to online commerce since the late 2000s, and the disparate effects it has across communities. Structural change may have beneficial effects on consumer welfare, but it may also have highly heterogeneous effects across individuals if the form of consumption is itself considered a valued social consumer good that contributes to a sense of connection, belonging, and community cohesion.

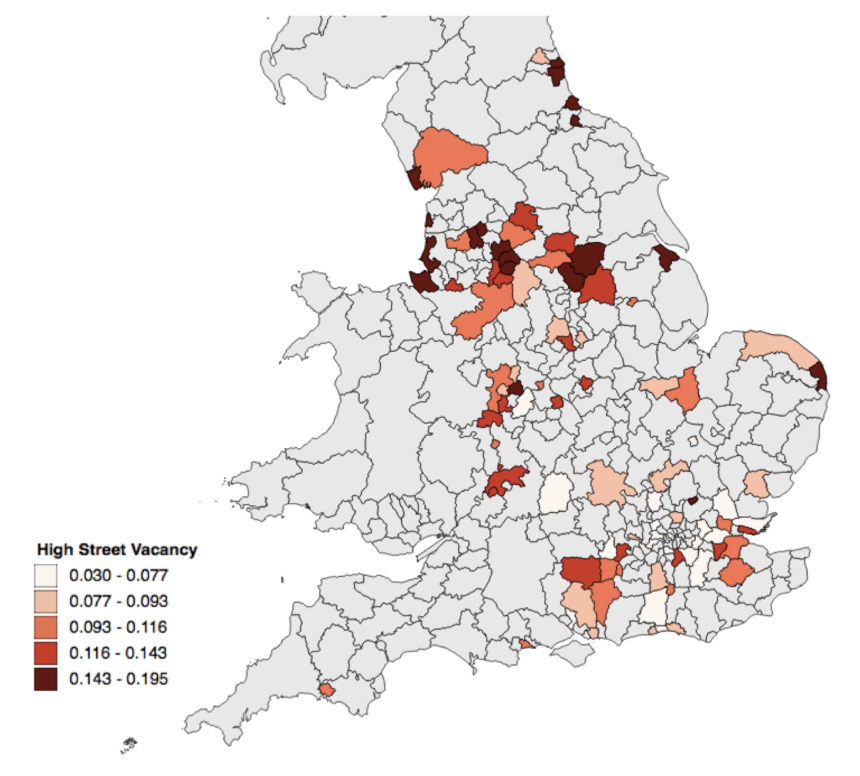

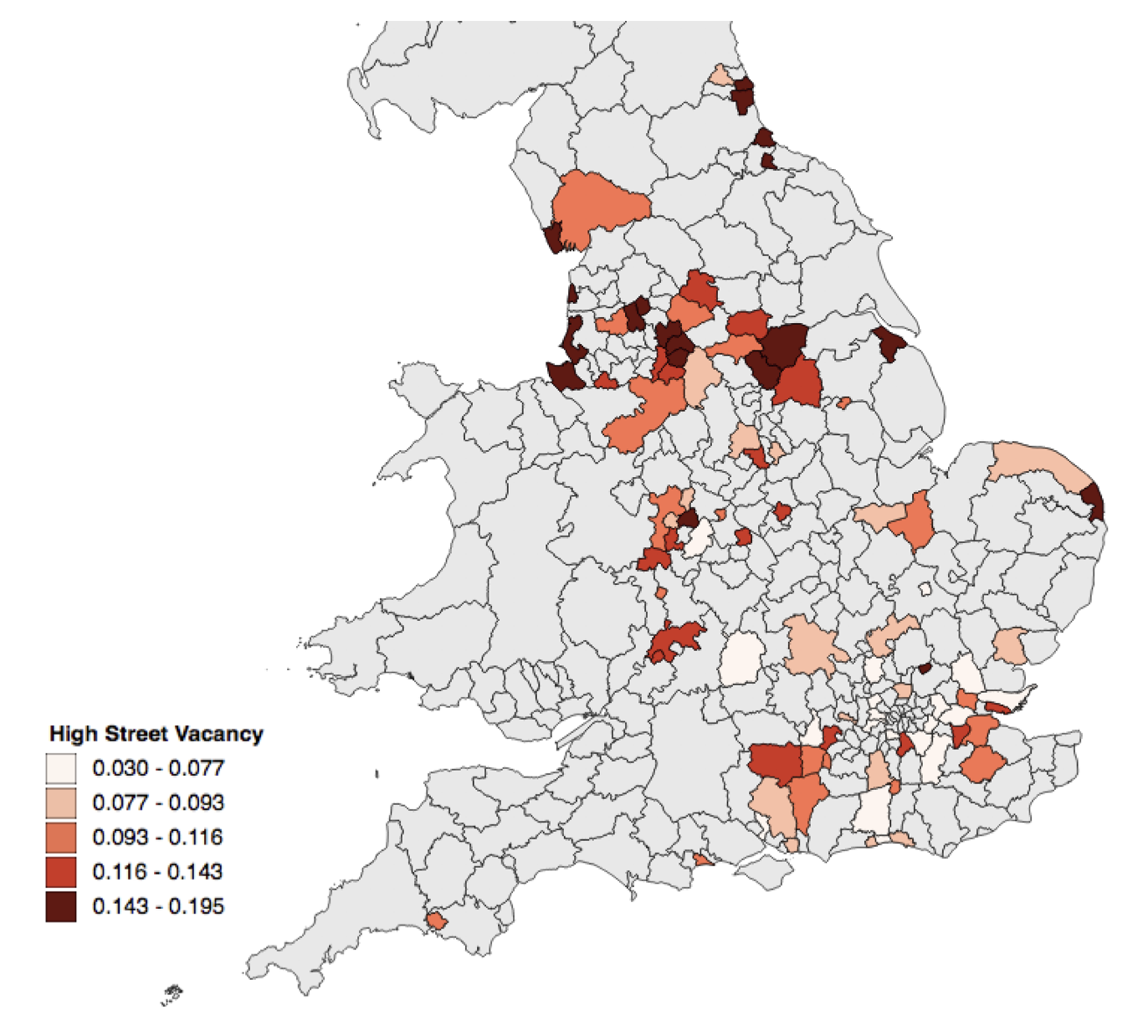

The study uses data from the Local Data Company (LDC), which covers around 83,000 commercial premises in 197 towns across England and Wales between 2009 and 2019. The data shows that there are significant regional variations in vacancy rates, with high concentrations in the North East of England, where many areas saw a significant increase in vacancy rates after the 2008 financial crisis.

Figure 1 Geographic distribution of vacant properties in downtown areas

NoteThis figure visualizes the geographic distribution of vacant high street shopfronts by local authority in England and Wales. The map shows considerable regional variation, with the North East of England having primarily high vacant shopfront rates, with many local authorities having vacant shopfront rates above 10%. The data covers approximately 83,000 physical premises in 197 towns across 93 local authorities from 2009 to 2019.

The concentration of vacant downtown storefronts in certain areas, particularly in the Northeast, highlights the uneven impact of economic decline across the country. These vacant storefronts are not just a symptom of the economic crisis, they are also helping to shape the political landscape by reinforcing perceptions of neglect and decline.

The rise of UKIP and the role of regional decline

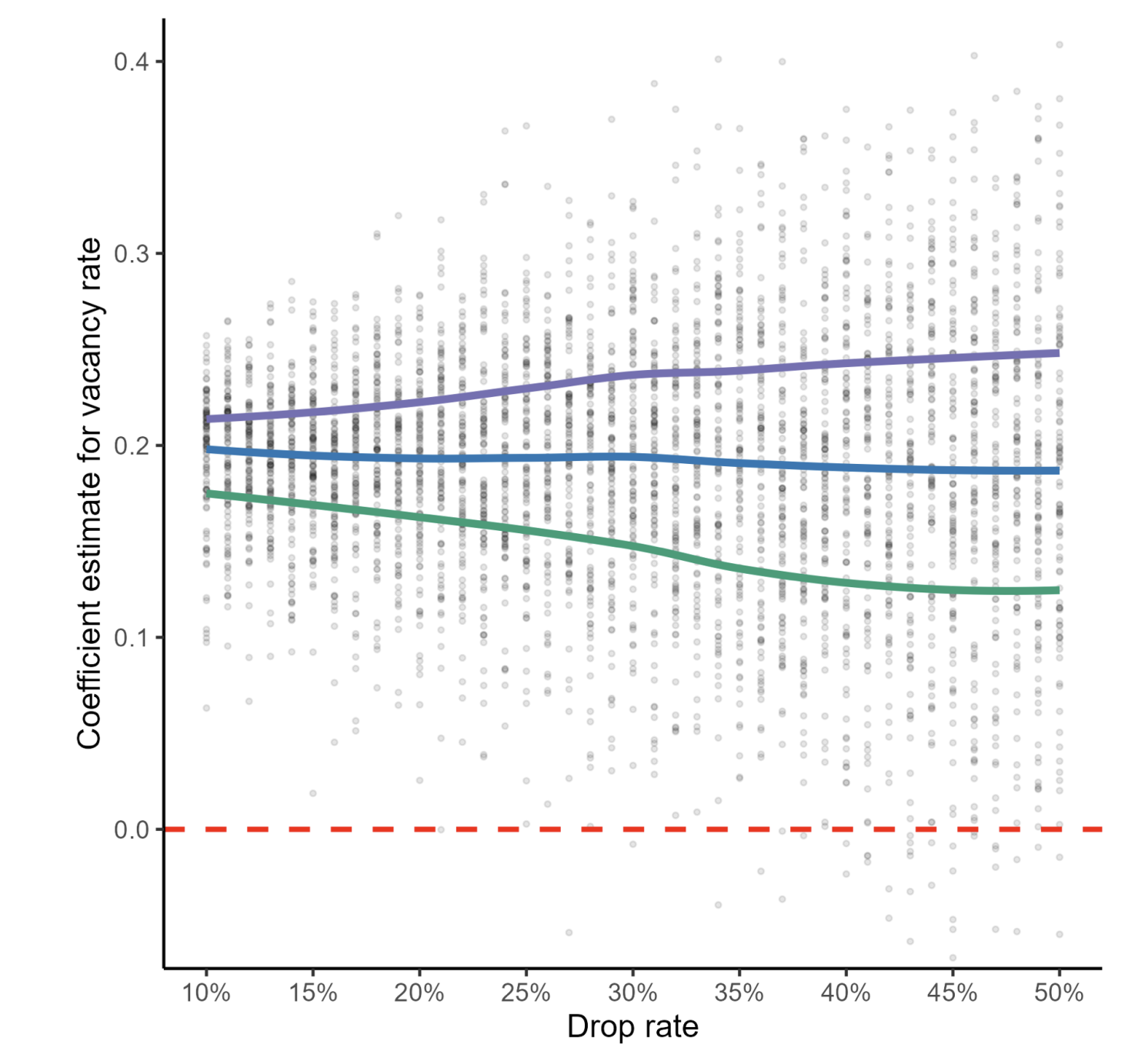

The UK Independence Party (UKIP) capitalised on these sentiments to garner strong support from areas experiencing severe economic decline. We use data from the Social Understanding Survey to track political preferences over time and investigate the relationship between vacant high street posts and support for UKIP. Our analysis reveals a strong positive correlation between vacant high street posts and support for UKIP, even after controlling for a range of individual and local factors.

Figure 2 Highway vacancy rates and UKIP support

NoteThe figure shows a positive correlation between high street vacancy rates and UKIP support. This relationship shows robustness when tested across different subsets of local authorities. The positive correlation remains strong even when randomly excluding some local authorities from the analysis. The purple line shows the overall trend, indicating that as vacancy rates rise, so does UKIP support. Consistent results across different scenarios strengthen the confidence of the findings.

The results suggest that visible signs of neighborhood decline, such as vacant storefronts in downtown areas, play an important role in driving support for right-wing populists. This relationship is not driven by individuals who are or have been employed in retail. This suggests that our results are driven by the populist facilitating effect of the spatial externalities of decline, rather than by increased economic insecurity at the individual level.

Diversity of populist support

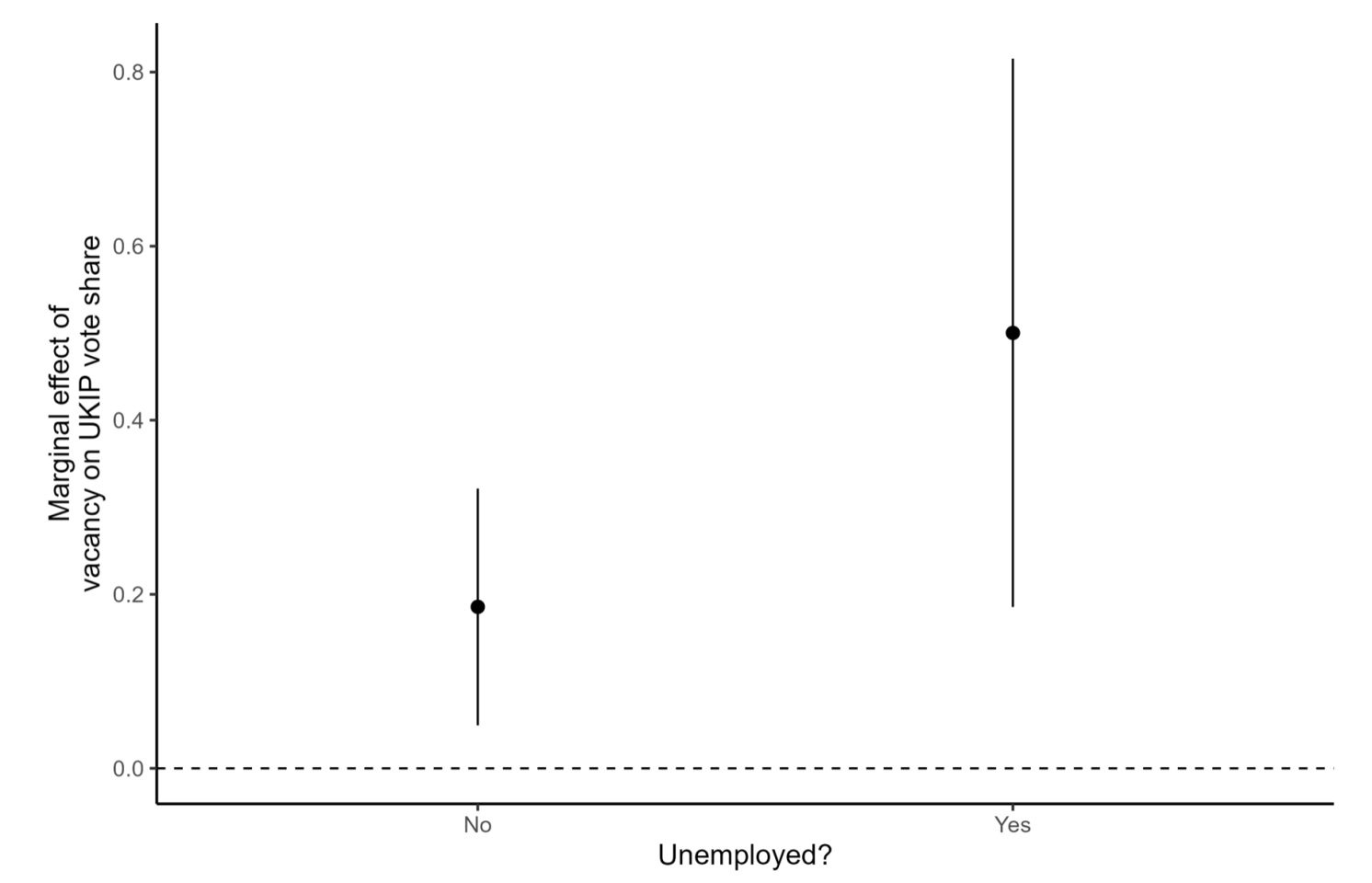

The effect of vacant high street posts on Populist support is not uniform across all regions and demographic groups: our research finds that unemployed people are more likely to support UKIP as vacant posts increase, reflecting their increased vulnerability to local economic shocks.

Figure 3 Variation in UKIP support by employment status

NoteThis figure shows the marginal effect of high street vacancy rates on support for UKIP by unemployment status, controlling for age, full homeownership dummies, dummies for chronic health conditions, and age and region-by-quarter fixed effects. The results show that the effect of high street vacancy rates on support for UKIP is significantly stronger for unemployed respondents, highlighting the sensitivity of economically weaker groups to local economic crises.

These findings highlight the importance of addressing the visible effects of economic decline in mitigating the rise of right-wing populism. Policies aimed at revitalizing declining downtowns and improving local economic conditions could play an important role in countering the appeal of populist parties. We expect that pandemic-induced urban-to-rural migration, especially the rise in remote work, could help reverse this trend.

Conclusion: Implications for policy and future research

This study highlights that visible local economic decline plays a key role in shaping political preferences and fueling the rise of right-wing populism. The visible impact of vacant high-town positions on support for UKIP highlights the need for targeted policies to address the root causes of economic decline and its spatial externalities. Future research should focus on more rigorously identifying and exploring the causal mechanisms underlying this relationship and identifying effective strategies to mitigate the negative impact of local economic decline on political behavior.

More broadly, our findings suggest that to halt the rise of far-right populists, equalisation measures that deliver long-term returns – including investments to improve the skills base of the workforce and infrastructure in declining areas (Bartik 2020; Gold and Lehr 2024; Lee 2024) – may need to be complemented with shorter-term measures aimed at addressing spatial externalities, such as vacant high street shopfronts, which are particularly visible and recognisable.

look Original Post References