The story was not a fabrication.

The impetus for this post was an email from Marjorie Oye, widow of the late economist Walter Oye.

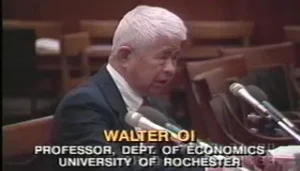

I wrote a letter of gratitude. Regulation 2014, shortly after Walter Oy passed away in December 2013. I often don’t like the titles my editors choose for me. I usually prefer the titles I choose myself. But I couldn’t have come up with a better title than the one my editors chose. Regulation Editor’s Choice:The moral vision of the blind economistThe statement highlighted Walter’s work in helping to abolish conscription and then blocking its reintroduction when its supporters tried to do so.

By the way, I’m re-reading this piece after not reading it for years, and I think it’s in the top 20 of the more than 400 popular pieces I’ve written.

Before I move on to the text that Marjorie sent me via email, I would like to quote a passage from her:

One example of Walter’s professional tenacity was his efforts to prevent the reinstatement of conscription. Since its abolition, there have been occasional calls to reinstate conscription. One such call was in the late 1970s, after several years of failure to recruit the best men the U.S. military needed. Senator Sam Nunn (D-Ga.) spearheaded the movement. Walter, like Meckling and Martin Anderson and Milton Friedman of the Hoover Institution, recognized the need to defend a volunteer military, and did so. In December 1979, he attended the Hoover-Rochester Volunteer Conference, the first conference on conscription since the Chicago conference in 1966. The papers and proceedings of this conference were collected into a book published in 1982. Registration and DraftWalter, who preferred simple sentences, offered a brilliant analogy to the argument that conscription enlisted the weak as well as the powerful: “The state of Massachusetts granted a reprieve to all its members of the state legislature and to the fellows of Harvard College,” Walter said.

Now, regarding the passage in my article that Marjorie mentioned.

I first met Walter when I was a graduate student at UCLA and he came to present a paper on workers’ compensation in a law and economics seminar that I was running at the time.

Walter was pretty far along in his presentation, he actually had some numbers on the board and, if I remember correctly, an equation or two. I was sitting next to a student named Ed Rapaport. Ed raised his hand because he wanted to ask Walter a question. He kept his hand up, so I whispered to him, “Ed, he’s not going to ask you a question because he’s blind.” “Really?” Ed replied. “Yeah, that’s why the dog sits in the corner,” I replied. That’s how good Walter was at presenting.

The following story may be fiction, but I believe it to be true: Walter was at a conference where another economist was writing a long equation on the board.

The economist must have said that term out loud as he wrote it. Walter raised his hand. “Yes?” the economist said. Walter: “The third term in the equation. Isn’t that a minus sign, not a plus sign?” The economist turned and looked at the equation. He paused for a moment and said, “Oh, I see. Thank you.”

It turned out that this story was true, and here’s why. In a September 18th email, Marjorie wrote:

I was looking for information for my daughter (Eleanor) to use in a presentation about Walter’s work finishing up a draft. One of the articles I sent her was a Cato article about Walter. In it, it mentions a story about Walter noticing an incorrect equation at a seminar in Rochester. Now I can confirm that the story is true. A former student of Walter’s (X – Marjorie has not received permission to name and quote him) just moved into my retirement community. He was a graduate student and was in the seminar where Walter pointed out the error. I’ve heard that story many times from many people, but never from a primary source. (Franco) Modigliani was giving the seminar. I hope you’re well.