Hi, I’m Eve. This study addresses an important topic: what causes health inequalities by income group? It’s widely known that wealthier people generally have better health than poorer people, but how does that happen? The data comes from Denmark, which has a very good health system that provides high-quality care to low-income groups. The key finding is that poor people have higher rates of chronic disease and develop it at a younger age than wealthier people. This is not primarily due to health care disparities. Once a disease is diagnosed, the outcomes are similar across income groups. However, the authors point out that less wealthy people may have their diseases diagnosed later, and that better preventive care might have prevented them from developing chronic diseases.

The article does not discuss the extent to which environmental factors such as living in areas that can directly harm health (poor air quality from living near a traffic highway, increased exposure to toxins from living near a chemical plant) or jobs that can harm health contribute to the health gap. Readers are encouraged to tell the extent to which low-income Danes eat unhealthy foods, which is a major cause of obesity in the United States.

Of course, causation works in the other direction too: people suffering from chronic illnesses may find it harder to progress to higher incomes.

Authors: Kaveh Danesh, Resident in Internal Medicine, University of California, San Francisco; Jonathan Kolstad, Associate Professor, Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley; William Parker, PhD Candidate, London School of Economics and Political Science; Johannes Spinnewin, Professor of Economics, London School of Economics and Political Science. Vox EU

Health inequalities have long been a subject of research and debate, but the gap in life expectancy between rich and poor remains pronounced, even in countries with universal access to healthcare. In this column, we use data from the Netherlands to analyze the roots of health inequalities. Mortality differences are most pronounced in old age, but chronic diseases start to shape these disparities much earlier than is generally recognized. Socioeconomic status and geographical disparities play a key role in the development of chronic diseases, surpassing the effects of unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and drinking.

In the Netherlands, access to health care is nearly universal, with only 0.4% of poor households reporting unmet health care needs (Eurostat 2023). However, inequalities in life expectancy remain significant, with a difference of 7.6 years for women and 11.6 years for men across the household income distribution. This is in line with figures elsewhere in Europe and not very different from results in the United States (Chetty et al. 2016; Schwandt et al. 2021; Currie and Schwandt 2016; Bohacek et al. 2018).

Despite the importance of the issue and the attention it has received in policy and research, the complexity of health production functions, combined with difficulties in measurement, means that our understanding of the causes of health inequalities is limited. As Angus Deaton has noted, “there is no general agreement about their causes…and what appears to be agreement is sometimes supported by repeated assertions rather than by hard evidence” (Deeton 2002).

Our new study (Danesh et al. 2024) focuses on chronic diseases and studies how health disparities develop across the life cycle. Chronic diseases are not only important drivers of mortality and income gradients, but also measurable and dynamic markers of population health (Bloom 2022). This study therefore allows us to track important health indicators that contribute to mortality disparities in late life, long before their mortality effects are apparent. Building on previous studies (e.g. Huber et al. 2013), we identify chronic diseases using dispensed medications. These data are available at the individual level for the entire Dutch population since 2006. Using additional information from survey data and other medication use, we directly address concerns about unequal underdiagnosis and inappropriate management of chronic diseases. We find that detection and medication rates are consistent across the income distribution, except for the lowest 5%–10%.

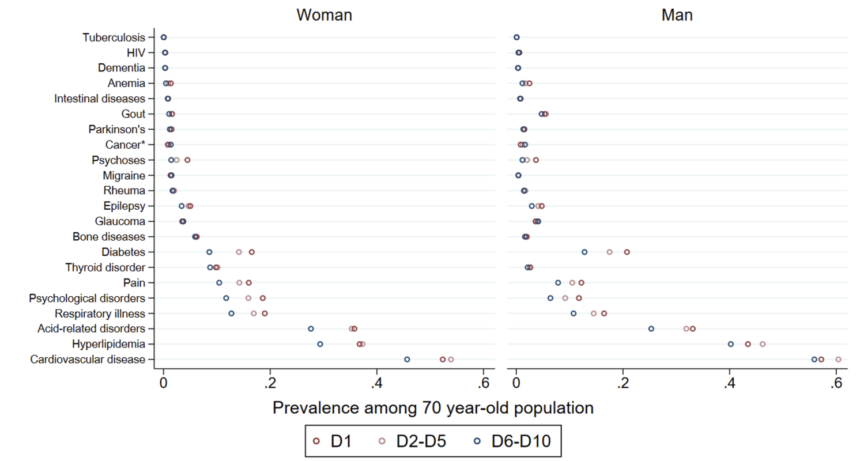

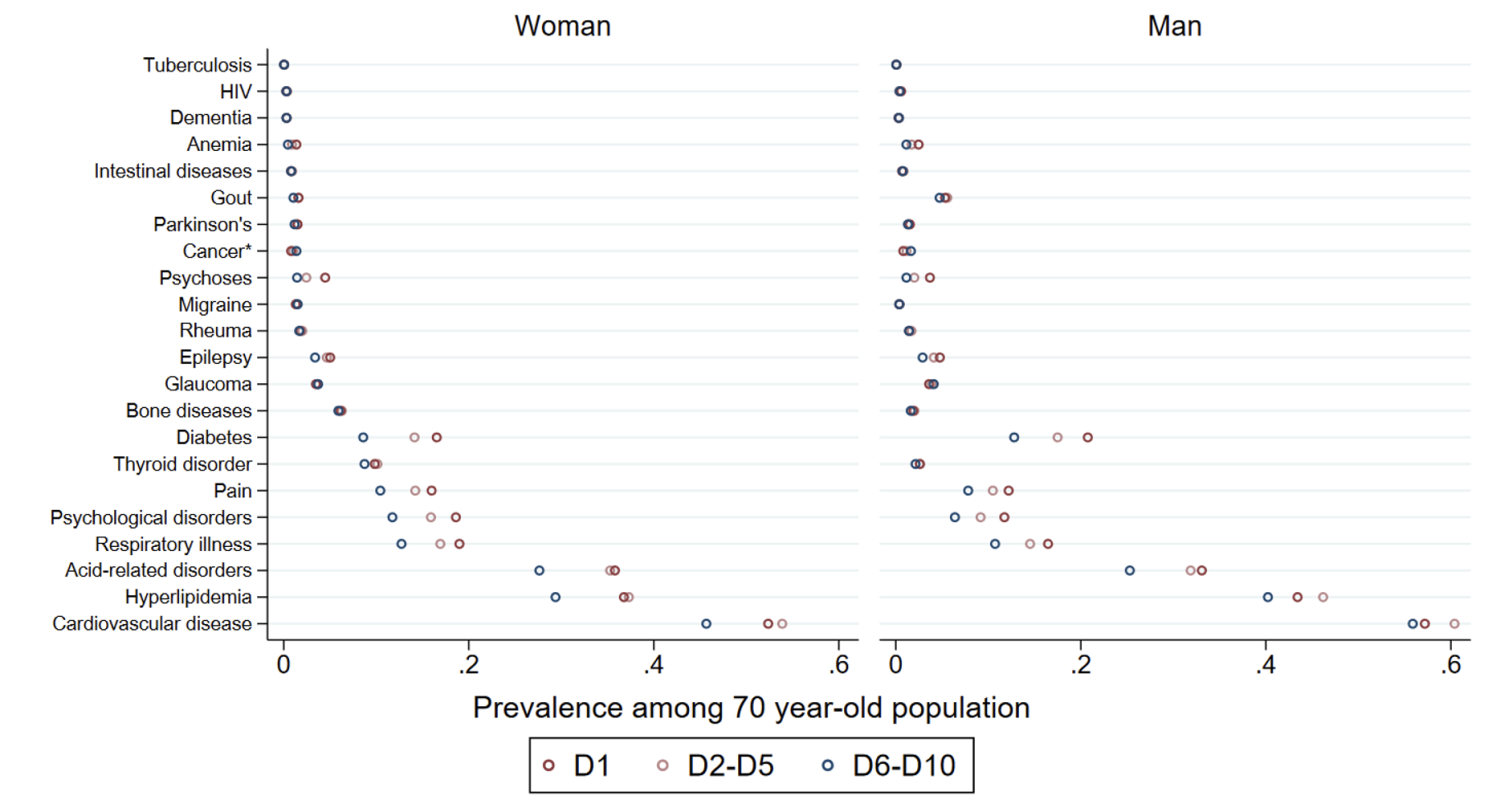

Figure 1 plots the prevalence of all chronic diseases in old age, highlighting their higher prevalence in people with household incomes below the median. Isolating the bottom 10% (D1), we show that this group has a lower prevalence of some diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disease), which could be due to poor diagnosis and management. Overall, we find that differences in chronic disease prevalence explain 30-40% of the difference in old age mortality between low-income and high-income groups. Furthermore, we find no significant differences in mortality conditional on chronic disease, suggesting that people diagnosed with a particular chronic disease receive similar quality of care regardless of income group. This is further supported by similar health care costs conditional on chronic disease across the income distribution.

Figure 1 Differences in chronic disease incidence by income at age 70

The dynamics behind mortality disparities

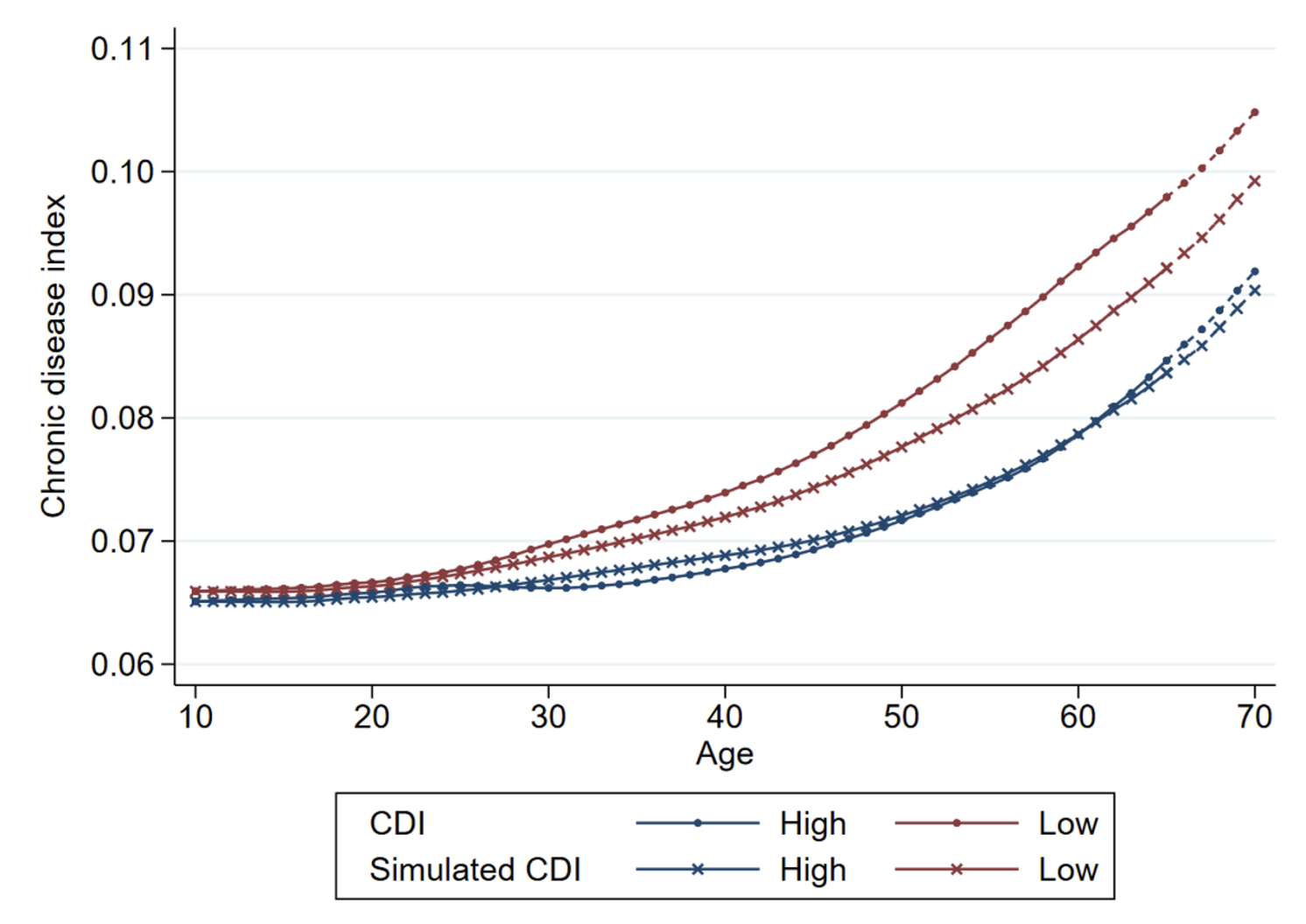

While disparities in mortality risk are most pronounced at retirement ages, our analysis shows that these forces are established earlier in life. We create a Chronic Disease Index (CDI) for all individuals and all ages, capturing how chronic diseases at that time predict mortality risk in old age. Figure 2 visualizes how the average CDI changes over the life cycle, separately for low- and high-income individuals. This dynamic series reveals that half of the disparities measured at age 70 are already realized at age 40, indicating that early interventions are needed to close health disparities.

Two main factors are responsible for the widening health disparities with age. Differences in agingLow-income people develop chronic diseases at a faster rate. Health-Based Selectionthose with chronic diseases are classified into the low-income group. Figure 2 also shows the simulated CDI excluding the health-based classification effect, highlighting the rapid aging in early adulthood among low-income individuals. While both forces are important, our estimates show that differential aging is the dominant factor, contributing 40% more to the difference in chronic disease burden at age 70 than health-based classification.

This highlights that individuals from different income brackets follow different health trajectories and that interventions are needed to address the social determinants of health at an earlier age. incident Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and respiratory disease contribute most significantly to aging differences throughout adulthood. Spread Psychological disorders contribute most significantly to the gap in CDI levels already at a young age.

Figure 2 Health disparities throughout the life cycle

Mediators of chronic disease

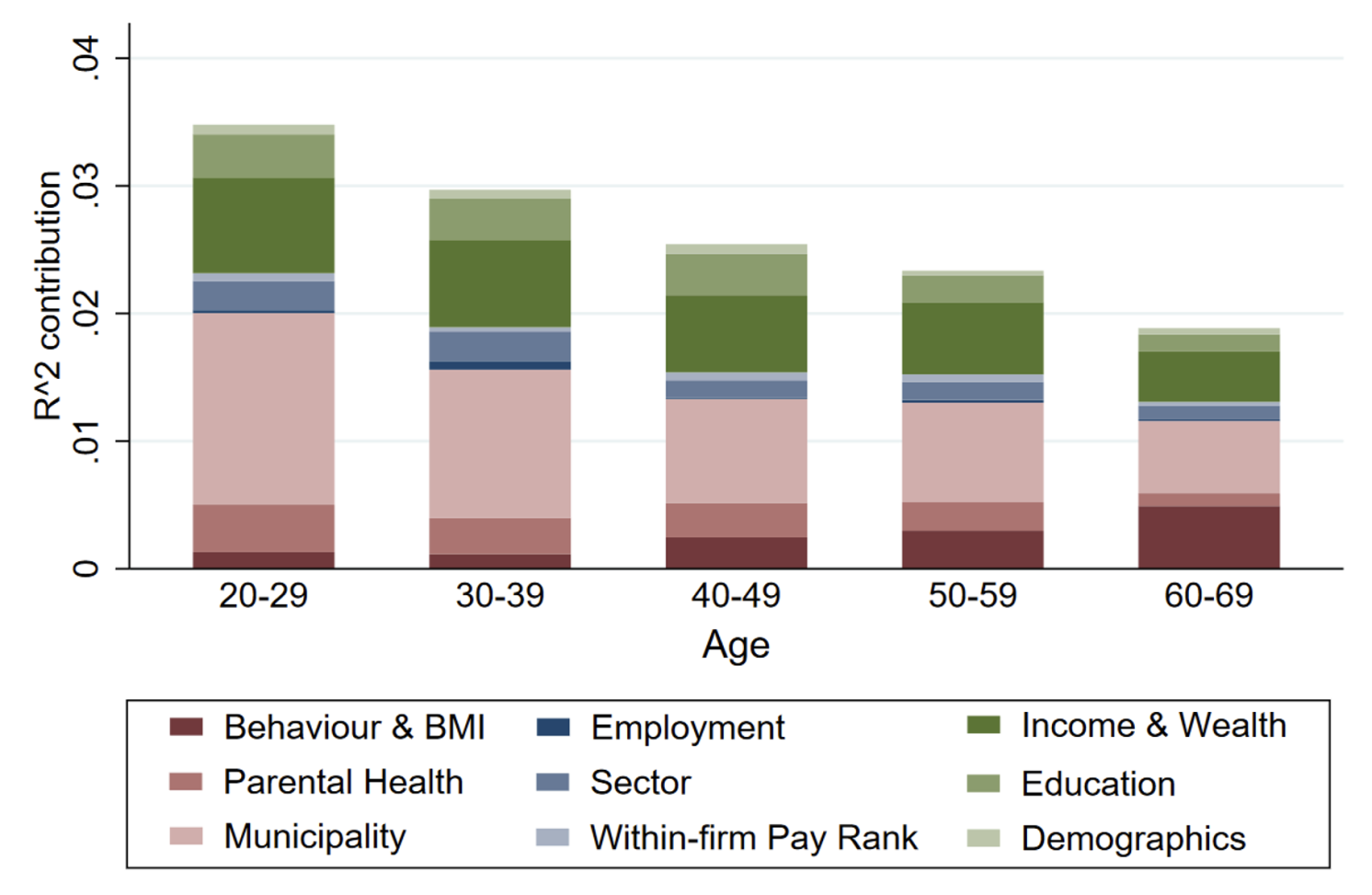

Establishing differences in health trajectories also allows us to uncover relevant factors mediating these trajectories. We exploit the rich data environment in the Netherlands, which includes not only various administrative registers but also linked survey data. In contrast to previous studies, we are able to account for different mediating factors together in the same context, thus providing a comprehensive description of their relative importance. Using a Shapley-Owen decomposition, which allocates the variation commonly explained by different mediating factors, we find that socioeconomic status and geography contribute most to the explained variation in chronic disease incidence, each accounting for about one-third. Figure 3 illustrates these findings. In contrast, we find that the role of observed health behaviors (smoking, drinking, physical activity, BMI) and occupational factors (e.g. field of work, wage rank within the company) is less significant.

Although this analysis is descriptive, it provides an important recalibration of the potential importance of different determinants of health, as previous studies have emphasized individual health behaviors as the primary driver (e.g., McGinnis et al. 2002). Interestingly, the richness of the data allows us to demonstrate the potential for error in estimation due to data challenges, particularly in showing that more partial analyses (e.g., not controlling for other social and geographic factors) or not considering reverse causation (e.g., investigating prevalence rather than incidence) would overestimate the importance of commonly measured health behaviors.

Figure 3 Relative importance of mediators in the 5-year growth of CDI

Conclusions and policy implications

In many countries, health expenditures are directed almost entirely at treatment, despite the high payoffs of prevention. Our analysis strengthens the case for investing in preventive policies by showing that prevention has the potential to reduce health inequalities. In particular, our study shows that differences in the incidence of poor health are a more important driver of health inequalities than differences in treatment. Furthermore, we find that health inequalities start much earlier than traditionally recognized, with large disparities already evident in middle age. A key driver is differential aging across income groups, which disadvantages those with lower incomes. Addressing this disparity early in life is essential to reduce health inequalities.

Effective policies should move away from current efforts that focus on unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and drinking and instead emphasize interventions that target early-life health determinants. In particular, socioeconomic status and geographic disparities play a key role in the development of chronic diseases, beyond the influence of individual health behaviors. Comprehensive strategies to address these factors before they lead to chronic diseases are essential to creating a more equitable health environment.

look Original Post References