Hi, Yves. This article does a great job of countering the whining of big pharma companies complaining about being subject to price regulation. And to sum it up even shorter: drug prices and healthcare in general are not market goods. If a drug or treatment is critical to survival, people will pay whatever the price. AOC made this point well in her heyday.

“People’s lives are not a commodity… You can’t ask them how much they would pay to live, because the answer to that is everything.”

That’s why the price of a drug is different from the price of an iPhone.” @AOC pic.twitter.com/j4DTOR7VgI

— Social Security Works (@SSWorks) May 16, 2019

Article by William Lazonick (Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Lowell and Chairman of the Air Research Network) and Honor Tulum (Postdoctoral Researcher at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London and Senior Research Fellow at theAir Research Network (theAIRnet)). Institute for New Economic Thinking Website

Drug price negotiations between Medicare and pharmaceutical companies under the Inflation Control Act face a complex question: what is the “Most Fair Price” (MFP) for prescription drugs? The higher the price of an “MFP” drug under negotiation, the more unaffordable it is for the health system. However, negotiators agree that the price of an MFP drug should be enough to allow pharmaceutical companies to invest in their next round of drug innovation. The question is: with this trade-off in mind, how high is “fair”?

Pharmaceutical companies argue that regulated drug prices are “unfair” because they should be determined by the “market.” But as our new INET working paper shows,Drug pricing: What Medicare negotiators need to know about innovation and financializationIn the United States, the combination of a cost curve showing economies of scale and a revenue curve reflecting the price inelasticity of demand for essential drugs means that the market cannot set the price. In other words, as companies increase production, the price falls, but people often have to get the drug at any price. Unregulated prices are monopoly-like and likely involve an element of price gouging, especially given the fact that the U.S. gives pharmaceutical companies at least 20 years of patent protection for prescription drugs.

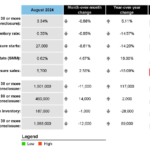

Moreover, as we noted in the INET paper, most of the pharmaceutical companies with whom Medicare currently negotiates MFP drugs do not use the profits from high prices for existing drugs to fund investments in pharmaceutical innovation. Over the 10-year period from 2013 to 2022, 14 pharmaceutical companies in the S&P 500 index distributed 105% of their net income to shareholders, a higher percentage than the highly financialized 98% of all 478 companies in the dataset. While pharmaceutical company share buybacks are lower at 51% compared to 57% of the 478 companies’ net income, pharmaceutical company dividends as a percentage of net income are much higher at 54% compared to 40% of all companies in the dataset. An easily demonstrable conclusion is that pharmaceutical companies are using high drug prices to fund dividends to shareholders. How is this fair?

The pharmaceutical company response is that if they do not “return” value to shareholders, then shareholders will not make risky investments in pharmaceutical innovation. The problem with this argument is that, contrary to conventional wisdom, incumbent pharmaceutical companies will not, as a rule, raise money in the stock markets to fund investments in production capacity; shareholders simply buy and sell outstanding shares on the stock market. How can a company “return” cash to shareholders who have not paid any cash at all?

Let’s look at some of the companies with whom Medicare is currently negotiating MFP drugs: Pfizer issued its most recent common stock on the public stock market in 1951, Merck in 1952, and Bristol-Myers (now part of Bristol-Myers Squibb) in 1952. Are shareholders who bought these shares over 70 years ago still demanding a “return” on their investment?

To bolster their unfounded claims, pharmaceutical companies rely on the now ubiquitous but deeply flawed ideology emanating from business schools and economics departments that only shareholders make risky investments in pharmaceutical innovation. Our INET paper refutes this view. The people who bear the much larger risks of investing in pharmaceutical innovation are American households, both as pharmaceutical company employees engaged in so-called “collective and cumulative learning,” and as taxpayers who have pumped more than $1.6 trillion into life sciences research at the National Institutes of Health since 1938, including $48.8 billion in 2024.

In recent years, pharmaceutical companies have been advocating “fairness” in drug pricing, arguing that the companies that sell drugs should be the ones to reap all of the “value to society” that drugs create by reducing treatment costs and increasing health benefits. Our INET paper summarizes the history of 10 MFP drugs currently under negotiation. Basic Research and Translational Research These are ex ante and external to the pharmaceutical company selling the MFP drug, and allow the pharmaceutical company to perform some (but not necessarily all) of the functions necessary to sell the MFP drug. Clinical Research This has allowed the Food and Drug Administration to approve these drugs as safe and effective.

In reality, pharmaceutical innovation is a multi-stakeholder collaborative effort that spans a very long time period. Academic institutions, government laboratories, and non-profit organizations play a key role in basic and translational research, providing the foundation for pharmaceutical companies to work on clinical trials. Most of this collective and cumulative learning process happens upfront, outside the pharmaceutical companies that commercialize the drug.

The countless people involved in these learning processes are not compensated commensurate with their “value to society” – both because they do not know their value to society when they are doing the work, and because, like the pharmaceutical companies themselves, they contribute to the vast historical process of collective and cumulative learning in basic, translational, and clinical research that makes drug innovation possible. When they come to the negotiating table, Medicare negotiators need a deep theoretical and empirical understanding of these learning processes in order to negotiate fair prices in terms of affordability of existing drugs and financial investment in the next drug innovation. As our INET paper “Drug pricing” introduces that perspective.