The period from 1870 to 1910, which includes the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, is universally described as a time of rapid progress. economic growth. This growth has been rapid and unevenly distributed, with the poorest 90% generally seeing far less improvement.

This common notion is probably wrong, given how existing data on inequality are used. In fact, inequality between the top 10% and bottom 90% of America’s income distribution has likely decreased.

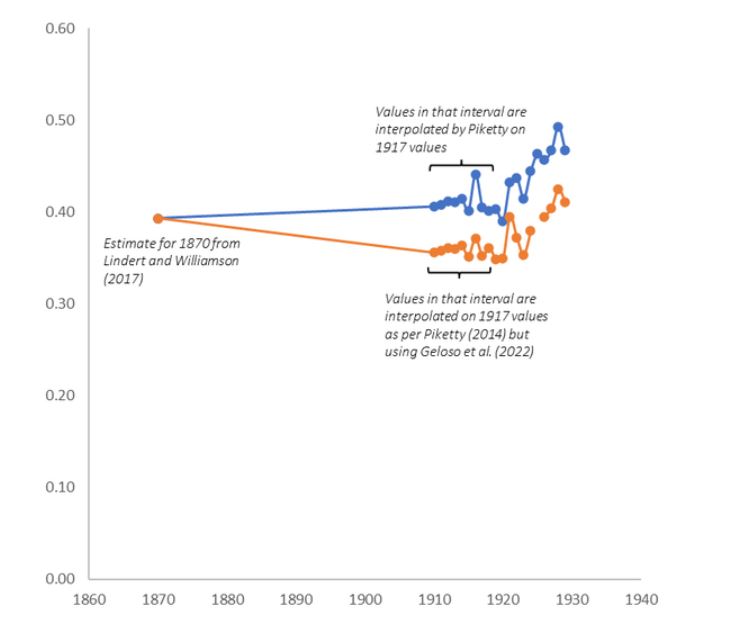

Let’s take a look at that data. At this time, there are no actual estimates for the period 1871-1909. There are estimates for 1870 and 1910.

Estimates for 1870 are: Works by Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson. They used what was known as a “social table.” This approach estimates income distribution by assigning average incomes to different social or occupational groups based on historical records such as census data. It also results in gross national income and income inequality. There is no objection to this assumption; if anything, it is probably express in an understated manner Inequality due to the problem of undercounting the poor in the census.

The 1910 estimate is based on Thomas Piketty’s famous book. 21 years capitalcent century, It is not directly based on income data. Instead, we used 1917 tax records to estimate the top 10%, used 1913 data to estimate the top 1%, and backcasted these numbers to 1910.

The problem is that the estimates that Piketty (and his co-author Emmanuel Saez) produced in 1913 and 1917 are now known to significantly overestimate inequality. In the article economic journal Co-authored with Phil Magness, John Moore, and Phillip Schlosser, and related articles with Phil Magness economic survey, Fixed these errors. In fact, we showed that the entire data series from 1917 to 1962 is flawed. The reasons are how missing filers are handled, how net income is converted to adjusted gross income, and state and local governments (forgetting that 5% of employees are employers). (incomes well above the national average) were not required to file federal taxes until 1938.

They also found that Piketty and his co-authors had incorrectly estimated total income. They arbitrarily defined gross income as 80% of personal income (according to national accounts) minus transfers. They argue that “the ratio between gross income reported on tax returns and personal income net of transfers in the national accounts has remained fairly stable (about 75-80%) since the late 1940s.” Justified this. However, according to its own datasheet, the actual average was 82.7%. Although this difference may seem small, a higher ratio reduces the income distribution of the wealthy. Using a less arbitrary method, we find that the denominator is much larger, resulting in a smaller income share for the richest group.

Overall, we find that the income share of the top 10% is 5 percentage points lower than Piketty’s income share in 1917. If you use the exact same backcasting technique that Piketty did in his book, you will also get a lower percentage of your total income. to the richest 10% of Americans. When we combine this with the Lindert and Williamson estimates for 1870, we see a significant reduction in inequality, as seen in the figure below.

This has many implications. Consider that economic growth indicates that between 1870 and 1910, Americans enjoyed an average annual income increase of 1.9% to 2.0%, depending on the data series used. Never before in history had such rapid growth been observed up to that point. And when there was roughly comparable growth, it was clearly marked by rising inequality.

The bottom 90% getting a bigger piece of the pie means that the bottom 90% probably experienced a larger improvement than the average gain. Given the numbers I have, this means that the incomes of the poorest 90% have increased by 2.0-2.2% each year.

The difference is that this era, often characterized as one of increased capital concentration and inequality, actually not only experienced the fastest and most sustained growth ever observed; This also means that this was the first time in history that the incomes of the poor were increasing faster than the average. , have experienced significant improvements in their standard of living.

Modern writers of the 19th centuryth Century noted that there were exceptional profits at the bottom of the income ladder. We overlooked them, in part, because we relied on misleading data and contemporaries saw with their own eyes the true achievements of people at the lower end of the income distribution. This seems to be due to vague progress.

Vincent Geloso is an assistant professor of economics at George Mason University.