Connor says: Not at all surprising, especially if you read Lambert’s October 24th article.Biden bets on second pandemic virus: ‘Let’Er Rip’ with H5N1 (‘Bird Flu’)”It mainly dealt with cattle. The following works show that the human condition is progressing as well.

By Amy Maxmen, KFF Health News Public Health Regional Editor and Correspondent, covers efforts to prevent disease and improve well-being outside of the health care system, and the obstacles that stand in the way. It was first published in KFF Health News.

Bird flu cases have more than doubled in the country within weeks, but surveillance of human infections has been patchy for the past seven months, leading researchers to wonder why the surge is occurring. It has not been determined whether there are any.

Just this week, California reported 15th infection Dairy workers and Washington state reported seven probable cases among poultry workers.

Hundreds of emails from state and local health officials obtained through records requests from KFF Health News help explain why. Despite health authorities’ strenuous efforts to track human infections, surveillance is marred by delays, inconsistencies, and blind spots.

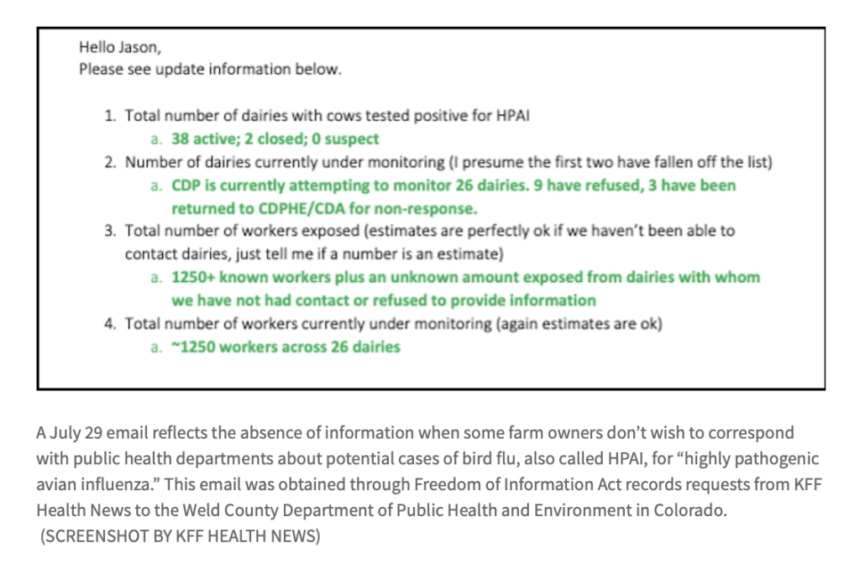

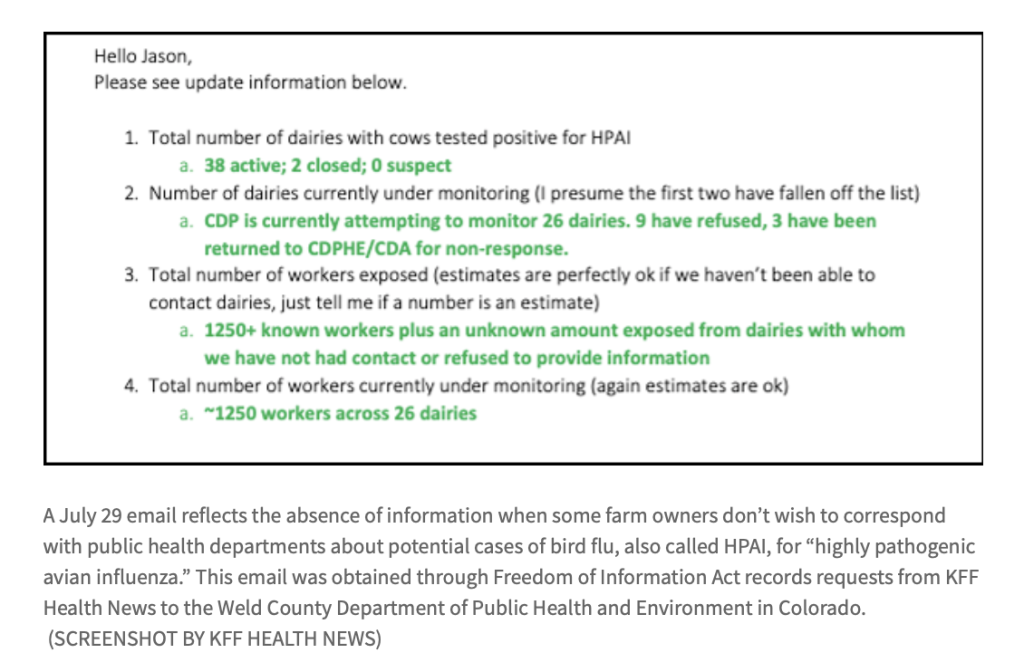

Some documents reflect a breakdown in communication with some farmers who do not want to have themselves or their employees monitored for signs of bird flu.

For example, a terse July 29 email from Colorado’s Weld County Department of Public Health and Environment states, “We are currently attempting to monitor 26 dairy farms. Nine have declined.”

The email included a tally of people on farms in the state that were being monitored, including “more than 1,250 known workers, plus those from dairy farms who had no contact or declined to provide information. “This includes an unknown amount of exposure.”

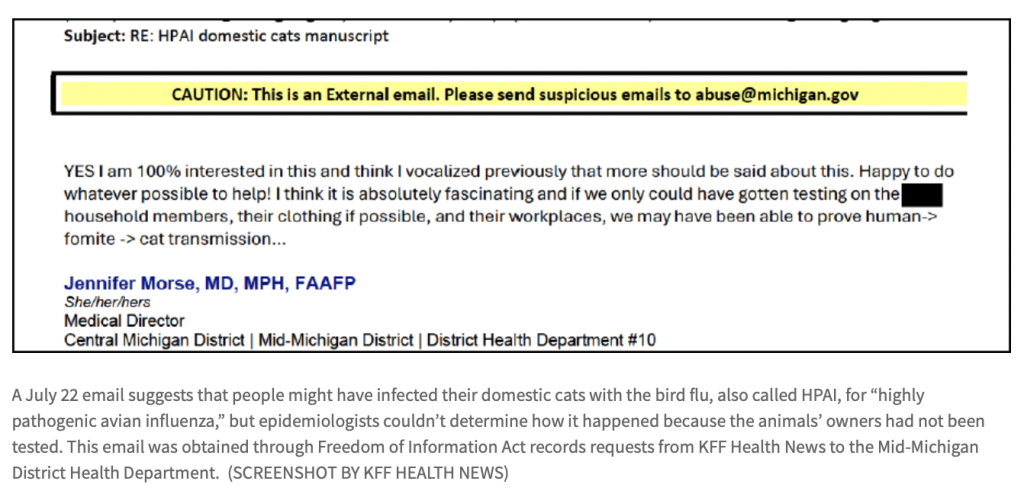

Other emails suggest cases at dairy farms were missed. Correspondence between health officials in Michigan also suggested that people associated with dairy farms spread the avian influenza virus to domestic cats. But there wasn’t enough testing done to really know.

Researchers around the world are growing concerned.

“The lack of epidemiological data and the lack of surveillance bothers me and worries me,” said Nicole Lurie, former assistant secretary for preparedness and response in the Obama administration.

Avian influenza viruses have long been on the list of potential pathogens. Possibility of pandemic. Although the virus has been present in birds for nearly 30 years, the unprecedented spread among U.S. dairy cows this year is alarming. Viruses have evolved to multiply inside mammals. “We need to further consider systematic and strategic testing in humans,” said Maria van Kerkhove, head of the World Health Organization’s emerging diseases division.

Rejection and delay

A key reason for the disparity in surveillance is that the majority of public health decisions are made on cows, according to emails, slide decks, videos, and interviews with health officials in five states obtained by KFF Health News. It is up to the farm owner who reported the outbreak among poultry or poultry. occurrence.

In a video of a small meeting at the Central District Health Department in Boise, Idaho, an official told colleagues that some dairy manufacturers would like to disclose their names and locations to the health department. I warned you that this is not the case. “In places like that, our involvement becomes very vague,” she said.

“We just finished speaking with the owner of the dairy farm,” a public health nurse with the Mid-Michigan District Health Department wrote in a May 10 email. “(REDACTED) I have a feeling this may have started (REDACTED) a few weeks ago. That was the first time they noticed a decrease in milk production,” she wrote. “(Redacted) does not feel he needs an extension from MSU to come out,” she added, referring to the support provided to farm workers by Michigan State University.

“Multiple dairy farms have declined on-site visits,” the Weld, Colorado, infectious disease program manager wrote in a July 2 email.

Many farmers cooperated with health authorities, but delays between visits and outbreaks meant cases could have been missed. “Four individuals discussed having symptoms” of visiting a farm with an avian influenza outbreak, Weld health officials wrote in a separate email. “Unfortunately, all of them were either already past their testing period or did not want to be tested.” ”

Jason Cheshire, head of public health at Weld, said farmers often tell them not to visit due to time constraints.

Dairy farming requires labor throughout the day, especially when the cows are sick. When employees pause work to learn about the avian influenza virus or get tested, it can reduce milk production and harm animals that require attention. Additionally, if a bird flu test is positive, farm owners may lose several more days of work and workers may not receive a paycheck. Several health officials said this reality complicates public health efforts.

An email from Weld’s health department regarding Colorado dairy farmers reflected this idea. “Producers are refusing to send their employees to Sunrise (clinic) to get tested because they are too busy. He also has pink eye.” Conjunctivitis is a disease caused by a variety of infections, including bird flu. This is a symptom of

Chesher and other health officials told KFF Health News that instead of visiting farms, they often ask owners and supervisors to let them know if someone on their property becomes sick. Or they might ask farm owners for a list of employee phone numbers and encourage employees to text the health department about symptoms.

Jennifer Morse, medical director for the Mid-Michigan Health Department, acknowledged that relying on pet owners could lead to missing high-risk cases, but that being too pushy could reignite a public health backlash. Some of the fiercest resistance to COVID-19 measures include: masking and vaccinewas in the countryside.

“It’s better to understand where they’re coming from and figure out the best way to work with them,” she said. “Because if you try to go against them, it won’t work.”

cat clue

And there was also a pet cat. Unlike dozens of stray cat These domestic cats, found dead on infected farms, did not roam around the herd or swallow virus-laden milk.

In an email, Mid-Michigan health officials hypothesized that the cat may have contracted the virus from droplets called “fomites” on its owner’s hands or clothing. The email, dated July 22, said: “If we could have inspected (redacted) household members, their clothing if possible, and their workplaces, we might have been able to prove human-to-fomite-to-cat transmission.” It was written.

Her colleagues suggested publishing a report on cat cases “to inform others about the possibility of indirect infection of companion animals.”

Thys Kuijken, a Dutch avian influenza researcher at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, said felines are highly susceptible to the virus, so transmission from humans to cats is not surprising. It could be caused by fomites, he suggested, or an infected but untested owner could have passed it on.

Hints about missed incidents further increase mounts Evidence of undetected avian influenza infection. Health officials said they were aware of the problem but that it was not solely due to opposition from farm owners.

Local health departments are chronically understaffed. In rural areas, there is one public health nurse for every 6,000 people, but these nurses often work part-time. one analysis Found it.

“State and local public health departments are resource-strapped,” Lurie said. He currently serves as the executive director of the international organization Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. “You can’t expect them to do their job if you only provide resources when there’s a crisis.”

Another explanation is that there is a lack of urgency because the virus has not seriously affected the country this year. “If hundreds of workers had died, we would have increased our oversight of workers,” Cheshire said. “However, a small number of mild symptoms do not require drastic action.”

All cases of avian influenza in U.S. farmworkers presented with conjunctivitis, cough, fever, and other flu-like symptoms and resolved without hospitalization. But infectious disease researchers say the numbers are too low to draw conclusions, especially given the virus’ tragic history.

about half 912 people A man who had been diagnosed with bird flu for more than 30 years has died. Many cases probably went undetected because the virus changes over time. However, Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Brown University Pandemic Center, said that even if the actual number of people infected (the denominator) was five times higher, if the avian influenza virus evolved and spread rapidly between 2018 and 2020, He said the mortality rate would be a catastrophic 10%. people. The fatality rate for the new coronavirus infection was approximately 1%.

Missing infected people could delay public health systems from noticing if the virus becomes more transmissible. Delays already meant that cases of possible human-to-human transmission were missed in early September. After a hospitalized patient in Missouri tested positive for the avian influenza virus, public health officials learned that a person in the patient’s home had become ill and recovered. It was too late to test for the virus, but on October 24, the CDC announced that an analysis of the person’s blood found antibodies to bird flu, a sign of previous infection.

CDC Principal Deputy Director Nirav Shah suggested that the two people in Missouri may have been infected separately, rather than passing the virus from one to the other. But it’s impossible to know for sure without testing.

As flu season begins, the likelihood of more contagious variants emerging increases. When infected with avian influenza and seasonal influenza at the same time, the two viruses can exchange genes and form a hybrid, which can spread rapidly. “We need to take steps today to prevent the worst-case scenario,” Nuzzo said.

The CDC can directly monitor farmworkers only at the request of state health officials. But the agency is tasked with providing a complete picture of what’s happening nationally.

As of October 24th, CDC Dashboard It says more than 5,100 people are being monitored across the country after being exposed to sick animals. Over 260 were tested. 30 cases of avian influenza were detected. (The dashboard has not yet been updated and includes the latest cases and five reports from Washington state pending confirmation from the CDC.)

Van Kerkhove and other pandemic experts said they were perplexed by the lack of detail in the agency’s latest information. The dashboard breaks down numbers by state and monitors health officials through daily updates via visits and texts, or a single call with a busy farmer distracted by sick cows. No breakdown of the number of people was given. It was not disclosed how many workers in each state were tested or how many farm workers refused contact.

“We’re not being provided enough information and enough transparency about where these numbers are coming from,” said Samuel Scarpino, an epidemiologist who specializes in disease surveillance. The number of avian influenza cases detected doesn’t mean much unless you know the proportion, or the rate of infection among workers.

This makes California’s increase puzzling. Without a baseline, the state’s rapid increase could mean it is testing more aggressively than other regions. Alternatively, the spike could indicate the virus is becoming more contagious. Although unlikely, this is a very worrying development.

The CDC declined to comment on concerns about surveillance. On October 4, Shah briefed reporters on the outbreak in California. He said the infected cases were identified because the state is actively tracking farmworkers. “This is public health in action,” he added.

Salvador Sandoval, a physician and county health officer in Merced, California, did not exude such confidence. As cases increase in the region, “surveillance is not ongoing”, he said. “It’s a really worrying situation.”