At a recent bloggers’ conference, I was asked to name the most important paper published in my field (macroeconomics) in the last 10 years. I couldn’t think of any.

In some ways, it reflects the fact that the field has moved on from the 20th century macro studies with which I am most familiar. My ignorance may say more about me than it does about the field. In my despair, I turned to Paul Krugman’s 1998 Brookings Institution paperI came back I remember “… . . . ” as a recent paper that had a decisive influence on our thinking about macroeconomics. A few years ago, I wrote a paper arguing that it was heavily influenced by the important “Princeton School” of financial economics.

Many brilliant economists continue to do very sophisticated work in the monetary/macro field. But I rarely come across a new paper that seems interesting to me, at least in the same way that I found many late 20th century papers interesting when they were first published. And it’s not just macro. A general art fan like me is familiar with hundreds of famous paintings from 1880 to 1924, but knows very few famous paintings from 1980 to 2024. Why is that?

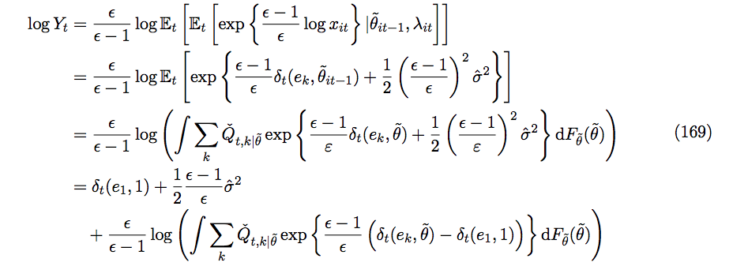

Tyler Cowen Recently linked to an NBER working paper Joel P. Flynn and Kartik Sastrikslooks at how optimistic and pessimistic narratives affect business cycles. On a technical level, this 134-page paper is far more sophisticated than anything I’ve ever written, using literally hundreds of formulas, some of them quite complex. Here’s an excerpt from the conclusion:

After calibrating our model to the data, we find that narratives’ business cycle effects are quantitatively significant: the decline in measured optimism accounts for about 32% of the peak-to-trough decline in output during the early 2000s recession and 18% during the Great Recession. Finally, we show that the interaction of many simultaneously evolving and highly contagious narratives (some of which are individually prone to hysteresis) may nevertheless underlie stable fluctuations in emergent optimism and output. Taken together, our analysis indicates that narratives may be an important source of business cycles.

Their work employs a “real business cycle” framework, which I am generally somewhat skeptical of: It’s not that these RBC models don’t tell us important things about the economy, but rather I believe that (at least in the US) real business shocks are the primary determinant of long-term trends, not business cycles (with COVID being the notable exception).

I only skimmed the paper, so I won’t comment on their empirical estimates, but the following caught my eye:

Our analysis leaves at least two important areas open for future research. First, we analyzed how corporate narratives matter, abstracting from studies of household narratives. It stands to reason that similar mechanisms may be at work on the household side of the economy, where contagious narratives may influence spending and investment decisions. Moreover, co-evolving narratives on both the “supply” and “demand” sides of the economy may have mutually reinforcing effects. From this perspective, narratives may explain business cycles more than our analysis suggests.

I like this view because I have long believed that the most important impact of a supply (real) shock is how it interacts with a demand (nominal) shock. So the 2007 housing/banking real shock likely depressed the natural rate of interest. The Fed lagged and cut rates too late (especially in 2008). This lowered nominal GDP (reduced demand) and made the recession even worse.

They conclude with a near-mandatory call for further research.

Second, there is still much to be done about “what makes a story a story” – in the terms of our model, the microfoundations of a set of stories and their contagion. Studying these issues in greater depth could shed additional light on policy issues, such as the interplay of stories with standard macroeconomic policies, and the potential impact of “managing stories” directly through communication. Moreover, exploring the deeper origins of stories could further enrich research on story ensembles beyond our analysis and provide a fuller account of the economic, semantic, and psychological interactions between stories in a complex world.

Will follow-up studies answer these questions? I am skeptical. I worry that the next couple of bright young macroeconomists will think, “Flynn and Sastrix have already done it, let’s develop another model.” There is probably enough truth in almost any plausible macro model that we can find empirical support for the theory (at least, if we “torture” the dataset enough).

My skepticism of modern macro may simply be the result of being an old man out of touch with current trends, and I think that’s true. But in the late 20th century, you didn’t need to read a 100-page research paper to understand that macro was producing a lot of innovative ideas. I just didn’t see any interesting new ideas explained in non-technical papers aimed at the layman.

Here’s one way to think about my pessimistic thinking: I’ve studied macroeconomics almost my entire life. I came to the conclusion fairly early on that US business cycles are very simple. For the most part (outside of the COVID-19 pandemic), it was just a matter of monetary policy errors causing fluctuations in NGDP and real GDP being highly correlated in the short run due to wage rigidities.

To explain why paintings from 1880-1924 are more memorable than those from 1980-2024, one might point to the fact that there were not so many interesting new styles to discover in the latter period, whereas painters from the earlier period discovered many interesting new styles. Another way of looking at it is that I am wrong and future generations will discover even more masterpieces of pictorial art from the period 1980-2024 than they did 100 years ago. Only time will tell.

Thomas Kuhn said that science often makes progress by developing a model, discovering an “anomaly” that the model cannot explain, and then developing a new, improved model to explain the anomaly. Probably the best macro models of the late 20th century explain business cycles pretty well (and the “Fed mistake” theory I just described explains why). Description does not imply prediction). Perhaps the remaining anomalies are simply too difficult to explain.

But this doesn’t fully explain my skepticism towards modern macro. Too many A lot of great macro models have emerged in the second half of the 20th century: Keynesian, monetarist, real cycle, Austrian, MMT, and many more, with many variations within each category. Flynn and Sastrix adopt the RBC framework in their paper. From the outside, this line of analysis seems a bit off-base, as I personally don’t think this framework is particularly useful for understanding business cycles. And that skepticism doesn’t just apply to the RBC model. Any Non-market monetarist models somehow miss the point: they all seem to be trying to explain what is already well explained: they don’t address the anomalies in their models where Fed mistakes drive up NGDP, wage rigidities create cycles, and they usually work with a completely different framework.

So for a grumpy old man like me, macros are no longer progressiveWe’re not trying to fill the gaps, we’re always trying to reinvent the wheel.

Again, I could very well be way off the mark, but all I can say is that I no longer read a paper and think, “I’ve always wondered why certain macro variables (M, Y, P, i, U, etc.) show this pattern, and now it makes more sense.” I don’t feel like I’m making progress.

However, people in 1890 hadn’t yet realised how great Van Gogh was, so it’s entirely possible that I’m missing something important.

P.S.: This is a Kandinsky painting from 1925. What else was I supposed to say?

PPS. Below is one of the 247 formulas in the paper.