Hi, I’m Eve. You’re posting this article despite the authors having absolutely no justification for censorship, and especially no consideration of the deep-rooted contradiction of portraying censorship as a bastion of democracy. This attitude shows once again how scared the ruling cliques in Western countries are, and how they rely too much on message, rather than gaining legitimacy from delivering concrete material benefits to their people and competently running bureaucracies that meet often conflicting demands as fairly and efficiently as possible.

Admittedly, the author is Swiss, and freedom of speech is generally not (historically, at least) central to the exercise of democratic rights in Europe, but it seems noteworthy that this trend suggests that the US, perhaps deliberately, has not promoted this key element of US democracy through “democracy” promotion agencies such as the National Endowment for Democracy or Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

I trust that readers will enjoy criticizing this article.

By Marcel Kesmann (PhD student in Economics, University of Zurich), Jannis Goldsicher (PhD student, University of Zurich), Matteo Grigoletto (PhD student, University of Bern, PhD student, Wies Academy of Natural Sciences), and Lorenz Gschwendt (PhD student, University of Duisburg-Essen). Vox EU

Many democracies have begun to worry about the spread of propaganda, misinformation, and biased discourse, especially on social media. This paper examines the EU’s ban of Russian state-run media outlets following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and examines whether censorship has curbed the spread of biased discourse. While the ban did indeed reduce pro-Russian bias on social media, its effect was short-lived. Increased activity of other providers of biased content not subject to the ban may play a role in mitigating the effects of the ban. Regulation in the context of social media, where many players can create and spread content, poses new challenges for democracies.

Misinformation, propaganda, and biased narratives are increasingly recognized as major concerns and sources of risk in the 21st century (World Economic Forum 2024). Russia’s interference in the 2016 US presidential election marked a key moment in raising awareness of foreign influence in the democratic process. From Russia’s “asymmetric war” in Ukraine to China’s influence on TikTok, authoritarian regimes are weaponizing information and shifting efforts from outright repression to narrative control (Treisman and Guriev 2015, Guriev and Treisman 2022).

Recent studies (Guriev et al. 2023a, 2023b) highlight two main policy options that democracies can adopt to counter this threat. One strategy relies on top-down regulatory measures to control foreign media influence and the spread of misinformation. The other addresses the problem at the individual level using media literacy campaigns, fact-checking tools, behavioral interventions, and similar measures. The first approach is particularly difficult to implement in democratic contexts because of the inherent trade-off between implementing effective measures to curb misinformation and preserving freedom of speech as a core principle of the democratic order.

Recent measures such as the Protecting American Persons from Foreign Adversarial Control Applications Act passed by the US Congress in 2024, the EU’s Digital Services Act (European Union 2023), Germany’s NetzDG (Müller et al. 2022; Jiménez Durán et al. 2024), or Israel’s ban on Al Jazeera broadcasting activities show that democratic governments consider large-scale policy interventions a necessary and viable tool to counter the spread of misinformation. At the same time, the growing importance of social media as a news source adds new complexities to effective regulation. In contrast to traditional media such as newspapers, radio, and television, which have a limited number of senders, social media are characterized by a large number of users who act as producers, disseminators, and consumers of information, making the flow of information more difficult to control as their roles change in a fluid manner (Campante et al. 2023).

To shed light on the impact of censorship in democracies, our recent study (Caesmann et al. 2024) examines the EU ban on Russian state-run media outlets Russia Today and Sputnik. The EU implemented the ban on March 2, 2022 to prevent the spread of Russian narrative in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The unprecedented decision to ban all activity of Russia Today and Sputnik was implemented virtually overnight and affected all channels, including online platforms.

We investigate the effectiveness of the bans in shifting conversation away from pro-Russian government bias and misinformation narratives on Twitter (now X) among European users. To do this, we exploit the fact that the bans of Russia Today and Sputnik were implemented in the EU, while similar measures were not taken in non-EU European countries such as Switzerland and the UK.

Media bias regarding war

We build on recent advances in natural language processing (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2011; Gennaro and Ash 2023) to measure each user’s opinion on the war by assessing their proximity to two narrative poles: pro-Russia and pro-Ukrainian. We create these poles by analyzing over 15,000 tweets from accounts associated with the Ukrainian and Russian governments. Using advanced natural language processing, we convert these tweets into vectors that represent the average positions of pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian government tweets. We use these as the two polarized poles of Twitter conversations about the war.

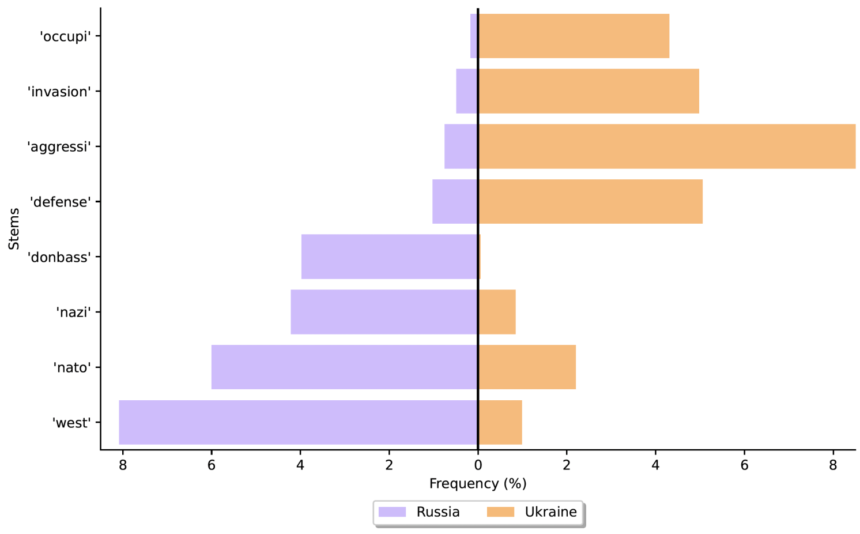

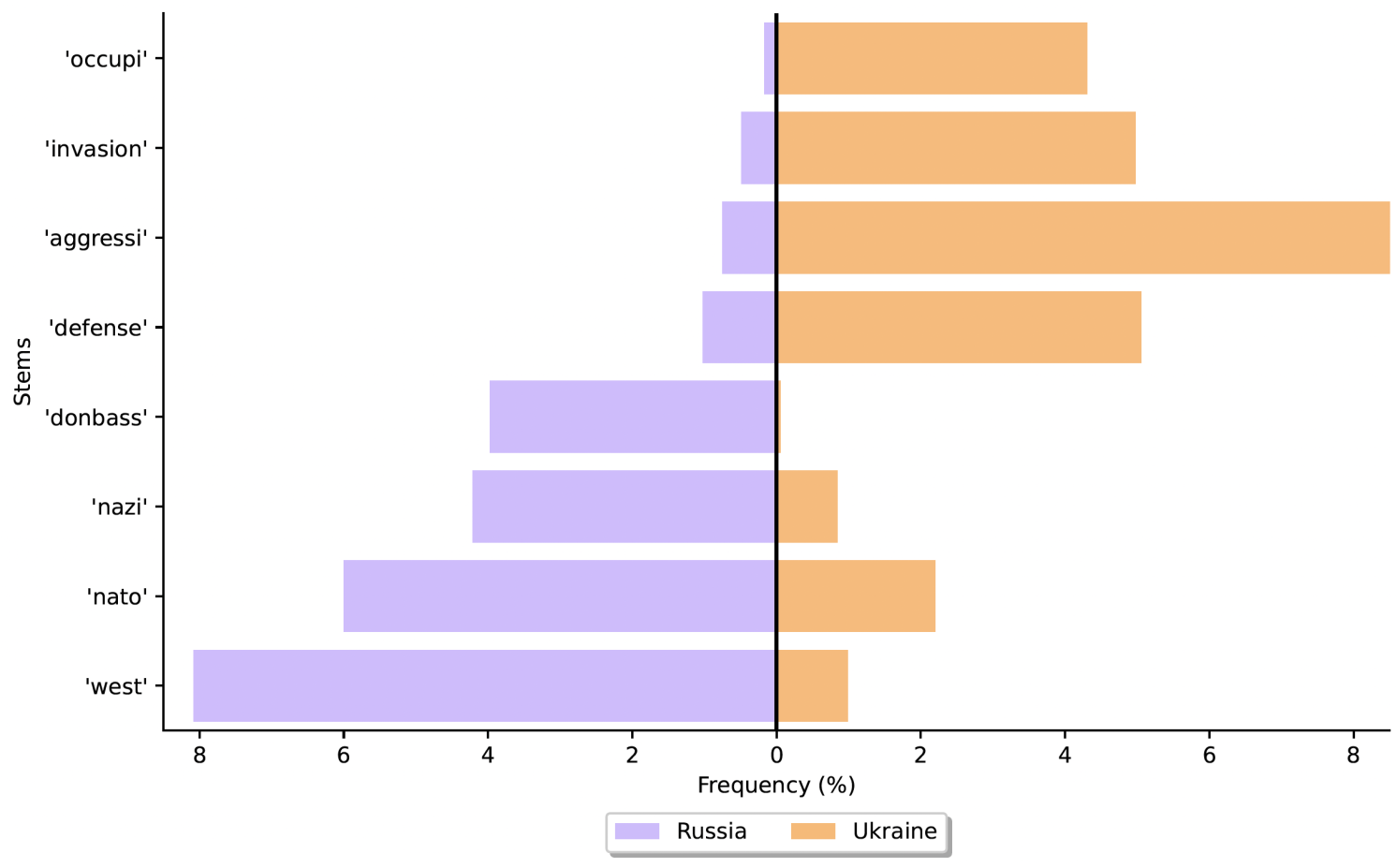

Figure 1 shows the differences in content between government tweets, with keyword frequency in Russian government tweets in purple (left) and Ukrainian government tweets in orange (right). Keywords such as “attack” and “invasion” are primarily used by Ukrainian accounts to portray the conflict as an invasion, while Russian stories refer to it as a “military operation.” Other keywords such as “occupation,” “defense,” “NATO,” “West,” “Nazis,” and “Donbass” further highlight the differences in each side’s narrative. These terms highlight the bias of government content and therefore are an effective benchmark for measurement.

Figure 1 Word frequency in a sample of government tweets

Note: Russian government tweets are in purple (left) and Ukrainian government tweets are in orange (right).

We then collect over 750,000 tweets about the conflict in the four weeks before and after the ban was implemented. We calculate the tilt of each tweet by calculating its proximity to the Russian pole relative to the Ukrainian pole and centering it at zero. This metric is negative if the tweet is tilted toward the Ukrainian pole and positive if it is tilted toward the Russian pole.

Censorship to protect democracy

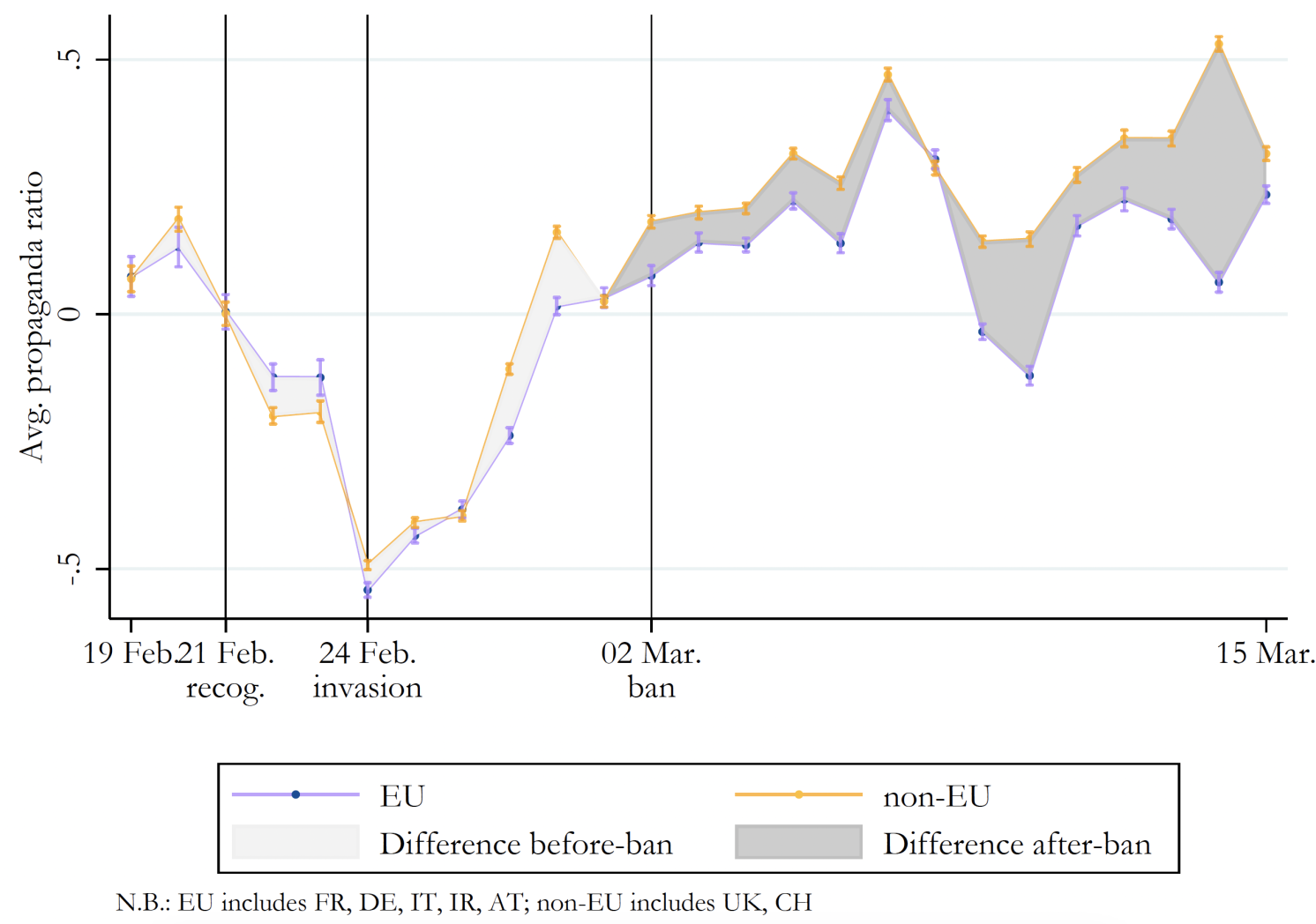

Figure 2 plots the average time series of raw data on average trends by users in countries affected by the ban (blue) and those not affected by it (orange). The media trends measure captures the dynamics of online discussions. Until the invasion, the conversation was moving towards the pro-Ukrainian pole. The start of the invasion coincided with a rise in pro-Russian activity and likely captures the intense online campaign that flooded Europe and forced the EU to act quickly. Overall, the raw data already shows the impact of the ban on the spread of pro-Russian government content. We can see that the divergence between the average trends of EU and non-EU countries widened after the implementation of the ban.

Figure 2 Tilt measurement time series: daily average

To estimate the causal effect of the ban more systematically, we use a difference-in-differences strategy to compare users in EU countries affected by the ban (Austria, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy) with users in non-EU countries (Switzerland, UK) that were not affected by the ban at the time of the survey.

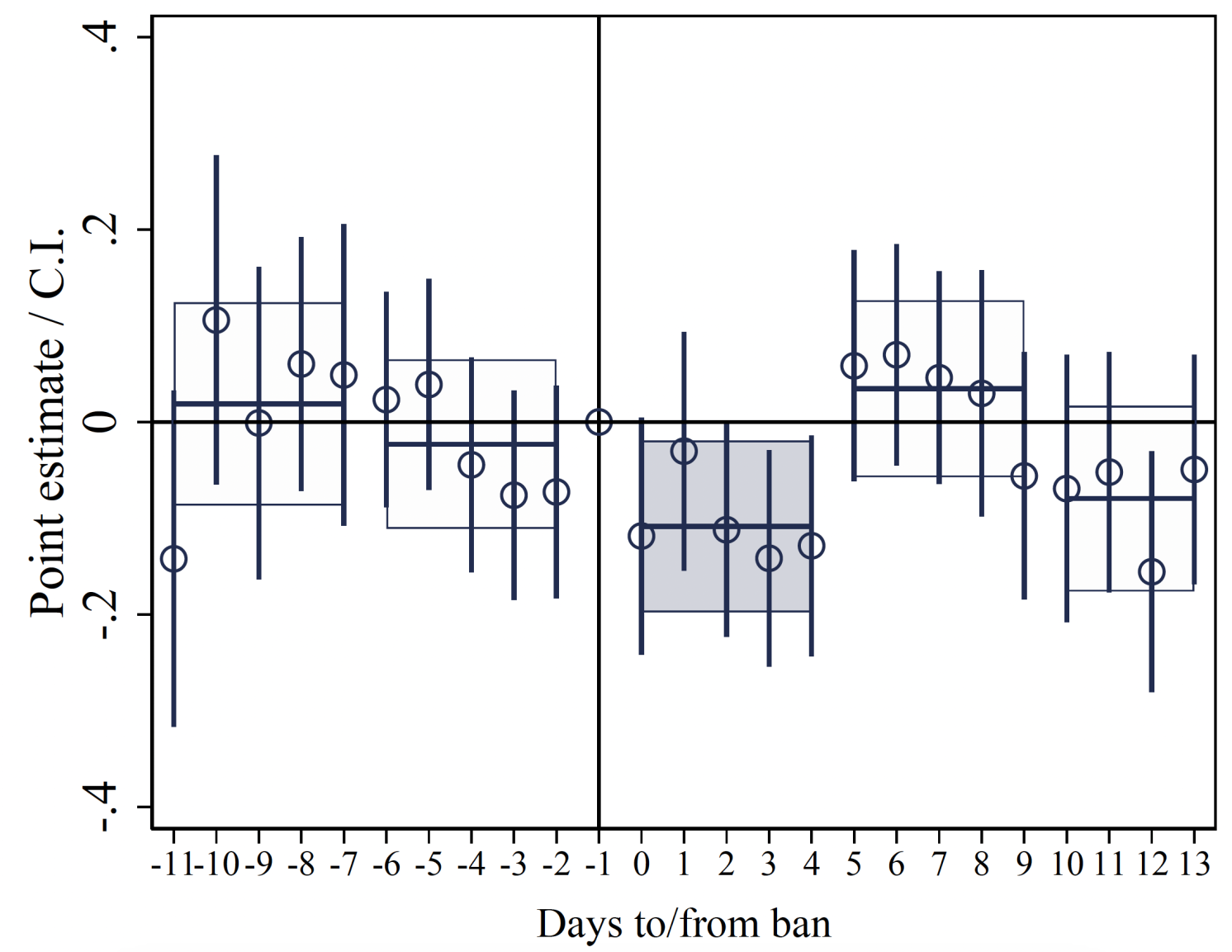

First, we focus on users who previously interacted directly with the two banned media outlets (following, retweeting, replying). Figure 3 shows the results of this analysis, showing that the ban had an immediate and significant effect on reducing the pro-Russian tendencies of users affected by the policy. According to our estimates, the ban reduced the average tendencies of users who had these interactions by 63.1% compared to the pre-ban average, whereas there was no clear tendency before the ban. The paper shows that this effect is most pronounced among users who were the most extreme before the ban.

Figure 3 Daily Event Survey in Our Tilt Measurement: Interaction Users

Is censorship a viable policy tool?

A closer look at the temporary impact of bans suggests that their impact fades over time: there is an impact immediately after the ban, but even within the short-term scope of our study, the difference in the average slopes between users affected and unaffected by the ban closes within a few days after its implementation.

We also looked at the indirect effects of the ban on users who did not directly access banned media, and found that the ban also reduced pro-Russian leanings. Non-Interacting UsersHowever, this occurred to a lesser extent, amounting to a decrease of about 17.3% from pre-ban slope levels, as opposed to a decrease of 63.1%. Interacting UsersNotably, we find a decline in the proportion of pro-Russia retweets that drive this effect, a finding that suggests the ban is depriving Russia supporters of benefits. Non-Interacting Users They are able and willing to share even biased content.

Our findings suggest that the bans had an immediate impact, especially on users who had interacted with banned outlets before the bans were implemented. However, this effect fades quickly and has limited impact on indirectly affected users.

In the final stage of the analysis, we explore the mechanisms that may have compensated for the effects of the ban and effectively rebalanced the supply of pro-Russian content. In particular, this study examines: supplier Ban on biased content. We provide evidence suggesting that the most active providers increased their production of new pro-Russian content in response to the ban, thereby helping to counteract the overall effect of the ban.

By studying the effects of a larger policy alternative: government media censorship, our analysis complements insights from studies that have explored smaller policy interventions targeted at individual users (Guriev, Marquis et al. 2023; Guriev, Henry et al. 2023). Specifically, we provide evidence that censorship in democratic contexts can affect content circulating on social media. However, the effectiveness of such measures appears to be limited, reflected in the short-term effects of bans and limited impact on users who are only indirectly affected by the policy.

Our study points to the important role of other providers filling the void created by censorship of core media. This reflects the changing nature of media regulation in the context of social media, where many users can create and disseminate information at low cost. The ability and willingness of other users to act appears to limit the effectiveness of large-scale regulatory measures targeting major media outlets. Successful policy interventions need to take into account these limitations of large-scale regulatory measures in the context of social media.

look Original Post References