Lambert: carpe diem…….

The authors are Jamie Bristow, who currently leads public narrative and policy development for Inner Development Goals, and Rosie Bellon, who writes primarily about public climate narratives and the inner dimensions of sustainability, with collaborators including the Climate Majority Project, the Life Itself Institute and the Mindfulness Initiative. Originally published on DesmogBlog.

As the drama of climate breakdown intensifies, especially as we approach the 1.5°C threshold, a dichotomy has emerged that consumes enormous amounts of time, energy and passion, and unnecessarily limits the vision to confront and adapt at all levels of society: Are we (optimistic) solvers or (realistic) pessimists?

As “optimists”, we are committed to the idea that it is not too late to improve the situation (think of the increasingly rough path to net-zero that relies on direct air capture). As “realists”, we are committed to telling the “truth” of how bad the situation is already (think of cascading tipping points and the trajectory to a Hothouse Earth).

Both positions are well-intentioned and are easier to define by harshly criticizing the other. To the optimist, the realist is the pessimist. He spreads demoralizing despair and self-fulfilling prophecies, often with unfounded certainty. If it is already too late to solve the problem, why make an effort? From this perspective, “accepting” the possibility of crossing the 1.5°C red line is a betrayal to those who will feel its effects most harshly. To the realist, the optimist is a naive solutionist. He traps the public in a dangerous fantasy world where incremental changes will be enough, leaving our consumerist lifestyles more or less intact. Trusting that smart people somewhere will solve everything (and they will at the last minute), we remain passive bystanders while the crisis escalates beyond our ability to intervene. According to this explanation, optimism is itself a betrayal, preventing the public from accepting that radical changes are necessary to protect the most vulnerable.

Both criticisms have a point. Optimists point to compelling psychological evidence about the demotivating effect of bad news. Realists bring in common sense. How can we expect people to support sufficiently radical climate action, with all the sacrifices and trade-offs, if they don’t know the true scale of the problem? In fact, nearly all of the experts involved value both hope and realism, and think they’ve got the balance right between the two (and, rest assured, no one’s opinion is as simple as we paint it here). But these respective strategies and communication frames come across as adversarial and tend to be paralyzing. Citizens looking for channels for their awakening climate anxiety are caught between two imperatives: to doubt optimism for fear of complacency, or to ignore how bad the situation is already for fear of despair.

Certainly, neither despair nor complacency will do us any good. both Acceptance and optimism are functional necessities. Acceptance of the current situation is a prerequisite for effective action in the reality in which we live, and the hope that a livable future is possible is a prerequisite for the efforts necessary to make it a reality. Rather than strategizing by opposing one set of values against the other, what is needed is a middle way, where hope is paramount, but what we want is to be able to live in a world that is not ours. for It is allowed to evolve in line with current realities and the different ways things might unfold.

Adaptive challenges and opportunities for change

Between total, miracle solutions and total, environmentally induced societal collapse, there are a wide range of middle-way possibilities. None are better than addressing the climate crisis 30 years ago at a cost of just 2% of GDP. Both are deeply tragic in contrast to the dreams of technological solutions. Absent a sudden, global epiphany, we will not be able to avoid loss and disruption on a scale that is incomprehensible given the current circumstances. Millions, perhaps billions, of people will lose their livelihoods and homes, or worse. Meanwhile, the current rapid declines in biodiversity and wild biomass will increasingly veer into localized ecosystem collapse and even mass extinction. The brighter of these paths, however, promise a worthy future for many people around the world, a future that is much brighter in the long run. And crucially, to realise those possibilities, even a small degree of avoidable warming will be crucial. The scope of our optimistic imagination must therefore be kept wide, and we should be humble about what we can know for sure.

It is incumbent on all of us never to downplay future human suffering, especially that of those on the front lines of climate impacts, but it is equally incumbent on us to consider whether even catastrophic scenarios contain the seeds of necessary regeneration, both in the medium term and on a civilization-wide scale.

Our environmental crisis is no accident. way of thinking — a mindset that continues to exhibit destructive patterns for humanity and all life on Earth, and will continue to do so until we are forced to confront it. Separation The economic “externalities” that underpin global institutions and industries allow invisible costs of pollution and exploitation to disappear from balance sheets and moral considerations. But in reality, interconnected global ecosystems have no externalities. That’s why the climate crisis is “The danger of disconnection” Or, more specifically, in the dominant culture. Perceive Understand our connections to the rest of the world and act accordingly. The same mentality of separation that underpinned centuries of colonialism and exploitation is at the root of today’s global inequality, social marginalization, and uncontrollable ecological destruction. We face more than just technological or material problems. Adaptation TaskMany of us will need to rethink our approach to problem-solving and adopt entirely new ways of thinking. A desirable future will depend on changing not only our behaviors, but also our perceptions and values – our general ways of looking at the world. And collective mindsets can and do change, especially in times of crisis.

Humanity is not yet evolved enough to recognize an abstract, diffuse, long-term threat like global warming as a call for fundamental change. But as climate impacts become more concrete and immediate, dominant cultures will be forced to transform in ways previously unimaginable. This could be the catalyst for a widespread shift in thinking, as many experts believe that without a major course correction, severe crisis and the collapse of fragile Earth systems are likely within just a decade or two.

We do not wish this upon ourselves. A severe crisis would mean massive loss of life, the collapse of critical infrastructure, and the breakdown of social cohesion, greatly increasing the risk of cascading collapse and authoritarian rule. We must therefore do all we can to make our societies more resilient. But such a scenario may also contain an opportunity to foster a collective worldview that is attuned to reality, to embrace our close interdependence, and to foster a culture of repair, regeneration, and renewal. Such a shift in collective thinking, whenever possible, would transform our attitudes toward ecology as well as a series of simultaneous crises of alienation, inequality, materialism, and nihilism, limiting harm in the short term and laying the foundations for a radically better future. This is the kind of hope that will last well beyond our lifetimes. It is a difficult task in an individualistic age, but on the flip side, the sooner we can anticipate such a shift, the sooner we can move away from the dualism of solutionism and pessimism and the more likely we are to stay on the collapse curve. As shallow as possible.

Three areas of activity

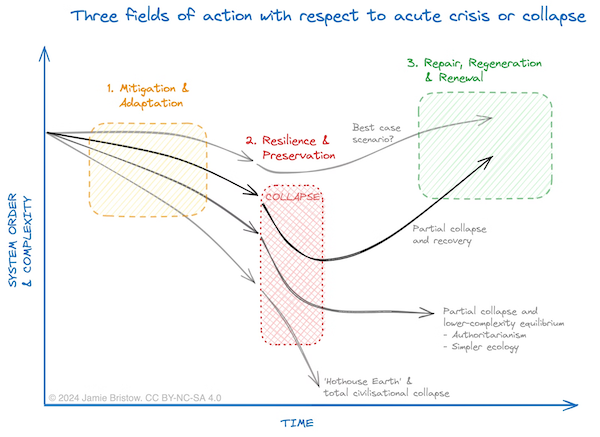

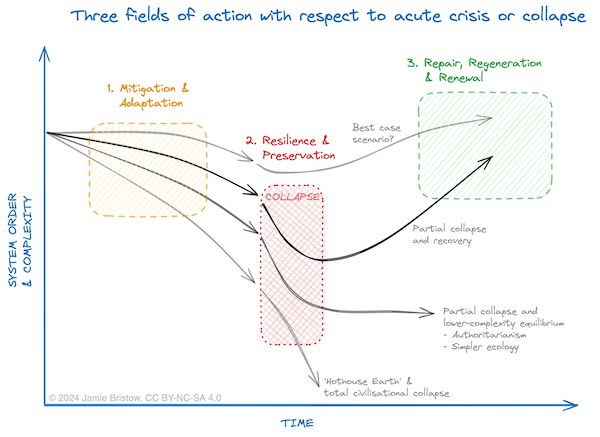

As we hopefully contemplate this broad field of a future yet to be determined, we might imagine three interrelated “areas of action” that require our energy and commitment.

1. Immediate mitigation and adaptation

We must avert the worst impacts of climate change through ambitious collective action to reduce emissions and limit the destruction of ecosystems. Every tonne of carbon dioxide and every degree of temperature rise matters. The higher the temperature, the more true this becomes. And in the short term, we need to adapt to environmental changes, and countries most vulnerable to climate impacts are supported. Most of the discussion on climate change so far has been in this first area.

2. Resilience to future shocks

We can take action now to prepare for a severe crisis or partial collapse of the system in the medium term, preserving (some of) what is valuable and ensuring that our critical infrastructure, communities, and social order are resilient enough to withstand a major shock.

3. Foundations for future revitalization

Philosophies and practices that can be the foundation of a regenerative society may find more fertile ground in the post-crisis shift in thinking. We have an opportunity now to nurture existing wisdom, develop new ideas and approaches, and build “islands of coherence” that can serve as the seeds for a later rebirth of our civilization.

A call to action in all three areas

Efforts in these three areas each support efforts in the others, and focusing on one area does not take energy away from the others. Rather, many virtuous cycles persist between the three areas. For example, increased attention to preparing for future shocks is likely to increase public awareness and willingness to take climate change mitigation measures, and vice versa. Investing in community resilience can encourage a shift in thinking toward reducing unsustainable behaviors and a deeper understanding of our interconnectedness. Advocating for a paradigm shift can galvanize the case for radical mitigation and adaptation. Shared efforts to reduce emissions, protect local ecosystems, and build adaptive infrastructure can strengthen community ties, which in turn can support social order and sustain life in a crisis. The greater the effort we invest in all three areas now, the shallower the decline we experience and the greater the chances of regeneration.

The complex crisis we face demands that we go beyond blanket attitudes of optimism and realism. We must embrace a more nuanced understanding that incorporates a range of adaptation strategies and actions. This model is not seen as a new, fixed framework for the way things should be, but as a way to loosen our thinking about the challenges ahead. The reality is much more messy and less clearly defined than this picture suggests. But in this mess, some loss and suffering are inevitable, and we can work to minimize the impact. and Prepare for a more resilient and beautiful future.