This week is Naked Capitalism’s fundraising week. We’ve already had 141 donors invest in our efforts to fight corruption and predation, especially in the financial sector. Join us! Donation pageHere’s how to donate by check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Why are we doing this fundraiser?, What we accomplished last yearAnd our current goal is to Strengthening IT infrastructure.

Hi, Yves. There is a very important finding in the post below: the damage from deindustrialization is permanent, spreads across generations, and affects even those who are able to relocate. This shows the social costs of outsourcing and offshoring on health and income potential. This finding is particularly shocking because, as I have explained for years, the financial case for offshoring is often weak for many companies, with little consideration given to costs such as loss of know-how and increased business risk. Several public company executives have told me that they went ahead with offshoring plans even in the face of unconvincing projections, because they knew the announcement would boost their share prices.

Also, remember that this study looked at coal mining, an industry notoriously hard and unhealthy. But in Britain these were union jobs, or at least union jobs. I was in London on a long-term assignment when the Thatcher government was waging its ultimately successful campaign to dismantle the coal miners’ union. It was front-page news almost every day.

The authors conclude that the shock of the pits’ closure had a huge, negative impact on the children’s lives, yet our supposed superiors offer flippant responses along the lines of “just feed them the training.”

The study was written by Assistant Professor Bjorn Blay of the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH) and Associate Professor Valeria Rueda of the Department of Economics at the University of Nottingham. Vox EU

Deindustrialisation is directly linked to the deterioration of a range of socio-economic indicators. This column examines how the effects of deindustrialisation in the UK reverberate across generations, revealing significant effects on the health, wealth and living standards of people who grew up in a time of deindustrialisation. The ability to migrate to wealthier parts of the country is not enough to offset these negative effects.

Recent declines in industrial employment in developed and emerging economies have been associated with poorer health (Case and Deaton 2020; Case 2020), the breakdown of family ties (Autor et al. 2018), and the shaping of geographies of political discontent (Autor et al. 2020; Rodríguez-Pose 2018; Rodríguez-Pose et al. 2024). Formerly prosperous places are now “left behind,” with declining relative living standards, education, and productivity (Moretti 2022; Overman and Xu 2022). Few countries have seen regional disparities grow more starkly than the United Kingdom, the country undergoing the most rapid deindustrialization in the developed world (Mcann 2019; Stansbury et al. 2023).

In this column, we show that deindustrialization has had a lasting impact on living standards in the UK. Our recent work documents the impact on the health, wealth, and living standards of people who grew up in times of industrial decline. These effects persist even as people migrate from affected areas, and are passed on through generations (Brey and Rueda 2024). Thus, deindustrialization not only affects people working in the endangered industries, but also leaves their children and grandchildren permanently disadvantaged. Moreover, this effect is not fully mitigated even if better economic conditions are available elsewhere. Deindustrialization therefore directly threatens equal opportunity for future generations.

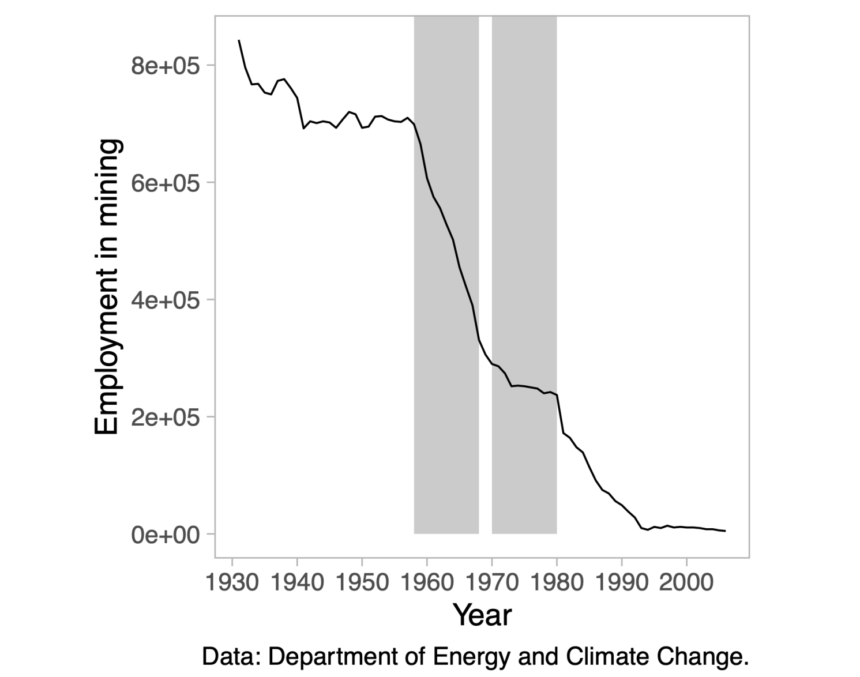

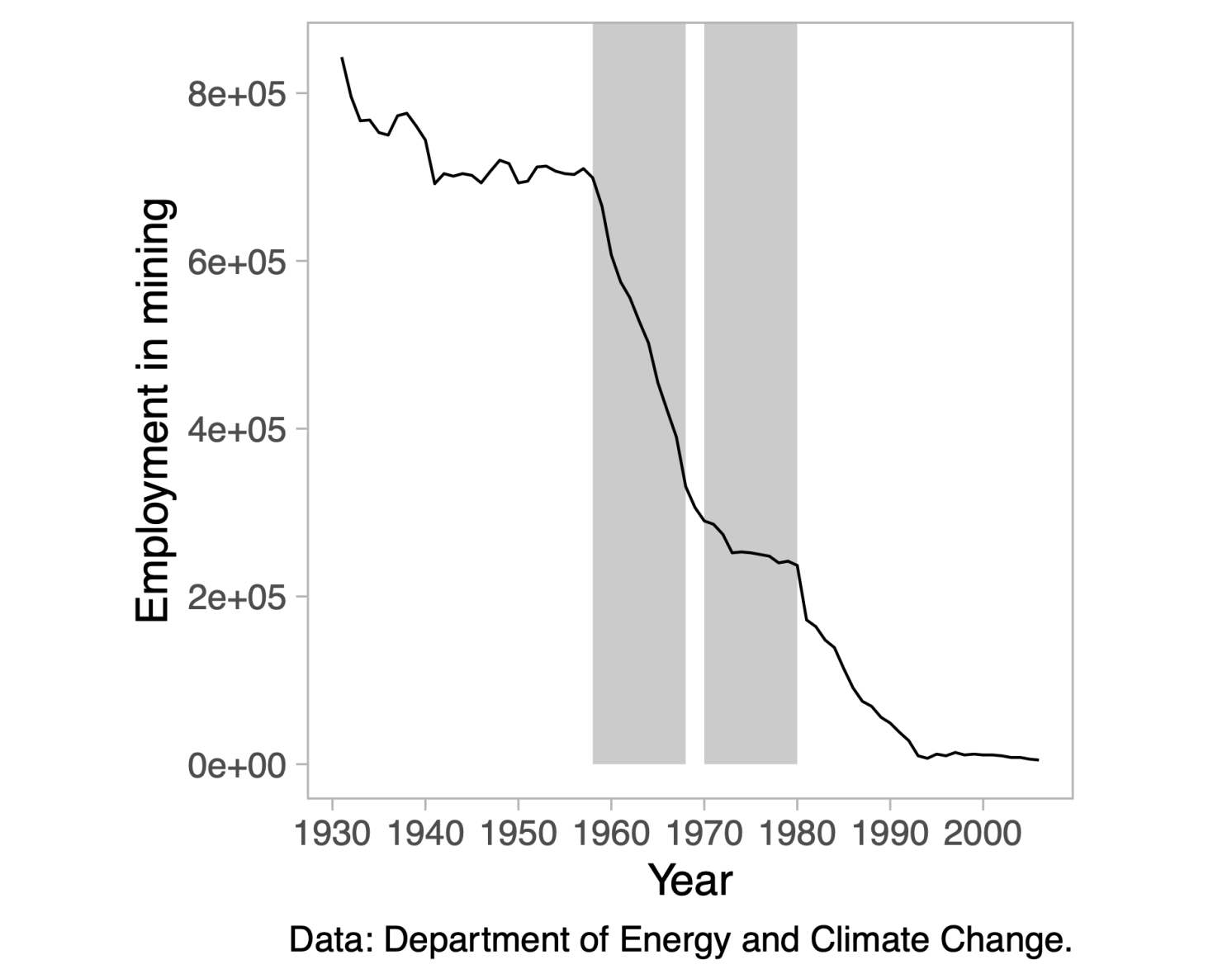

We focus on one of the most striking cases of industrial decline in the twentieth century: the collapse of the British coal industry. Economic historians have written extensively about the importance of British coal in the Industrial Revolution (e.g. Pomeranz 2000; Allen 2009; Wrigley 2010; Fernihough and O’Rourke 2021). By the late 1950s, coal mining employed over 700,000 people. This figure halved within a decade (see Figure 1), following the industry’s biggest contraction since the Second World War. Waves of mine closures continued to hit British coal production, and by the 1990s coal production had virtually disappeared. Now, former coalfield areas are consistently ranked as the most deprived areas in the country, and the issue is well-recognized as a matter of public concern, leading to the formation of a cross-party parliamentary study group (Cross-party Parliamentary Group on Coalfield Areas 2023) to work on policy recommendations for these areas.

Figure 1 Mining employment in Britain in the twentieth century.

NoteSee Brey and Rueda (2024) for further details.

Our paper estimates the impact of coal mine closures on those who experienced this economic shock as children. We exploit longitudinal data (UK Longitudinal Study) that followed all children born in a single week in 1958 and 1970. These data allow us to follow people throughout their lives and collect information on their parents and children. We combine them with data produced and shared by the Northern Coal Mining Research Association, which provides information on all coal mines that operated in the UK. We are thus able to compare outcomes at each life stage, across counties and cohorts, conditional on a rich set of controls, depending on exposure to coal mine closures. We ensure in various ways that our findings are not driven by unobserved confounding factors of coal mine closures and standard of living. In particular, we ensure that children before the shock are comparable. At birth, there is no relationship between health outcomes and socio-economic conditions due to exposure to the shock later. Furthermore, we use fixed effects to account for determinants of standard of living specific to each county and each cohort. Finally, we use instrumental variables that exploit the fact that old mines were the first to close.

Finding 1: People exposed to pit closures during childhood experience poorer health throughout their lives.

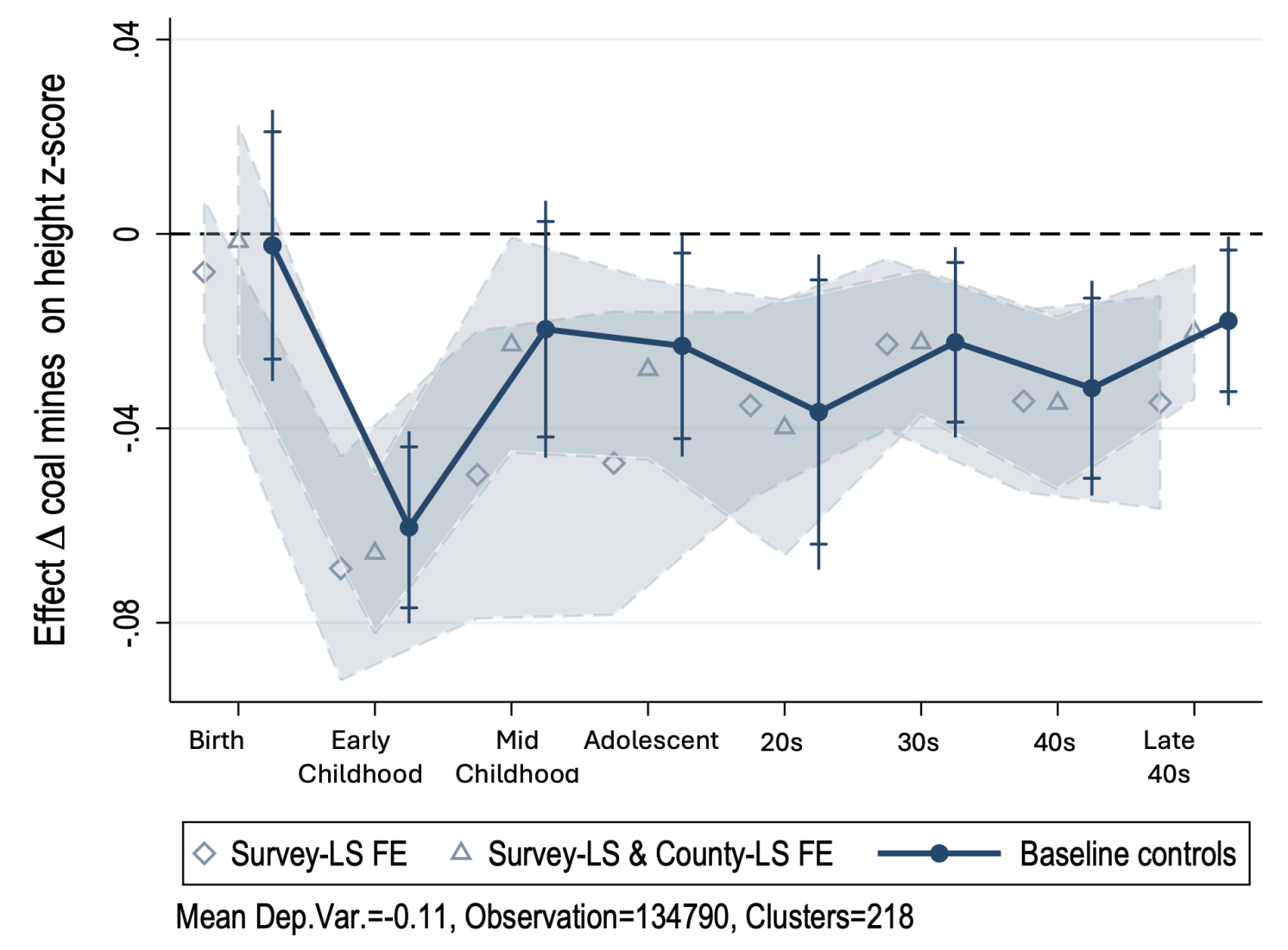

Individuals who grow up in counties with a high percentage of mine closures relative to the population are significantly shorter. Height is a well-established indicator of overall health and living conditions, and is correlated with economic outcomes in adulthood (e.g., Hatton 2014). Height differences are largest in childhood, and although there is some catch-up, significant differences persist into adulthood (see Figure 2). This adulthood difference (4% of the Z-score, or 0.3 cm) is large and comparable to the lower bound estimate of the impact of the Irish Famine on survivor height (Blum et al. 2022).

Figure 2 Impact of mine closure on lifetime height in the population

Note: The coefficients are standardized.

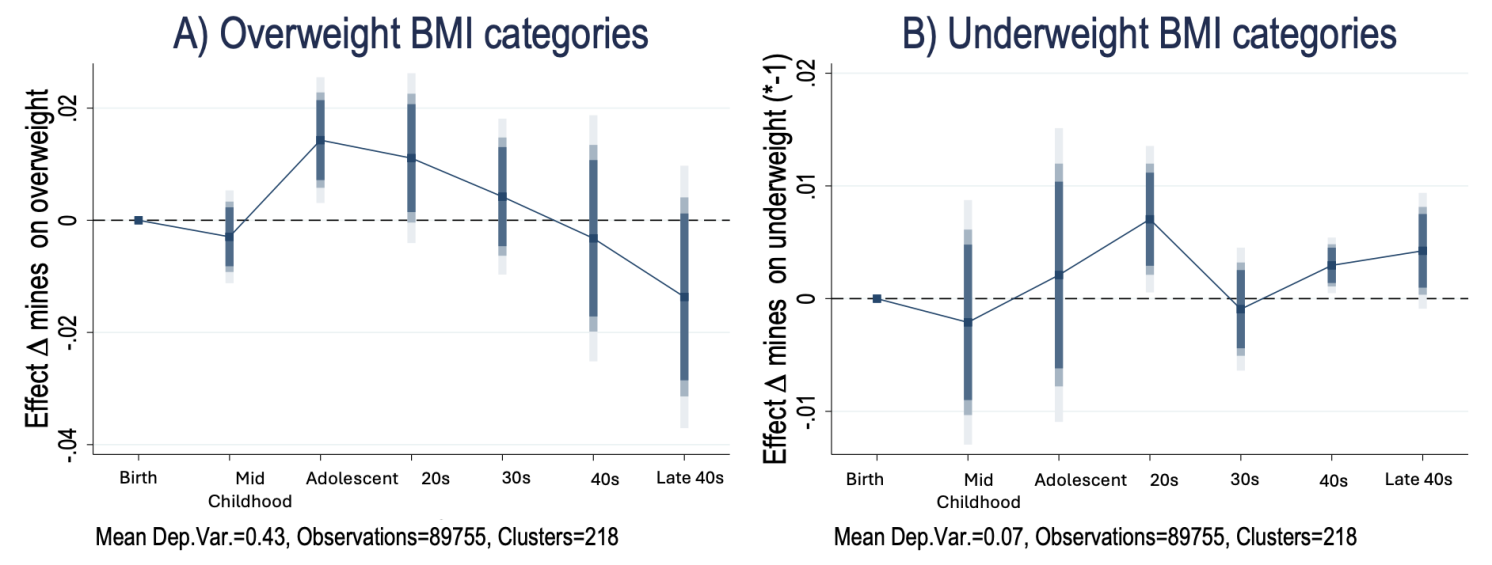

Moreover, the BMI of those who experienced pit closure in childhood is biased towards the extreme categories, with the impact on the overweight category starting from adolescence to the mid-30s, and the impact on the underweight category starting at a later age (see Figure 3).Further analysis shows that the impact on the underweight category is greater in women, while the impact on the overweight category is somewhat more pronounced in men.

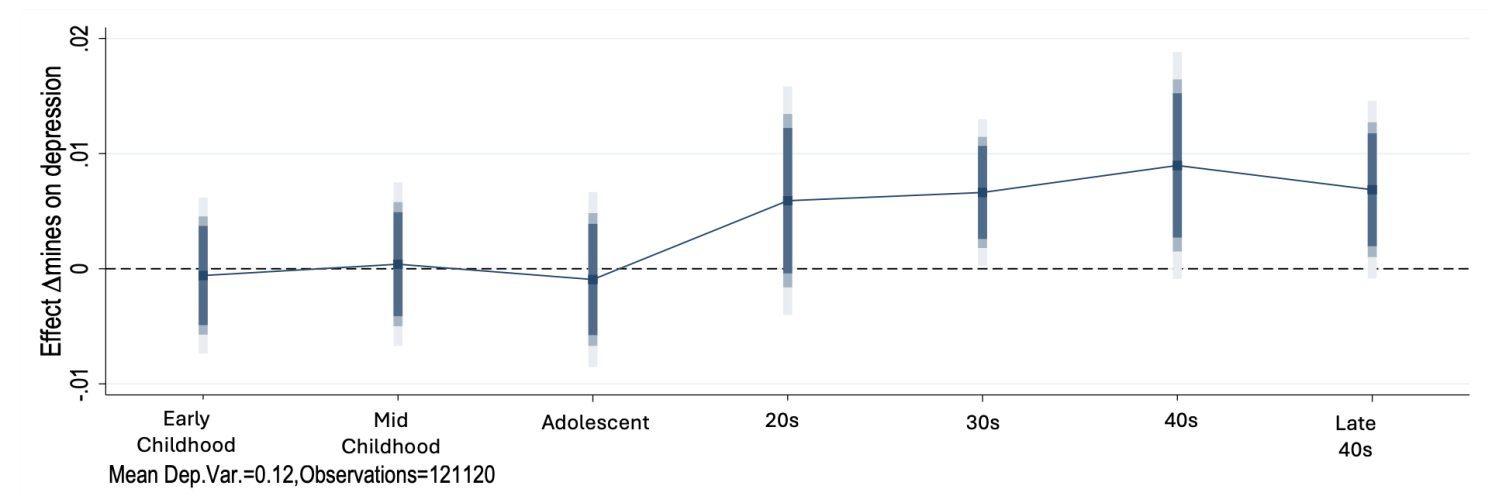

Finally, we also observe worsening indicators of general physical health in childhood and higher incidence of various health conditions in adulthood, such as diabetes, back pain, and cancer. We also observe worsening self-reported mental health in adulthood, with a significantly higher likelihood of being depressed (see Figure 4).

Figure 3 The impact of population exposure to pit closures on extreme BMI categories over the lifetime

Note: The coefficients are standardized.

Figure 4 The impact of population exposure to pit closures on lifetime reports of depressive symptoms

Note: The coefficients are standardized.

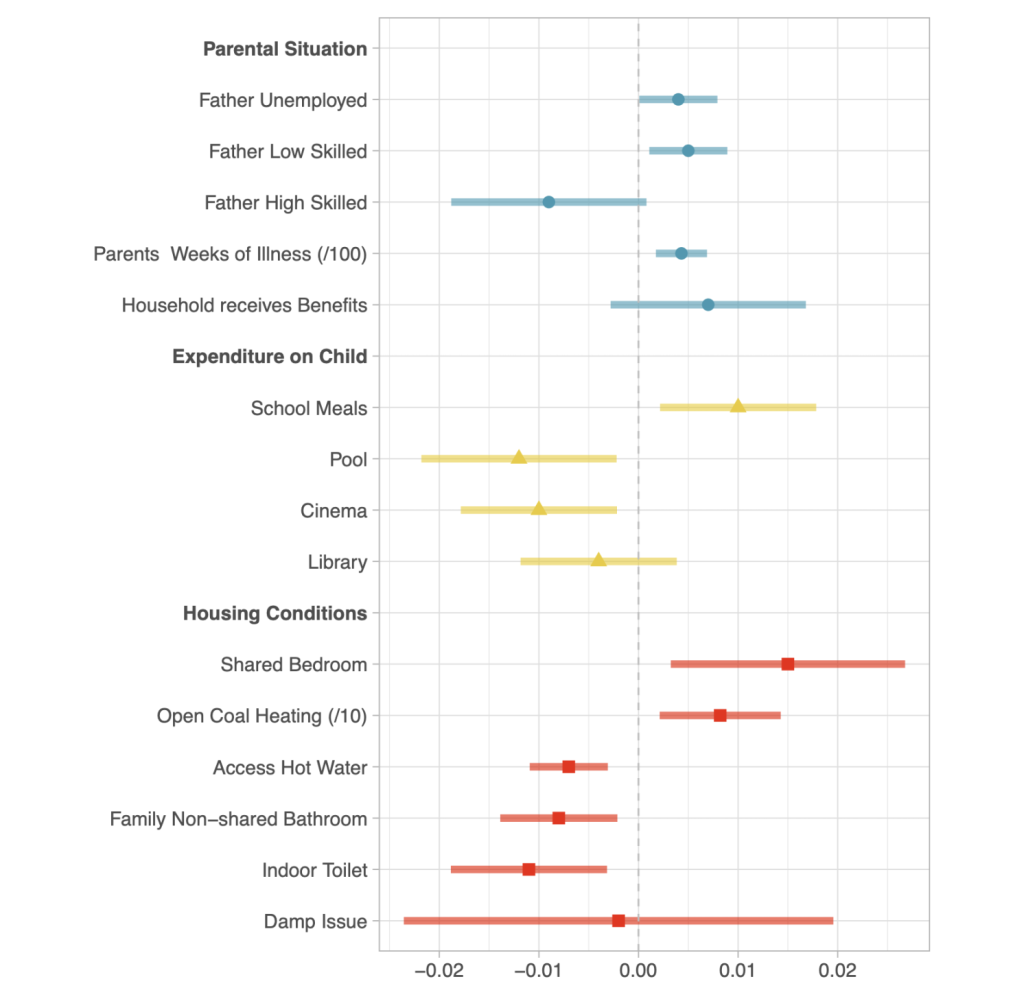

Finding 2: Pit closures are associated with poorer living conditions during childhood

What might explain the lasting effects of mine closures on health? Figure 5 shows that mine closures are correlated with poorer living conditions in mid-life (age 10): parents’ employment status is worse and they are more likely to miss weeks of sickness or receive benefits; children receive fewer resources from their families and are more likely to receive leisure money and free school meals; and finally, children’s housing conditions are worse across a range of indicators. This means that affected children experience economic hardship in their early years, which may contribute to poorer health throughout their lives.

Figure 5 Impact of population exposure to pit closures on children’s living conditions

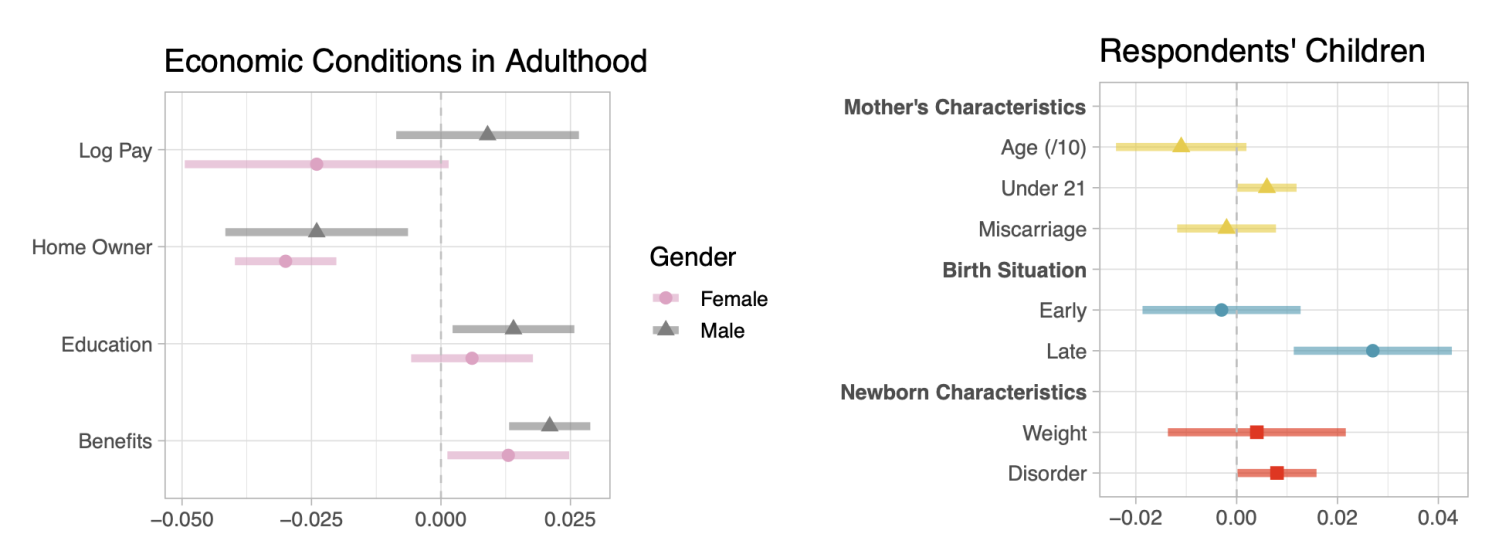

Finding 3: People who experienced pit closures during childhood accumulated less wealth as adults, and their children had poorer health.

How long do these effects last? Do they affect economic situations in adulthood? Are they passed on to the next generation? Figure 6 shows that the economic effects continue into adulthood. Respondents are less likely to own a home, more likely to receive benefits, and women tend to have lower incomes (left panel). Moreover, if they have children, their sons and daughters have a harder start in life: parents have children much earlier (in their teens), babies are more likely to be born later, and they are more likely to have some kind of health condition at birth (right panel, outcome “Disability”).

Interestingly, experiencing a mine closure during childhood is associated with better education, especially for men. This result is consistent with previous findings showing that manufacturing and mining increase the opportunity cost of education, especially for men (Black et al. 2005, Esposito and Abramson 2021, Franck and Galor 2021). Further research is needed to understand why exposure to shocks still shapes wealth despite men’s higher education levels. Potential explanatory channels include health, inheritance, and the direct effects of assortment matching on the marriage market.

Figure 6 The effect of exposure to pit closures on the population of respondents’ adult and children’s economic status

Finding 4: Migration is an imperfect mitigation strategy

In the aftermath of a local economic shock, migrating in search of opportunities is a natural coping strategy. In our case, this was the government’s preferred option and was the reason for rejecting additional targeted support. Longitudinal studies allow migrants to be followed. Three main facts are observed about migration (see section 5.4 in Brey and Rueda 2024). First, the closure of the mine did not induce mobility in later life. Rather, the probability of migration decreases. The incentives to migrate increased, but the resources for it decreased, and this effect seems to dominate. Second, migration is not available to everyone. Those who migrated were born to more educated mothers and fathers or to families with fewer local ties (young parents in single-parent households). Finally, after migration, the impact of the shock is reduced, but not fully reversed. Taken together, our findings suggest that migration was not a perfect solution. Access to migration was unequal and those who migrated still suffer some negative effects.

Lessons Learned

Our research shows that deindustrialization has a lasting impact on living standards, the effects of which can last for generations. These findings are salient in current policy debates (e.g., Institute for Fiscal Studies 2024) about rising inequality and poverty in developed countries. They highlight that without additional support, people born in places left behind by industry will bear health and economic scars that will be passed on to subsequent generations. These long-term effects are not resolved by access to better opportunities; few people migrate, and those who do migrate are left with scars.

look Original Post References