Kevin Corcoran recently did a post discussing the difference between theory being wrong and facts being wrong. What interests me here is another situation where theory matches reality very well, but people are unwilling to accept the implications of the facts. For example, basic economic theory tells us that higher tax rates should lead to fewer hours worked. Europe has higher tax rates than the US, and people work significantly fewer hours each year. But many people seem unwilling to accept the direct implications of these facts.

economist There is a very good article on this topic:

American economist Edward Prescott argued that the key was taxation, reaching a provocative conclusion: Until the early 1970s, tax rates in the US and Europe were similar, as were working hours. By the early 1990s, European taxes had become more burdensome and, in Prescott’s view, employee motivation had decreased. Even today, large disparities remain: US tax revenues are 28% of GDP, compared with around 40% in Europe.

Notice that Prescott relies on two kinds of evidence, cross-sectional and chronological, which make his argument much more persuasive than a simple comparison of two places at a single point in time. Yet many people remain reluctant to accept the obvious implications of these facts.

The article presents one empirical study that suggests the disincentives from high taxes may be rather modest.

Recent research by Josef Sigurdsson of Stockholm University looked at how Icelandic workers responded to a one-year income tax exemption during an overhaul of the tax system in 1987. People with more flexible working arrangements, especially younger people working part-time, did increase their hours, but the overall increase in work was modest compared to what Prescott’s model would suggest.

Again, this result is not at all surprising. Due to the “collective action problem” aspect of the work structure, we expect the short-run elasticity of labor supply to be much lower than the long-run elasticity. Work schedule decisions are generally made at the firm level and to some extent at the societal level (e.g. school schedules that need to be coordinated with work schedules). Note that the elasticity is higher for part-time, younger workers who face fewer coordination problems.

How can we explain this reluctance to accept the obvious implications of the theory? Let me give some further examples to clarify the source of this prejudice.

1. Theory says that rising carbon dioxide concentrations should increase the Earth’s temperature through the “greenhouse effect.”

2. Theory dictates that injecting a large amount of money into an economy should result in price inflation (i.e. a decline in the purchasing power of a dollar bill).

It would be pretty surprising if increasing carbon dioxide didn’t cause global warming, or if spending big money didn’t cause inflation. But I often come across people who disagree with these claims. They might argue that global warming is an unproven theory, or that inflation is caused by corporate greed. Why reject evidence that is almost perfectly consistent with standard theory? What on earth is going on?

I’ve found that people who believe inflation is caused by corporate greed tend to have left-leaning policy views, while global warming skeptics tend to have right-leaning policy views. Perhaps this gives a clue as to why many people are skeptical of the claim that high taxes discourage work.

Let’s say you’re in favor of a large welfare state for various reasons. You might then be reluctant to accept the empirical data showing that high taxes have negative effects. From a purely logical point of view, this doesn’t make much sense. It’s certainly possible that a welfare state is beneficial, even though it leads to a decrease in GDP per capita. Perhaps the increased leisure time is worth the hit to national income.

Unfortunately, when people have strong policy opinions, they tend to behave more like lawyers than scientists: they seek out evidence that supports their policy preferences and they tend to discount evidence that supports their own policy preferences.

Political bias is not the only factor that causes people to reject the implications of economic theory. It is also true that much economic theory is counterintuitive. For example, most elasticities tend to be higher than would be expected if we relied on introspection, or “common sense.” Thus, even people with so-called “addictions,” such as to smoking or illegal drug use, often respond surprisingly well to price signals.

Many people probably find it hard to imagine that higher taxes would lead to people working fewer hours. They might think, “If we raise taxes, then I’ll have to work more hours to pay my bills.” Their mistake is not realizing that tax revenues don’t disappear, but are recirculated in the form of transfers to people who spend more of their leisure time. This is what economists call the “income-adjusted elasticity of labor supply.”

To summarize:

1. If the theory implies that X is true.

2. When empirical evidence tends to support the theory.

Be very careful before rejecting the claim that X is true.

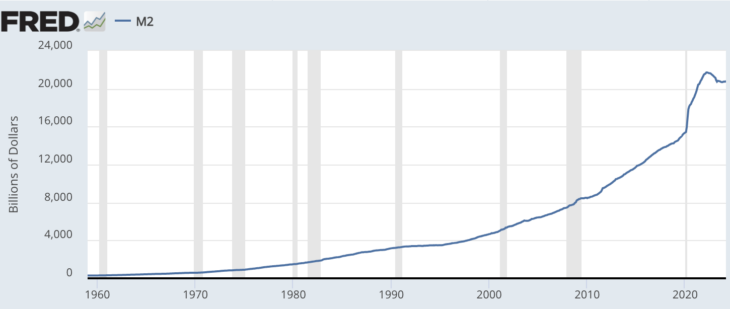

P.S. Imagine if I went back in time and showed David Hume this graph of the M2 money supply:

If you asked Hume what he thought happened to the inflation of the early 2020s, how would he respond? Now suppose we told him that many people blame “corporate greed” for the high inflation of the early 2020s. How would that affect his view of the progress of economics 270 years after he invented the Quantity Theory of Money?