Hi, I’m Eve. As you can see, the debate over releasing nuclear wastewater is about whether proponents know the safety issues properly. The industry claims they do, and that the risks are negligible. Critics argue that it’s a known unknown, there’s not enough time frame, there’s no data to reliably determine synergies with other contaminants, and the released water would not eliminate nuclear contamination.

By Dana Dragmand. New Leads

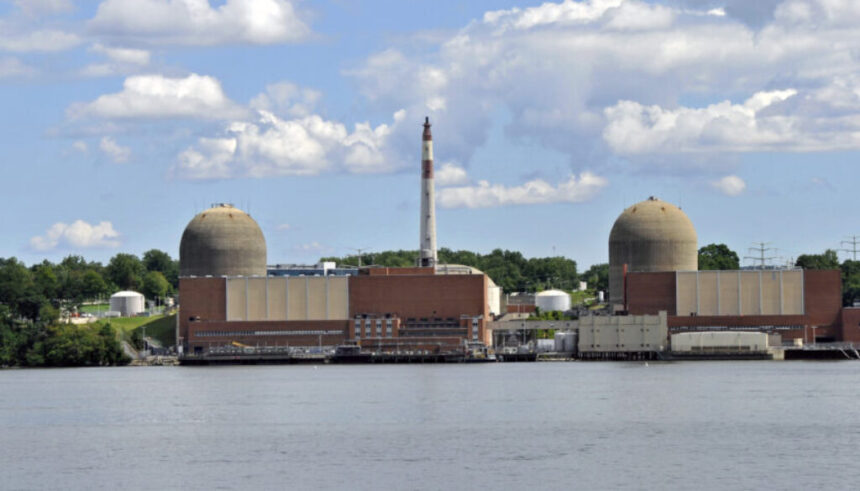

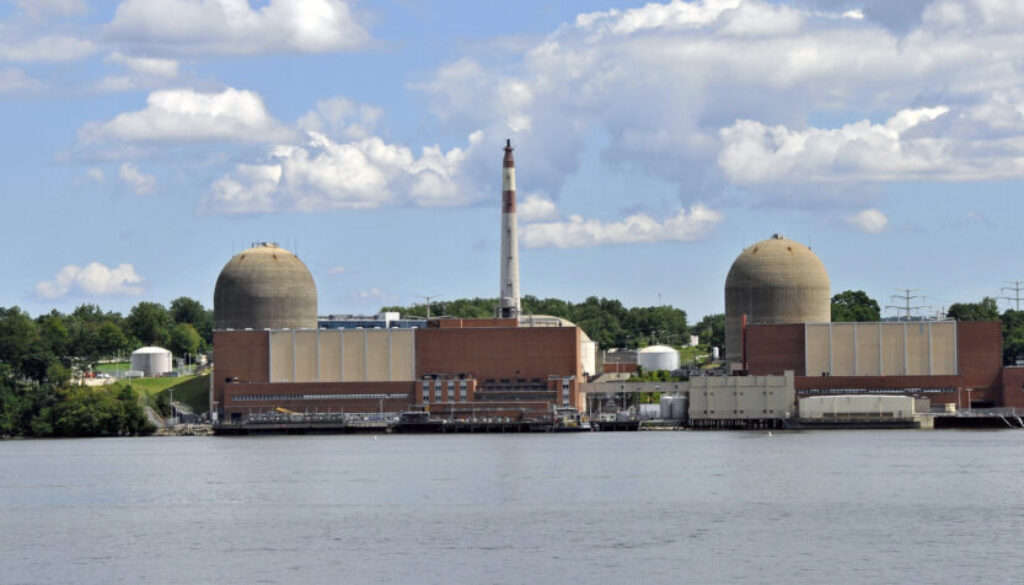

New York state’s efforts to ban radioactive waste from contaminating the Hudson River have embroiled the state in a bitter legal battle that symbolizes the challenges facing communities across the country struggling to dispose of waste from shuttered nuclear plants.

At the heart of New York’s problem is the law Established in August last year The lawsuit seeks to block Holtec International’s plan to dump more than one million gallons of radioactive wastewater into the river during the decommissioning of the Indian Point Nuclear Power Plant. Sued the state It argued in April that the emissions were permitted under federal regulations that supersede state regulations.

The state counterclaimasking the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York to dismiss Holtec’s claims and approve the state’s new ruling.

The United States has long had the world’s largest fleet of nuclear power plants, and from the late 1980s to 2020, nuclear power accounted for about 20% of annual electricity generation. according to There are currently more than 90 commercial nuclear reactors operating at 54 nuclear plants in 28 states, according to the Congressional Research Service, but many have closed over the past decade and more are scheduled to close due to financial challenges and disputes with environmental and public health advocates. Some risks Related to the facility.

The battlefield extends far beyond New York, and Holtec faces similar communities. Opposition to the plan Discharging radioactive wastewater from the decommissioning of the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plantt For example, from eastern Massachusetts to Cape Cod Bay.

“Clearly, no one wants to dump nuclear waste into the water,” said Santosh Nandavaran, an activist with Food & Water Watch, which campaigns against the dumping of nuclear waste. “Now that it’s in law, I think Holtec needs to follow through. We’re going to continue to rally support and hold Holtec accountable so the Hudson River doesn’t become a dumping ground.”

Holtec spokesman Patrick O’Brien told the New Lead that Holtec’s goal is to “safely decommission these plants and Returning assets as economic drivers for local communities He said the company has been “open and forthright and has answered questions as they have arisen.”

O’Brien said opponents of releasing the radioactive wastewater were “trying to peddle fear rather than fact,” adding that “the reality is you’d get more radiation from eating a banana or a Brazil nut than you would from releasing it.”

General Practice

Proponents of nuclear wastewater discharges argue that there is little risk because contaminants are diluted in receiving waters. They point out that environmental discharges of radioactive materials are routine in the nuclear industry and Safely Manage.

Radioactive spent fuel from nuclear power plants is typically stored on-site in liquid pools or dry storage vessels, and this waste is accumulate by Approximately 2,000 tons per year No permanent repository has been established to bury the waste.

Water used for cooling and storing spent fuel is also radioactive and needs to be managed and disposed of, and it is common for treated wastewater to be discharged into local waterways both during operation and decommissioning of nuclear power plants.

of Retirement Plan For example, the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant in California will discharge treated wastewater into the ocean, while other radioactive waste will be stored on-site or shipped off-site.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) Website The federal agency “regulates the disposal of radioactive waste,” which “includes transferring the material or waste to an authorized recipient, storing it for decay (disintegration in storage), and safely discharging it to the environment (discharge release).” Any disposal method that meets applicable NRC regulations may be selected. While the latter disposal method may technically be considered “safe” according to regulators, it has raised alarm in some communities, particularly in areas surrounding nuclear power plants undergoing decommissioning and in nearby waterways that receive radioactive releases.

However, opponents of releasing waste into the environment argue that regulators have not considered long-term, intergenerational toxic exposure to these substances or their interactions with other environmental contaminants to which the public is exposed.

“We need a complete, intergenerational restructuring of how we think about these radioactive releases,” said Cindy Folkers, an expert on radiation and health hazards. Beyond the core“Radiation doesn’t exist in a vacuum. That’s part of the problem. Nobody’s looking at the synergistic effects.”

Ernie GundersenThe Fairwinds Energy chief engineer and nuclear industry decommissioning expert also said federal regulators don’t consider the full extent of environmental contamination when allowing nuclear facilities to release radioactive material.

Wastewater from nuclear power plants contains tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, which is harmful and potentially carcinogenic. Dumping large amounts of this radioactive wastewater into waterways that are already contaminated with toxins like PFAS and PCBs could create an even bigger pollution problem, he said. For example, he noted, the Hudson River is known to be contaminated with PCBs.

“There’s this thing called synergistic toxicity,” Gundersen says. “The NRC regulations don’t take that into account, and the EPA regulations don’t take that into account.” The science of how tritium interacts with or affects other chemical contaminants isn’t fully understood, which calls for a precautionary approach to the disposal of radioactive wastewater from nuclear power plants. “There’s definitely insufficient science to allow disposal.”

Searching for alternatives

The Indian Point Nuclear Power Plant in New York state, located on the east bank of the Hudson River about 25 miles north of New York City, permanently shut down operations in 2021. Holtec, a private equity firm and leader in the fast-growing nuclear decommissioning business, acquired the plant with plans for accelerated decommissioning, including the release of 1.3 million gallons of radioactive wastewater into the Hudson River.

However, when environmental activists learned of the plan, they quickly launched a campaign against it and pressured the state to pass a law they called “Save the Hudson.”

In Massachusetts, Holtec is facing similar backlash over the closure of its Pilgrim nuclear plant in Cape Cod Bay. The company currently does not have the legal authority to discharge into the bay and is reportedly considering evaporating its wastewater.

April 30, 2024 letter “There is no doubt that evaporating wastewater from Pilgrim poses potential risks to health and the environment,” said a letter sent by Senators Ed Markey and Elizabeth Warren and Representative William Keating to Holtec’s president and CEO. The letter asked the company to: Listening to local concerns Regarding releasing waste into the air and water.

The nuclear waste disposal dilemma is not unique to the US: In Japan, the Fukushima nuclear plant is releasing treated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean. Starting in March 2024However, the option of releasing the radioactive water into the ocean is highly controversial, and the move has led China to ban seafood imports from Japan.

According to an expert who studies the environmental impacts of radioactive contaminants in the environment, wastewater releases from Fukushima are not expected to have a significant impact on marine ecosystems.

Jim SmithProfessor of Environmental Science at the University of Portsmouth in the UK, paper “It is common practice for nuclear facilities around the world to discharge wastewater containing (tritium) into the sea,” the report, published in October, noted. Releasing large amounts of water that contain small amounts of the radioactive nuclide tritium is generally safe, Smith told the New Lead. “The radiation dose to the public from such a release would be extremely small and negligible,” he said.

Despite these reassurances, he said it was “completely understandable” that people would be worried about the possibility of radioactive water being released into their local environment. Allison McFarlane“It’s really important that nuclear companies and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission work with the public that will be affected,” said Professor and Dean of the School of Public Policy and International Affairs at the University of British Columbia, and former NRC chairman.

One disposal method would be to package the wastewater and ship it to a licensed treatment facility, as another nuclear decommissioning company, NorthStar, has done. Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant.

Another option for contaminated wastewater is long-term storage before release. Storing contaminated wastewater for 10 to 20 years to reduce its radioactivity is an alternative to a rush-to-dispose approach, and it’s probably best suited for the more than 1 million gallons of radioactive water at the Indian Point, New York, plant, Gundersen said. “We recommend storing it until we know the science behind releasing tritium into water that’s already contaminated with PCBs,” he said.

As for the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant in Massachusetts, which Holtec acquired in 2019, the company Evaluated alternative wastewater treatment options They concluded that discharging into Cape Cod Bay would be the most convenient and least expensive disposal method.

Holtec denies the option of long-term on-site storage; evaluation “The impact on the decommissioning schedule is a factor in the evaluation of alternatives,” the company said. Discharging treated wastewater into the bay would be “most protective of human health and the environment” because remaining contaminants and radionuclides such as tritium would be diluted to the point where they are barely detectable, the company said.

But Forkers said this argument is misleading. “If something is dilute, the assumption is that it’s going to stay that way, but radioactivity moving through the environment doesn’t stay that way.” She said there’s “a lot of confusion swirling” about tritium, which is routinely released into the environment by nuclear power plants. It’s released in very low doses that have long been thought to be relatively harmless. Emerging Science Suggest This radioactive material perhaps More dangerous than previously thoughtParticular care should be taken with pregnant women and children.

“Those who support environmental releases (of tritium) believe it’s safe because it has low beta energy, but radioactivity is not,” said Voelkers. “What we need to look at is the long-term releases — releases that have occurred over 40 years — and the environmental and health and biological effects of that contamination for generations to come.”

NRC It says on the website “Any exposure to radiation may pose some health risks, including an increased risk of cancer,” it warns. The agency sets dose limits “well below the levels of radiation exposure that would cause health effects in humans, including a developing fetus. The effects of high doses and high dose rates are well understood. However, public health studies have not demonstrated health risks at low doses and dose rates.”

For Forkers, our limited understanding of the public health effects of long-term exposure to low-level radiation gives us even more reason to question the assumption that releasing radioactive waste is safe.

“It’s becoming increasingly clear that we’re not looking at radiation exposure in the way that we need to,” she said.

(Featured photo By Tony Fisher.)