gyro

Yusuke Hashimoto

Passive quantitative tightening could be the Bank of Japan’s next step towards normalization, for several reasons:

In March, the Bank of Japan ended its eight-year negative interest rate policy and raised interest rates for the first time in 17 years. Lowering the base interest rate to between 0 and 0.1 percent. This move is long overdue, but it is just one step on the road to normalization.

We believe the BOJ should take its time along the way. In our view, policy normalization is best done slowly. The resulting lower volatility, higher yields and a steeper yield curve will be a favorable environment for fixed income investors. But what exactly would be the ideal next step for the BOJ on its normalization path?

Interest payments could curb further rate hikes

One of the next steps the BOJ could take is to raise interest rates again. Exorbitant increase in interest payments.

How much of an increase is excessive can be determined by calculating the breakeven interest rate on cash flows, i.e. the maximum interest rate at which interest income from the Bank of Japan’s excess reserves is sufficient to cover interest costs on the debt.

Given the excess reserve balance of 548 trillion yen, a 10 basis point (bps) interest rate, the latest upper limit of the rate hike, would result in interest payments of 548 billion yen. Potential break-even rates are 60bp based on FY2022 recurring profits and 80bp based on FY2023 recurring profits. Interest payments at these levels would be 3.3 trillion to 4.4 trillion yen, respectively. Beyond this level, further rate hikes could be possible if the BOJ uses its reserve balance. Unrealized Bond Trading Losses.

But we believe there is a different, better option for the next step back to normalcy.

First: Passive quantitative tightening

To combat inflation and avoid an excessive surge in interest payments, the Bank of Japan is considering passive quantitative tightening (QT). Under this approach, the central bank would shrink its balance sheet by simply redeeming its holdings of Japanese government bonds (JGBs) and restricting their redemptions. By strategically shrinking its balance sheet first, the Bank of Japan would reduce the size of future interest payments, reserving the option to raise interest rates by 50 basis points once the balance sheet shrinks and the cost of interest payments falls.

Another advantage of this approach is that it buys the central bank time to assess the impact of an initial rate hike on the Japanese economy. Japan’s natural interest rate, or r*, which defines the economy’s real potential growth rate, has likely risen, but by how much? The answer will help the BOJ refine its policy stance.

Unfortunately, estimating R-Star in real time is difficult anywhere, but especially in Japan, where short-term interest rates have been hovering near zero for three decades and the yen has weakened against other currencies. In these circumstances, time to assess the situation is especially valuable.

Taking a phased and passive approach to QT has other benefits. First, the BoJ avoids the potential financial market turmoil that comes with asset sales, which means market volatility can remain low. Meanwhile, by reducing demand for bonds and sending a signal of less accommodative policy, the BoJ can effectively induce higher long-term interest rates, steepening the yield curve.

Reviewing the final results: potential QT targets

For these reasons, the Bank of Japan is expected to gradually reduce its bond purchases, depending on the market’s reaction. Japan’s Ministry of Finance has indicated that it has room to reduce its balance sheet by about 160 trillion yen. But at what pace?

Currently, the Bank of Japan purchases about 6 trillion yen worth of government bonds each month to cover redemptions. If the Bank of Japan were to reduce this to about 3 trillion yen per month, it would reduce its balance sheet by 36 trillion yen per year. At this rate, it would take more than four years to reach the total reduction target of 160 trillion yen.

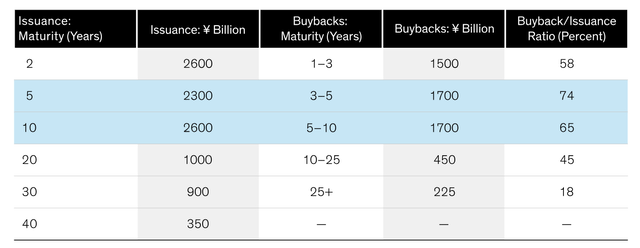

In our view, the BOJ is likely to focus its share buyback reductions on the 3-5 year and 5-10 year regions of Japan’s yield curve, as these maturities currently have the highest share buyback and issuance ratios among government bonds (screen) so there is some room to cut.

5-year and 10-year bonds are most likely targets for the BOJ’s share buyback cuts

Japanese government bond issuance and repurchase: monthly average

Current analysis is not a guarantee of future results. Issuance amounts are for fiscal year 2024 (April 2024 to March 2025), and repurchase amounts are based on purchases in the Bank of Japan’s most recent auction. As of May 31, 2024 (Source: Bank of Japan, Ministry of Finance, AllianceBernstein (AB))

If the BOJ were to reduce its buybacks of these maturities, the yields on these bonds would rise relative to yields on other maturities, and the resulting decline in demand would likely cause that part of the yield curve to steepen.

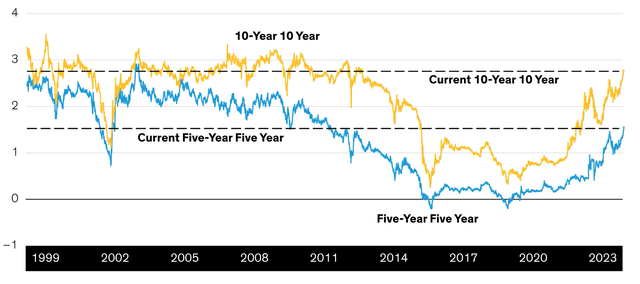

Focusing cuts in these areas could help correct a recent distortion in which 10-year forward yields, the projected yield on 10-year bonds issued 10 years from now, have returned to pre-aggressive quantitative easing levels while 5-year forward yields have not.screenIn theory, the 5-year futures 5-year Treasury yield should be equal to the current 10-year Treasury yield.

The forward yield curve is skewed

5-Year Futures 5-Year Futures and 10-Year Futures 10-Year Futures Treasury Yield (Percent)

Past and present analysis is no guarantee of future results. Through May 30, 2024 (Source: Bloomberg)

Slow but steady is the path to victory

To us, a gradual and passive QT would be an ideal next step for the BoJ. The resulting lower volatility, higher yields, and steeper yield curve would be good news for both the central bank and bond investors. That’s why we think a slow and steady approach to normalization makes sense.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trading recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of the AB portfolio management team as a whole. Views may change over time.

Editor’s note: The summary bullet points for this article were selected by Seeking Alpha editors.