Eve is here. In his following case study of post-election currency devaluation, serious economist Jeffrey Frankel makes it clear that he limits himself to Third World examples. Perhaps it would be unseemly to look at the US, UK, Japan, South Korea, or even Australia (certainly the latter and Canada, whose currency values are heavily influenced by commodity prices). Of course, Mr. Frankel might argue that any politically related currency actions in advanced economies do not result in lower levels of currency depreciation. After all, they have an independent central bank.

As many people have pointed out, including your humble blogger, the United States has implemented very tight fiscal policy alongside tight monetary policy. Therefore, the US continued to have strong to very strong numbers, prompting the Fed to continue tight monetary policy. All of this has led to the dollar trading at extremely high levels.

You have to think that the dollar will start to reverse closer to the election, say in October. But inflation is very sticky, and interest rates are what’s pushing the dollar higher, so it could remain relatively strong after the election. Furthermore, the United States has had a clear policy of strengthening the dollar since at least the Clinton administration. Weak currencies and financial centers do not coexist happily. Until now, the Federal Reserve has paid no attention to how changes in interest rates in emerging countries, which are routinely influenced by movements of hot money, have affected capital flows into and out of emerging countries. One wonders if the Fed will eventually start paying more attention to the value of the dollar.

Currency-savvy readers are encouraged to weigh in on which countries look more attractive as the King Dollar retreats from its current highs.

Written by Jeffrey Frankel, economist and professor at Harvard Kennedy School. It was first published in Vox EU

In 2024, an unprecedented number of voters will go to the polls around the world. It has long been noted that incumbents tend to engage in expansionary fiscal (and where possible monetary) policies in the run-up to elections in order to stimulate the economy and, by extension, elections. Outlook. In this column, we extend this concept to exchange rates and analyze incumbents’ efforts to overvalue their currencies in the run-up to elections, as the new government comes to terms with depleted foreign exchange reserves and current account woes. Because of this, they found that currencies often depreciate after elections. .

Many countries are voting and 2024 will be an unprecedented year in terms of the number of people going to the polls. Recent elections in many emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have reaffirmed the proposition that devaluations of major currencies are more likely to occur immediately after elections rather than before. In fact, five countries have experienced post-election currency devaluations within the past year: Nigeria, Turkey, Argentina, Egypt, and Indonesia.

Cycle of elections and devaluation

Economists will remember Nobel Prize winner Professor Bill Nordhaus’s 50-year-old paper as essentially the beginning of the study of political business cycles (PBCs). The PBC notes the general tendency of governments toward fiscal and monetary expansion in the year leading up to elections in hopes of reelecting the incumbent president, or at least the incumbent party. The idea is that output and employment growth will accelerate before the election, making the government more popular, but that the high costs of debt problems and inflation will come after the election.

However, the seminal 1975 paper by Nordhaus also included predictions of currency cycles specifically related to EMDE. The proposition is that countries generally try to shore up the value of their currencies before elections, draw down foreign exchange reserves as necessary, and devalue their currencies only after elections.

Nordhaus writes:Concerns about loss of foreign exchange reserves and balance of payments deficits are predicted to be greater at the beginning of the electoral system and diminish towards the end. …A fundamental difficulty in making intertemporal choices in democratic systems is the implicit weighting function for consumption. positive weight during the election period and zero (or small) weight in the future”

This devaluation may have been done deliberately, with the incoming government choosing to avoid the unpopular and unpleasant step of worsening inflation while it could blame its predecessor. Alternatively, currency devaluation could take the form of an overwhelming balance of payments crisis immediately after the election. In any case, governments have an incentive to hoard foreign exchange reserves early in their term and spend them more freely towards the end of their term to protect their currency.

Political leaders, especially in presidential democracies, are almost twice as likely to lose their jobs within six months after a deep devaluation than they would otherwise be (Frankel 2005). Why are currency devaluations so unpopular that governments fear devaluations before elections? In the traditional textbook model, currency devaluations stimulate the economy by improving the trade balance. But currency devaluation always causes inflation in countries that import at least part of the basket of goods they consume. Furthermore, EMDE devaluations often reduce economic activity through negative balance sheet effects, particularly for domestic borrowers with dollar-denominated debt.

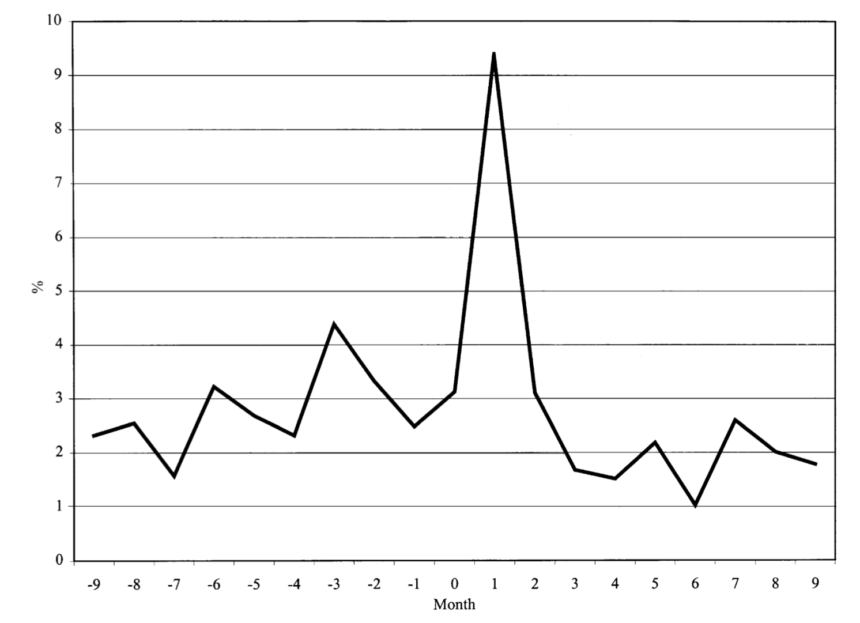

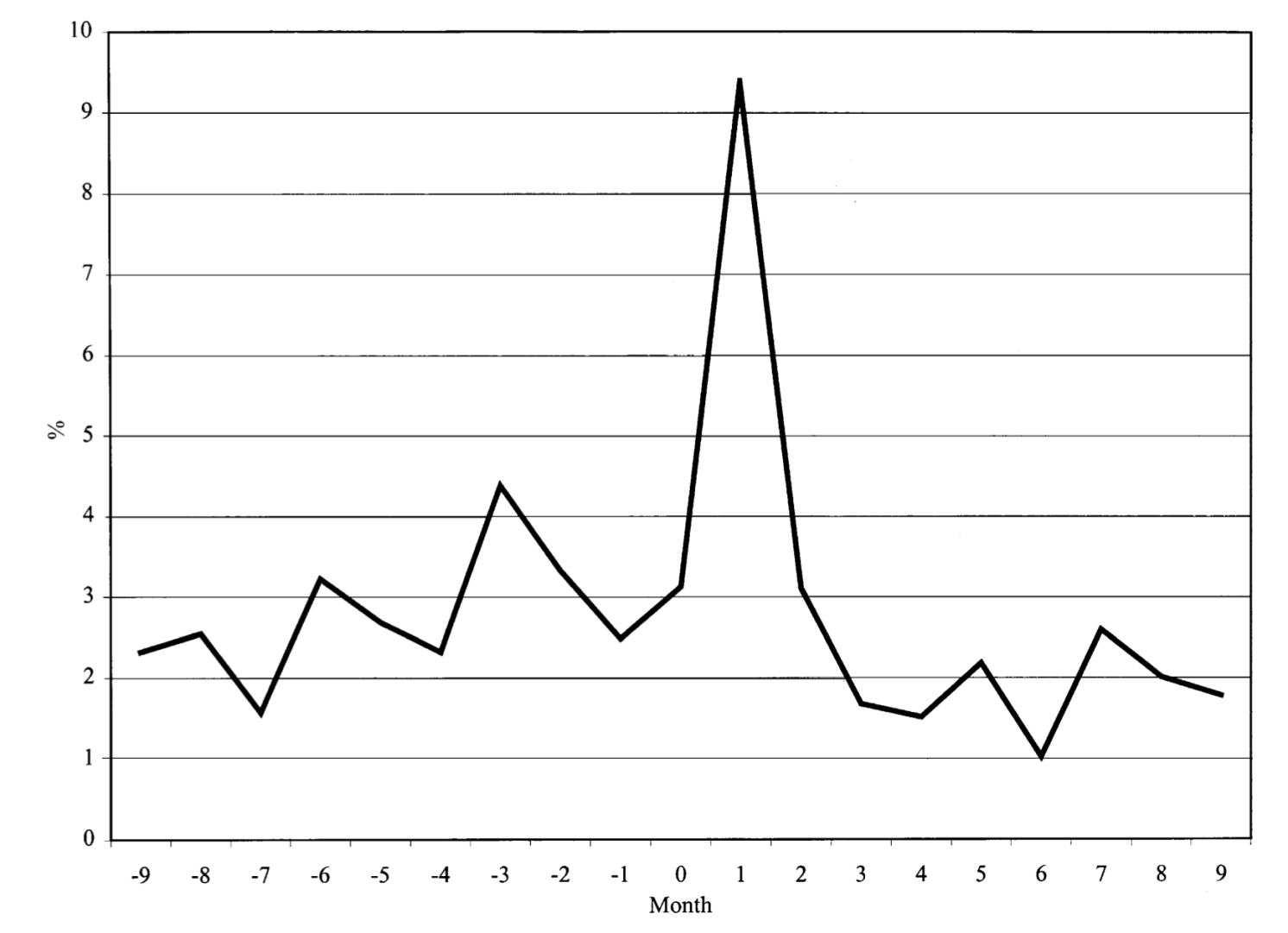

The theory of political devaluation cycles was developed in a series of papers by Ernest Stein and his co-authors. One might think that voters would be wise to these cycles and vote against leaders who quietly postpone necessary exchange rate adjustments. However, given the lack of information about the nature of politicians, voters may actually be acting rationally. Figure 1 of Stein and Streb (2005) shows that devaluations are much more common immediately after a government change. (This sample covers 118 episodes of change, excluding coups, in his 26 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean from 1960 to 1994.) 1

Figure 1 Average devaluation pattern before and after elections

sauce: Stein and Streb (2004).

Some ratings have been devalued in the past year

Many EMDEs have been under balance of payments pressures over the past two years. One factor is that the U.S. Federal Reserve significantly raised interest rates in 2022-2023 and is now keeping them at higher levels for longer than the market expected. As a result, foreign investors find US Treasury bills more attractive than EMDE loans and securities.

A good example of a cycle of political devaluation is Nigeria. Africa’s most populous country held a controversial presidential election on February 25, 2023. The term-limited incumbent has long used currency intervention, capital controls and multiple exchange rates to avoid devaluing the naira currency. Nigeria’s new president, Bola Tinab, took office on May 29, 2023. Two weeks later, on June 14, the government devalued the naira by 49% (logarithmically calculated from 465 Naira/$ to 760 Naira/$). It soon became clear that this was not enough to restore equilibrium to the balance of payments. At the end of January 2024, the government abandoned efforts to increase the official value of the naira and further devalued it by 45% (logarithmically from 900 Naira/$ to 1,418 Naira/$).

The second example is the Turkish elections in May 2023. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has long pursued economic growth by requiring the central bank to keep interest rates low, although his populist monetary policy was widely derided as the president insisted it would curb soaring inflation. , while simultaneously intervening to support the value of the lira. The government guaranteed the depreciation of Turkish bank deposits, but this was an expensive and unsustainable method of prolonging the currency’s overvaluation. As the theory predicts, after the election, the lira was immediately devalued. The currency continued to decline throughout the year.

Then, on November 19, 2023, Argentina elected Javier Millei as a surprise candidate for president. well explained He is a far-right liberal and is not from an established political party. He campaigned on a platform of drastically reducing the government’s role in the economy and eliminating central banks’ ability to print money. Mr. Millay took office on December 10th. Two days later, on December 12, he cut the official price of the peso by more than half (from 367 pesos/dollar to 800 pesos/dollar, a logarithmic devaluation of 78%). At the same time, he put a chainsaw into government spending, including energy subsidies, rapidly running into budget surpluses and embarking on sweeping reforms. Argentina’s inflation rate remains very high, but again as predicted by theory, the central bank stopped the decline in foreign exchange reserves after devaluing the currency.

The fourth example is Egypt, where President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi just started his third term on April 2, 2024. The economy has been in crisis for some time. Nevertheless, the government secured a resounding re-election on December 10-12, 2023 by postponing unpleasant economic measures, not to mention blocking serious opposition candidates. The widely anticipated devaluation of the Egyptian pound resulted in a 45% depreciation on March 6, 2024 (logarithmically, from 31 Egyptian pounds/$ to 49 Egyptian pounds/$).it was part of extended access IMF programwhich also included the always unpopular monetary and fiscal discipline.

Finally, in Indonesia, the widely popular but term-limited President Jokowi will soon be succeeded by Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto. Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto is less popular, but was endorsed by the incumbent in the February 14 election. The rupiah has been depreciating since the results of the controversial presidential vote were announced on March 20. On April 16th, the currency fell to almost an all-time low against the dollar.

What’s next?

Of course, the link between elections and exchange rates is unavoidable. Elections are currently being held in India, and elections in Mexico will be held in June. However, neither appears to require particularly large currency adjustments.

Venezuela is scheduled to hold presidential elections in July. As in some other countries, the election is expected to be a sham as major opposition candidates are not allowed to run. The economy is in chaos due to years of mismanagement, including recent hyperinflation and chronic overvaluation of the bolivar. But the same government that makes political opposition essentially illegal also makes buying foreign currency essentially illegal. Therefore, equilibrium in the foreign exchange market may not be restored for some time.

To prevent currency devaluation, these countries do more than just spend their foreign exchange reserves. They often use capital controls and multiple exchange rates rather than allowing free financial markets. However, this does not invalidate the phenomenon of post-election currency devaluation. It only serves to distance governments a little further from the need to adapt to the realities of macroeconomic fundamentals. Unfortunately, many of these countries do not allow free and fair elections, which also avoids the need for governments to respond to the verdict of voters.

Author’s note: A shortened version of this column is project syndicate. He would like to thank Sohaib Nasim for research assistance.

look original post for reference