Hi, Yves. This article contains a careful and credible analysis of how significant deviations from normal temperature levels (here in the hot direction of Mexico) increase default levels and subsequently restrict lending for a period of time. The impacts are disaggregated at the municipal level rather than the whole country. The author makes some suggestions, mainly on the credit/financial side, but there is not much that can be done to improve crop yields and reduced worker productivity.

Sandra Aguilar Gómez, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Los Andes; Vox EU

A recent report from the International Panel on Climate Change noted a steady increase in extremely hot days, affecting agriculture and other sectors. Economic impacts include lower labor productivity and increased operating costs. Recent studies have also highlighted the impacts of climate on the financial sector, especially in low- and middle-income countries. This column delves into financial vulnerabilities in Mexico, finding a link between extreme heat and rising delinquency rates, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises. Policies need to address these risks and link climate resilience with strengthened access to credit for vulnerable businesses.

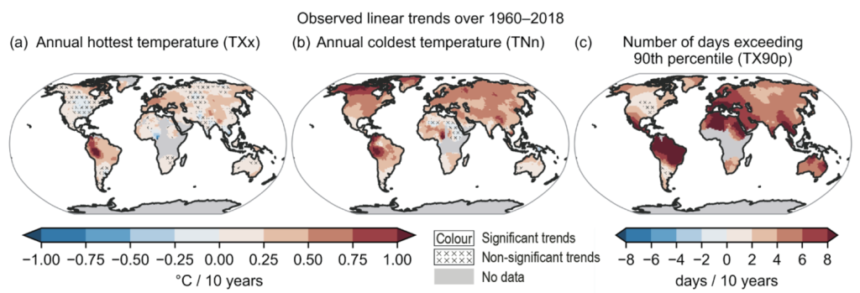

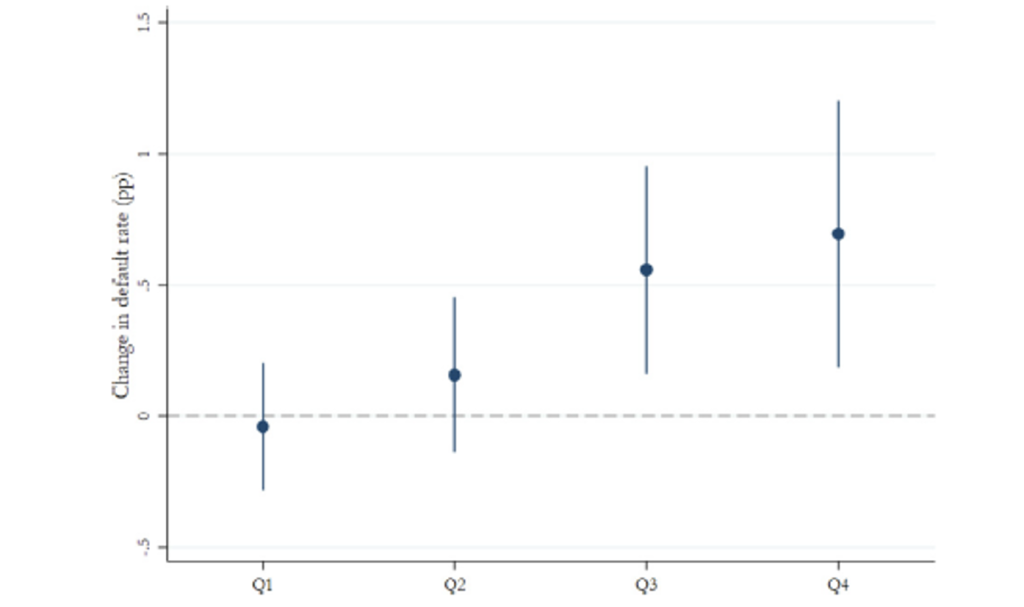

Climate change is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. Heatwaves are of increasing concern, breaking temperature records every year (IPCC 2021). Figure 1 shows an analysis of the latest assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6). Over the past half century, the number of days above the 90th percentile of regional distribution has steadily increased. In agriculture, it is not surprising that studies have found that crop yields are adversely affected by deviations from optimal conditions for plant growth. However, the economic impacts of warming go beyond the agricultural sector. Higher temperatures make work more uncomfortable and some goods and services more attractive than others. Higher temperatures also make people more aggressive and make poorer decisions. Economists have found that these effects translate to business gains through lower labor productivity, increased worker absenteeism, and changes in local demand. When companies spend resources to mitigate some of these effects (for example, by increasing air conditioning use and shortening shifts for tired workers), they also increase their operating costs. In a recent Vox column, Ponticelli et al. (2023) discuss empirical findings that as temperatures rise in the United States, factory productivity falls, leading to the closure of small factories and increased manufacturing concentration in the medium term.

Figure 1 Linear trends from 1960 to 2018 for three extreme temperature indices: annual maximum daily maximum temperature (panel a), annual minimum daily minimum temperature (panel b), and annual number of days with daily maximum temperature above the 90th percentile from the base period of 1961 to 1990 (panel c).

sauce: IPCC (2021) Figure 11.9.

Central banks and other financial institutions are increasingly concerned about the impact of such shocks on the financial sector (Reinders et al. 2023). The impact of adverse weather on costs and demand can create liquidity shortages for firms, leading to solvency problems. There are several circumstances that suggest that firms may be more vulnerable in developing countries. For example, suppose that defaults caused by shocks increase lenders’ uncertainty about borrowers’ future ability to repay loans. In that case, lenders may increase interest rates on new loans, reducing credit availability and increasing credit constraints for firms. This is especially true for credit types with more uncertain repayment capabilities, e.g., new small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with poor credit histories, and firms requiring investment loans with longer maturities and higher uncertainty about the future profits generated by their investments. Overall, the effects of independent and identically distributed shocks may be more protracted if they hit credit markets that are less efficient at dealing with information asymmetries, such as in low- and middle-income countries.

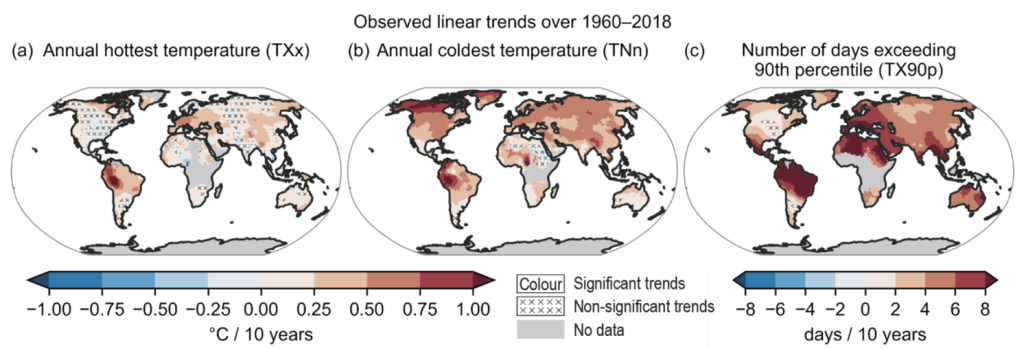

Additionally, it is important to note that warming is not projected to affect countries uniformly. Most developing countries are in regions with high baseline temperatures. Therefore, even uniform warming may have varying impacts due to stringent biological limits on agricultural yields and human health. However, current models project large variations in regional warming, as shown in Figure 2. For all the above reasons, understanding the impacts of extreme weather events on the financial sector in developing countries is of critical policy importance.

Figure 2 Projected changes in annual maximum (panels a–c) and minimum (panels d–f) temperatures for global warming of 1.5°C, 2°C, and 4°C compared to the 1850–1900 baseline.

sauce: IPCC (2021) Figure 11.11.

In our recent study (Aguilar-Gomez et al. 2024), my co-authors and I employ a robust methodology and comprehensive dataset with information on all loans extended by Mexican commercial banks to private firms over almost a decade. This allows us to take a closer look at potential climate vulnerabilities within Mexico’s financial system. Specifically, we focus primarily on delinquency rates, measured as the ratio of non-performing loans to total outstanding credit within a county, and estimate the impact of unexpected days above the 95th percentile of the temperature distribution on firms’ financial distress.

Our study revealed three main findings:

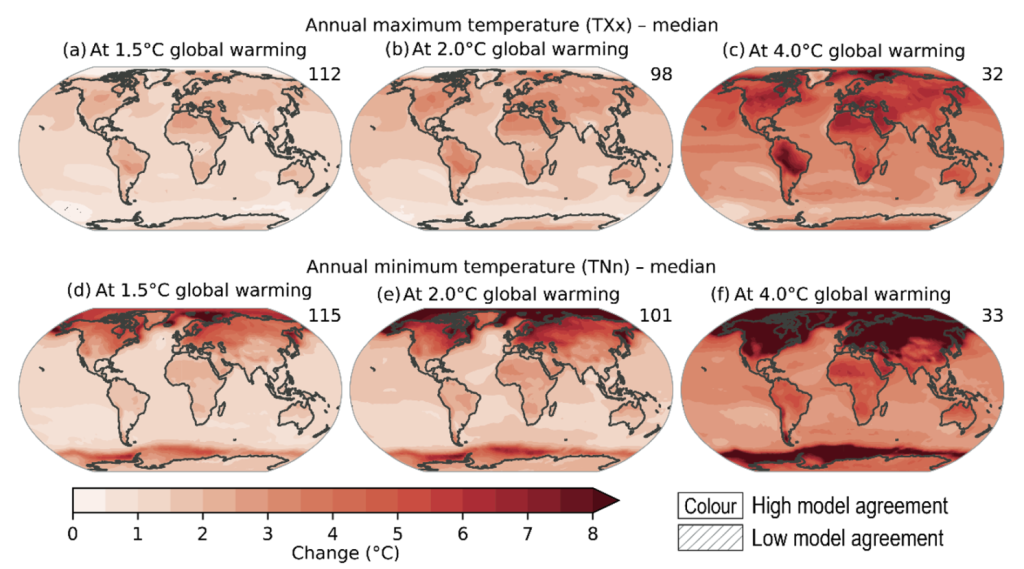

- Credit delinquency rates rise due to heatwaves in municipalitiesan effect entirely driven by SME loan defaults. In terms of magnitude, 10 days of unusually hot weather in the past three months increases SME default rates by 0.17 percentage points, which is equivalent to 4.4% of the observed sample mean (3.9%). Figure 3 illustrates this phenomenon by plotting the relationship between default rates and the number of extremely hot days in the past quarter. It also shows that extreme heat must be long enough (i.e., 11 days) to cause significant damage. This result is consistent with the idea that SMEs in developing countries are less able to cope with extreme temperatures and therefore have more difficulty obtaining further credit during times of financial stress. Consistent with theory and previous studies (e.g., Schlenker and Roberts 2009; Blanc and Schlenker 2017), we find that the negative effects of extreme heat are stronger in agriculture.

- The composition of regional economies mattersExtreme heat also has a large impact on non-farm industries in regions with a sufficiently high proportion of agricultural workers. Moreover, the impact on the non-farm sector is concentrated in services and retail, non-traded sectors that rely heavily on local demand. Our findings suggest that adverse conditions in agriculture lead to reduced local spending, causing spillover effects on non-farm industries.

- By adopting various market integration measures in agricultural production, Weather shocks have a stronger effect on agricultural firms’ credit defaults in more integrated markets.This result is consistent with the idea that higher prices partially offset the decline in local production caused by extreme weather in more isolated markets. Interestingly, this evidence suggests that financial institutions may be less affected by temperature shocks in relatively isolated markets.

- If our data indicates that companies will recover and that short-term shocks will not have long-term effects, we may not need to worry too much about these results. Sudden temperature changes will reduce the number of businesses in affected municipalities that have access to credit for a period of time.Credit composition will change after a climate shock, Reduced credit for investment and new businesses, and higher interest rates on new loansSpecifically, exposure to extreme heat increases interest rates and collateral requirements for new loans within the same firm, reducing access to credit. Combining firm- and market-level results, we find that banks tighten lending over two to three quarters in response to the shock, preventing firms from accessing financial flexibility at a time when they need it most. These findings contrast with those found in developed countries, particularly the United States, where there is evidence suggesting that firms use credit lines to manage liquidity during extreme weather (Brown et al. 2021; Collier et al. 2020). Mexican small and medium-sized enterprises appear to have similarly limited access to new credit.

Figure 3 How extreme temperatures affect delinquency

Our findings provide empirical support for concerns about the potential impacts of extreme weather events on the financial system, as for example stated in Reinders et al. (2023). In response to the accumulating evidence, regulators and central banks around the world are calling for improved measurement and monitoring of climate risks to help actors manage them (Litterman et al. 2020). One policy implication of our findings is that policies that aim to reduce direct exposure to climate shocks in banks’ balance sheets should ideally be implemented in conjunction with other complementary policies, especially in developing countries. Such policies could compensate for unintended consequences by deepening access to credit for small and medium-sized enterprises, especially as they deal with the effects of weather shocks.