Lifelong inflammatory bowel disease affects 1 in 350 people in the UK.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have grown ‘mini-guts’ in the lab to understand and identify the best treatments for people with Crohn’s disease.

Published in a journal IntestineThe researchers used cells from the inflamed intestine to grow more than 300 tiny intestines, called organoids, to better understand the inflammatory state.

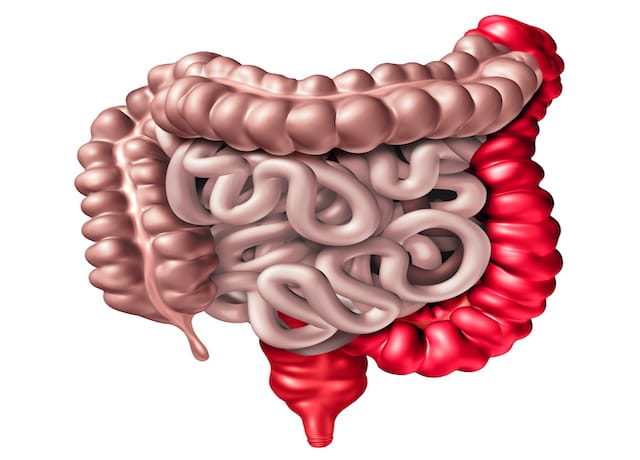

Crohn’s disease is one of two types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a lifelong condition characterised by inflammation of the digestive tract that affects around 1 in 350 people in the UK.

Although there is some evidence that having a direct family history of Crohn’s disease puts an individual at higher risk of developing the disease, it is estimated that only 10% of inheritance is due to DNA mutations.

The researchers grew organoids in their lab at Cambridge University Hospital from inflamed intestinal cells donated by 160 patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (the second most common type of IBD), as well as patients without IBD.

The researchers grew organoids from stem cells taken from the intestine, which mimic key functions of the epithelium that lines the intestine, and showed that epithelium from Crohn’s disease patients had different epigenetic patterns in their DNA (changes to the DNA that activates genes, changing the way cells function) compared to healthy controls.

Furthermore, patients had increased activity of major histocompatibility complex I, a specific pathway by which immune cells recognize antigens and induce inflammation in the intestine.

Matthias Silbauer, professor of paediatric gastroenterology at the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, commented: “Not only were the epigenetic changes different in Crohn’s disease, but there was also a correlation between these changes and the severity of the disease.”

“These changes help explain why not all organoids showed the same epigenetic changes.”

The researchers believe that organoids could be used to develop and test new treatments for people with Crohn’s disease, as well as to customize treatments for individual patients.