in Previous articleI have argued that over 100% of the inflation since late 2019 has been demand-side driven. There have been several supply shocks in 2021-2022 that have led to significant inflation, but there have also been large supply shocks (especially immigration) that have tended to keep inflation down. On a net basis, all of the cumulative inflation has been demand-side driven.

I find nominal GDP growth a useful proxy for demand contributions. Real GDP tends to grow about 2% per year on average, so 4% NGDP growth is a useful benchmark for appropriate monetary policy. Since late 2019, there has been about 11% cumulative excess NGDP growth (i.e., over 4%), which is enough to explain about 9% cumulative excess PCE inflation (over 2%).

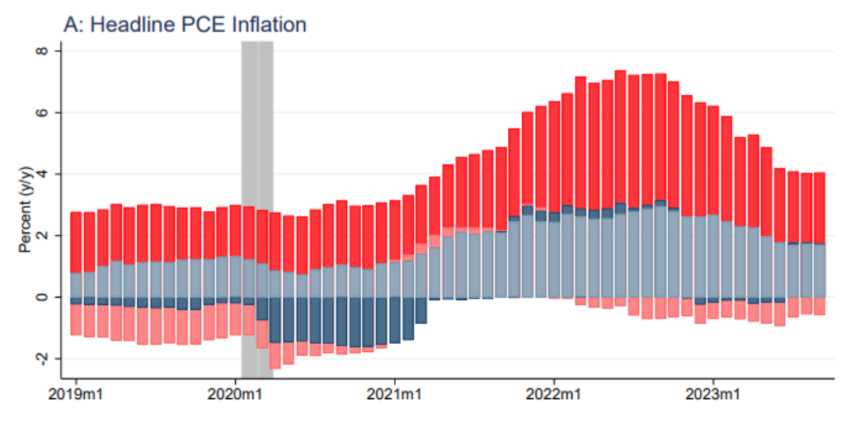

Most economists apparently don’t see things this way. Most economists seem to think that the high inflation from 2020 to 2024 will be the result of a combination of supply and demand shocks. A recent San Francisco Federal Reserve working paper argues: Adam Hale Shapiro It gives a breakdown of supply-side and demand-side inflation, which is pretty consistent with estimates from many economists that I’ve seen.

Note that both negative supply and positive demand shocks play a large role, with negative supply shocks being particularly important for headline inflation (including food and energy prices).

Shapiro uses an interesting methodology to uncover the contributions of demand and supply shocks.

Because inflation is constructed as a weighted sum of category-level inflation rates, it is easy to separate inflation by category, or by groups of categories. I separate each month into categories where prices fluctuated due to unexpected changes in demand and categories where prices fluctuated due to unexpected changes in supply. This method is based on the standard theory of the slopes of supply and demand curves. A change in demand moves both price and quantity in the same direction along an upward-sloping supply curve, while a change in supply moves price and quantity in opposite directions along a downward-sloping demand curve.

To say I have mixed feelings about this is an understatement. I am a strong supporter of looking at price-output correlations to identify demand and supply shocks, but I am strongly opposed to aggregating sectoral price changes to make inferences about aggregate price changes.

One of my First published paper (JPE, 1989, with Steve Silver) looked at real wage cyclicality. They tried to estimate how real wage cyclicality depends on whether the economy was hit by a supply or demand shock. They identified these two types of shocks by looking at periods when prices and employment moved in the same direction (demand shocks) and periods when prices and employment moved in opposite directions (supply shocks). So I am totally in favor of such an identification strategy. You can also compare the change in inflation to the change in real GDP growth. In fact, my view that 2019-2024 is all demand-side inflation is due to the fact that growth was above trend, i.e. both prices and output were moving in the same direction.

Shapiro looks at price and output data for over 100 goods and services. Here’s the part I don’t agree with (or maybe I don’t fully understand): in a complex economy, some markets will have positive correlations between prices and output, and some markets will have negative correlations between prices and output. I worry that this approach overstates the role of supply, because even in an economy where 100% of inflation is demand-driven, individual markets will have negative correlations between prices and output (indicating a supply shock).

Consider a thought experiment in an economy characterized by stable but high rates of inflation, created by rapid monetary growth. Assume also that wages and monetary contracts take inflation into account, because the population is accustomed to rapid inflation; that is, assume that money is roughly neutral. We can imagine an economy in which the money supply doubles every 12 months, and all wages and prices rise at a similar rate. Output is (by assumption) at its natural rate. By assumption, this is an economy in which nearly 100% of inflation is demand-side (due to monetary policy). And yet the correlation between prices and output varies widely across sectors, because various local supply and demand shocks produce all sorts of changes in relative prices. In other words, the factors that affect relative prices in individual markets are fundamentally different from the factors that affect the overall price level (in this case monetary policy, but velocity is another possibility).

Shapiro introduced me to a new study on inflation in Turkey that convinced me that my thought experiment was more than just a hypothetical concern. Before considering their study, let’s consider how much inflation can arise from supply-side factors. If monetary policy causes NGDP to grow by 4%, then if output grows at its 2% trend rate, then inflation will be 2%. But if a supply shock causes output to fall to -1% and NGDP continues to grow at 4%, then inflation will rise to 5%. So there’s no dispute that a supply shock can temporarily cause inflation to rise by 3% above trend. But what would it take for a supply shock to cause a country’s inflation rate to rise by 30% or 50%?

Turkish Studies Okan Akarsu and Emrehan Aktug I created this graph:

Notice that Turkey’s inflation will peak at about 80% in 2022, well above that of the United States. Also note that the proportions attributable to demand and supply shocks are similar to the estimates shown in Shapiro’s graph of headline inflation. You might think this fact is not surprising; the Turkish authors cited Shapiro’s work and used a similar model. However, I would argue that the contribution of supply shocks is In the absolute sense Inflation rates in the two countries are likely to be relatively similar, in the low to mid single digits. Given that Turkey has a monetary policy that generates very high NGDP growth, we would expect almost all of Turkey’s inflation to be demand-side driven.

The summary of the Turkish paper is as follows:

We follow the decomposition methodology of Shapiro (2022) to document the demand- and supply-driven components of inflation in Turkey. Results suggest that the recent inflation rise, which began with the COVID-19 pandemic but deviated significantly from global inflation rates, was initially driven by supply factors but over time has shifted to an inflationary environment driven primarily by demand factors. Consistent with theory, oil supply and exchange rate shocks increase the supply-driven contribution, while monetary policy tightening reduces the demand-driven contribution to inflation. This decomposition could serve as a useful real-time tracker for policymakers.

Perhaps the phrase “exchange rate shock” is one source of disagreement. In my thought experiment where the money supply doubles every year, I assumed that wages and prices also double. And one very important price is the price of foreign exchange, or the “exchange rate.” That is, one year 100 Turkish liras might buy 1 US dollar, but a year later it might be 200, 400, and 800. I suppose this could be considered an “exchange rate shock,” but to me it’s just one aspect of demand-side inflation, which drives up all prices, including the price of foreign exchange.

Our views are so far apart that I think the issue here is terminology. The terms “supply” and “demand” were invented to describe relative price changes in particular markets for goods and services, not to describe overall price changes. There has always been a divide between those who prefer to think of inflation as a decline in the purchasing power of money caused by changes in the demand for and supply of money, and those who think of inflation as the sum of individual price increases caused by supply and demand factors in broad markets. I am on the monetarist side of that divide.

For the concepts I’m interested in, it might be better to use entirely different terminology. Thus, I could use the term “nominal inflation” for variations in the inflation rate that are related to variations in the NGDP growth rate, and “real inflation” for variations in the inflation rate that are caused by changes in real output while holding NGDP constant. Of course, these terms are merely accounting, not causal. I believe that NGDP growth is ultimately determined by monetary policy (including monetary policy errors of omission), but such causal claims require evidence and are not mere tautologies.

Either way, I may be missing something obvious here, and I’m curious how others view assertions such as the estimate that half of Turkey’s 80% inflation in 2022 is supply-side. Do you think that’s plausible, and if so, what’s your definition of “supply-driven”?

I have not seen a clear definition of supply-side inflation vs. demand-side inflation. In the absence of a consensus view, each empirical study on the issue becomes the de facto definition. Perhaps there is no real debate at all, just different definitions.

P.S. Supply Inflation Even lower Lower than my estimate. The argument is that increases in real output tend to push down prices. So if RGDP rises by 2% and NGDP rises by 4%, then, other things being equal, one could argue that the supply side will push down the price level by 2% and the demand side will raise prices by 4%, resulting in a net inflation rate of 2%.