“Germany must remain an anchor of stability in Europe,” Chancellor Olaf Scholz said after his coalition finally passed a budget and headed out for summer recess.

It’s unclear exactly how the coalition erased a roughly 25 billion euro funding gap. They didn’t take the trouble to provide a detailed explanation. (1)

Finance Minister Christian Lindner might have been busy doing other things as he posted a picture of himself toting a Stinger missile during a recent military exercise. (2)

Finanzminister und Major d. R. @c_lindner war gestern mal wieder zur Turbo-Wehrübung bei der #Bundeswehr, genauer gesagt bei der Flugabwehr (@Team_Luftwaffe) in Todendorf. Auf Instagram postete er ein Bild davon: Stinger auf der Schulter, Rolex am Handgelenk. pic.twitter.com/HVBWBrmzs7

— Matthias Gebauer (@gebauerspon) July 12, 2024

Parts of the budget are leaking out however, and it is being reported that the historically unpopular traffic light coalition of the Greens, Social Democratic Party, and Free Democratic Party cut aid to Ukraine and its contribution to the EU, as well as moved some defense purchases off the 2025 budget, but they will have to be accounted for in future budgets by the next government.

Anyone paying attention knows that Scholz is out of mind to invoke the term “stability” for the state of Germany at the moment. Let’s consider the following:

- He leads the most unpopular government in modern German history. Three quarters of the population are dissatisfied. According to a survey conducted July 1-3, zero percent of Germans said they were “fully satisfied” with the ruling coalition’s work. Even accounting for the margin of error, that’s suboptimal.

- The three parties in the ruling coalition are together polling at around only 30 percent, and they were embarrassed in the June European elections. Scholz’s own party, the once-proud Social Democrats, came in at less than 14 percent in the European elections. That is the party’s worst result in a national election since the founding of the Federal Republic in 1949.

- Washington and Berlin just announced that they’re deploying long-range U.S. missiles that could reach Russia (including SM-6, Tomahawk, and at some point probably hypersonic weapons) on German territory from 2026 for the first time since the Cold War in a move that will almost certainly make the country less secure.

- The Russians are everywhere. The recent news that Russia planned to kill the CEO of arms manufacturer Rheinmetall, comes on the heels of the Russians allegedly behind a fire at a metal factory, espionage on Ukrainian targets in Germany, the murder of a Chechen in Berlin, payments to spread Kremlin propaganda, and all types of “information warfare.”

- The German economy has been stagnant for seven years running, which I suppose is a form of stability.

- Meanwhile, the government in Berlin is cutting social spending, German industry “has taken a permanent hit,” real wages have dropped back to 2016 levels, and the government is investing 12.4 billion euros in the stock market in a new “Generation Capital Foundation” as part of a scheme to continue financing pensions. Stability.

- And still no one can figure out who destroyed those Nord Stream pipelines.

Despite Scholz’s stability reassurances, more upheaval is likely in a few months’ time.

“The Big Worry”

If the freak out over a few political parties who favor repairing ties with Russia and who performed well in the European Parliament elections is already at a 10, expect it to be turned up to an 11 should they continue their rise in the polls ahead of September state elections in Saxony, Brandenburg, and Thuringia.

The EU vote clearly sent a loud message about voter dissatisfaction. The upcoming state elections could present challenges for German support for Project Ukraine by heaping more pressure on the country’s ruling coalition that is already on life support.

Some background on the two parties threatening to upset the apple cart: Sahra Wagenknecht’s old-school left Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) focuses on working class issues, ignores identity politics, and opposes the US-led new Cold War.

The other party is of course the ethno-nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD). It wants to reclaim German sovereignty from the EU and NATO and make nice with Russia since that is in German interests. While the party has attracted widespread working class support, detractors like BSW argue it is no friend of the people, but instead favors a different flavor of oligarchs – German rather than global. What really propelled the AfD into prominence is its outspoken opposition to the dramatic increase in immigrants to Germany in recent years.

Remarkable chart, within just a decade net migration into Germany has been 6 Million people. That’s more or less Berlin and Munich combined. Is it sustainable? pic.twitter.com/s8JZAZ8dVx

— Michael A. Arouet (@MichaelAArouet) June 27, 2024

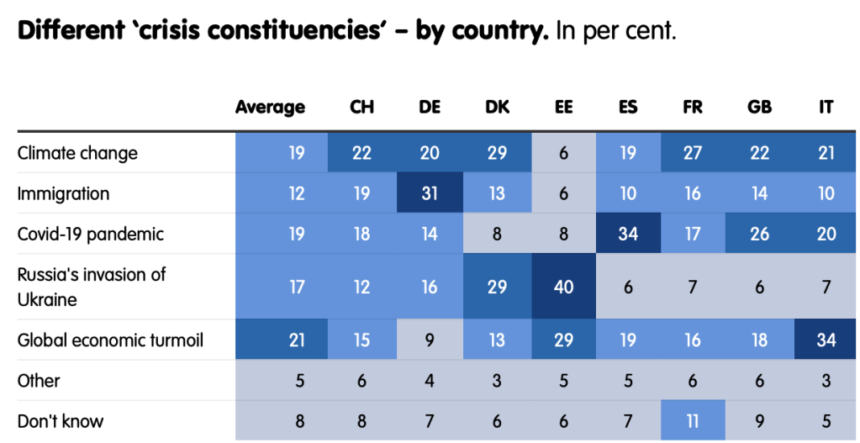

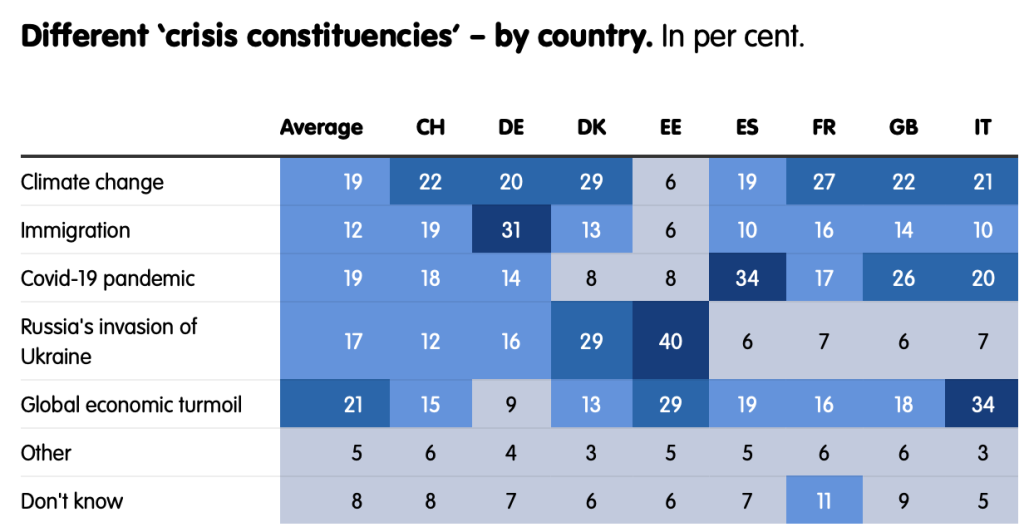

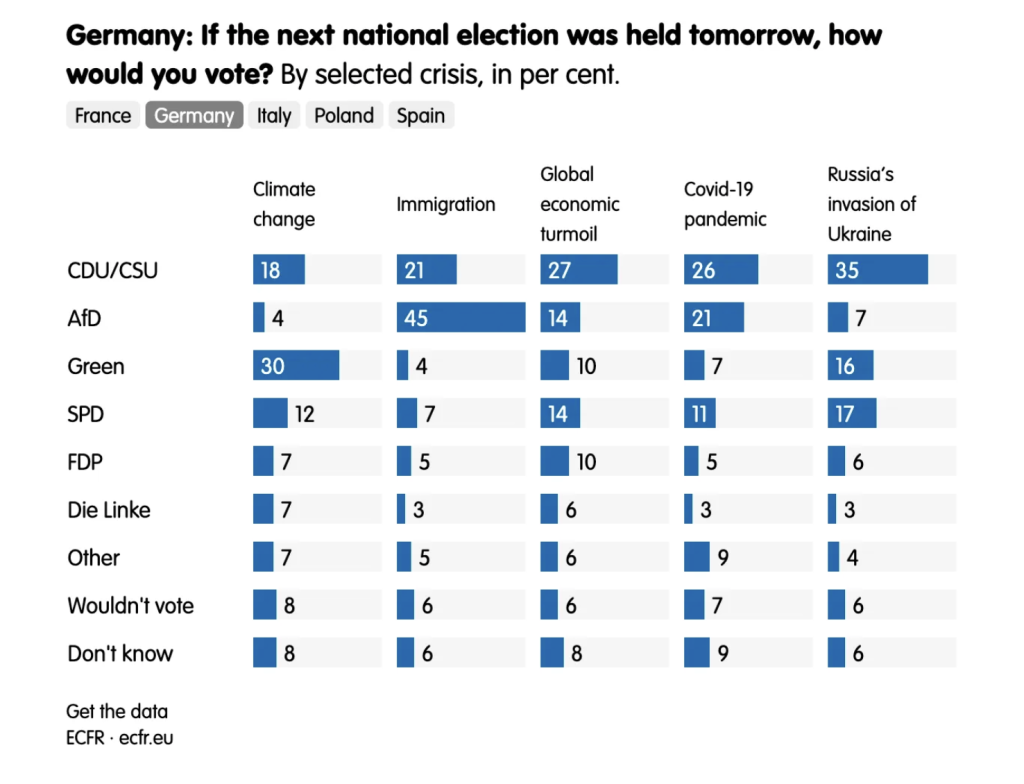

We can see the effect on the electorate:

There is also evidence that a sizable chunk of AfD support is a way to give a raised middle finger to the current political establishment, which is at record-low approval ratings.

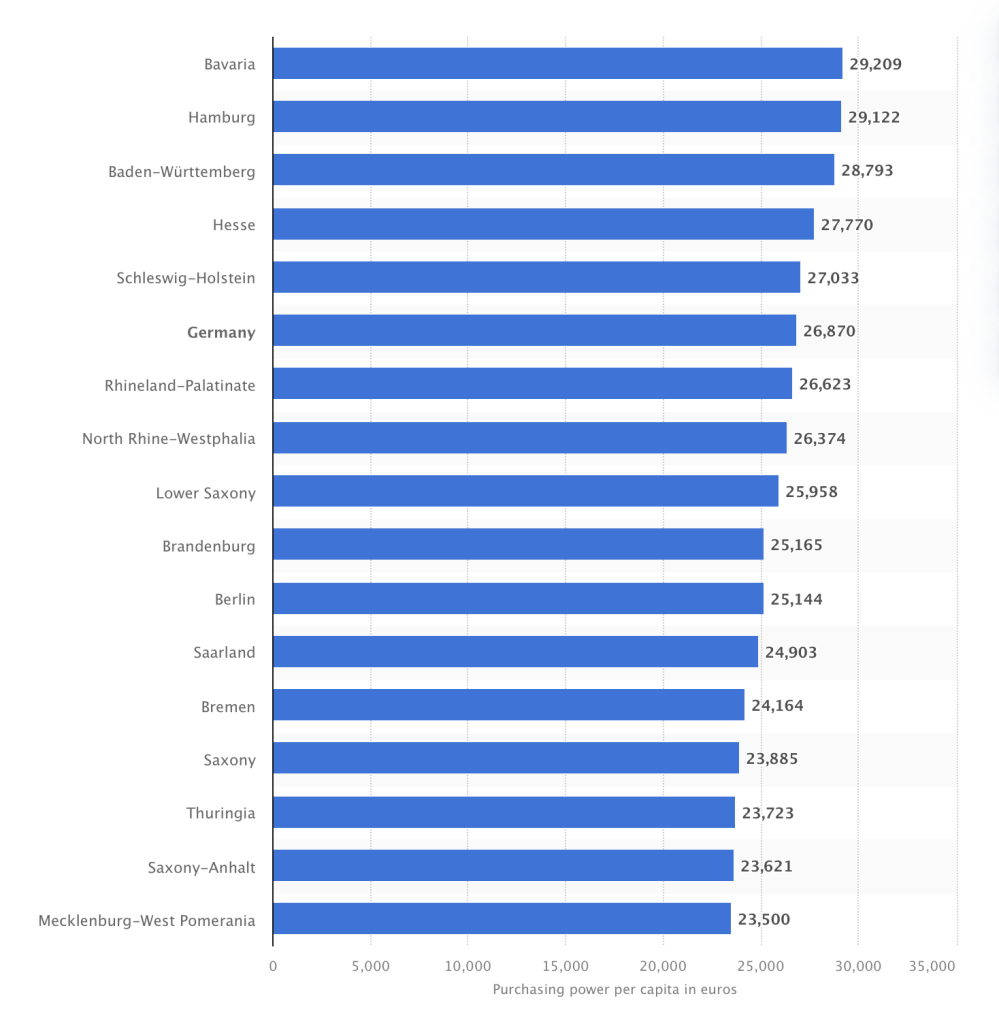

The three states that will be heading to the polls are all former East German states, largely working class with some of the bigger employers in industries like the auto sector, machinery production, and metalworking. The states are on the poorer end when looking at German states:

Source: Statista

Brandenburg (6.1 percent), Thuringia (6.3 percent), and Saxony (6.6 percent) are all a little over the national average unemployment rate of 6 percent.

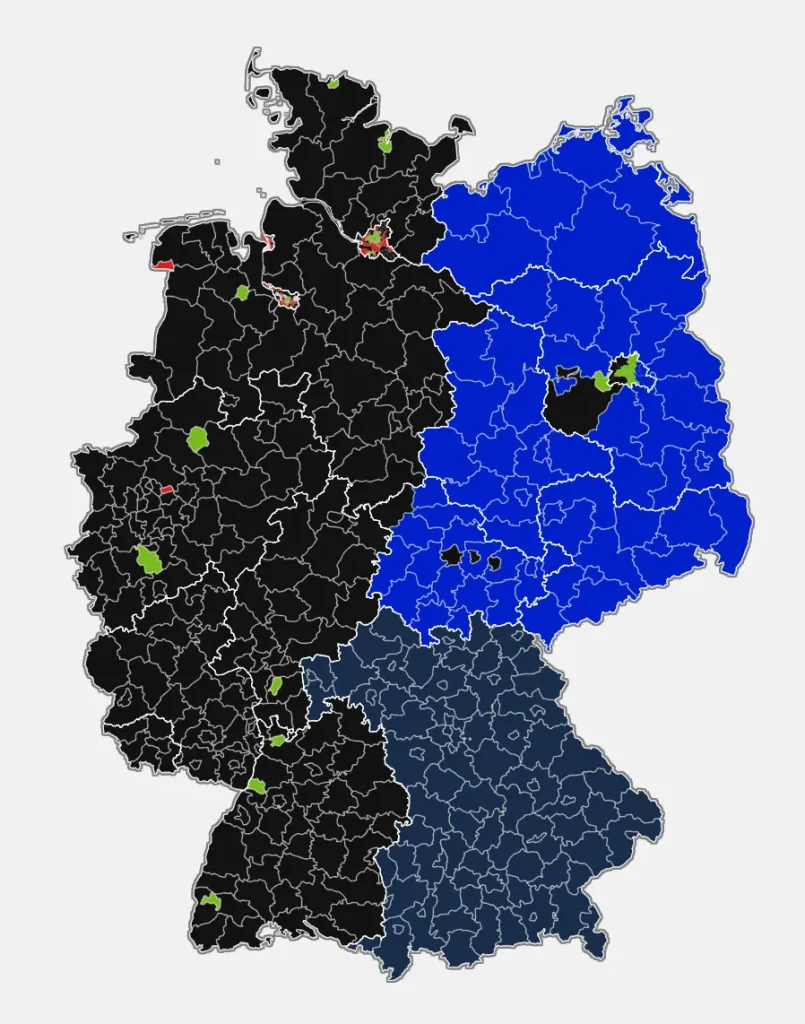

The fact the elections are taking place in eastern Germany is a boon for the AfD and, to a lesser extent, BSW. We can see how well the AfD performed there in the European elections (blue is the AfD while black is the Christian Democratic Union):

According to Manès Weisskircher who researches social movements, political parties, democracy, and the far right at the Institute of Political Science, TU Dresden, AfD’s support in the East can be primarily traced to three factors:

- The neoliberal ‘great transformation,’ which has massively changed the eastern German economy and continues to lead to emigration and anxiety over personal economic prospects.

- An ongoing sense of marginalization among East Germans who feel they have never been fully integrated since reunification and resent liberal immigration policies in this context.

- Deep dissatisfaction with the functioning of the political system and doubt in political participation.

Voters in the East also had other political parties abandon them, such as The Left (Die Linke), which has completely collapsed after abandoning nearly all of its former working class platform in favor of identity politics in an attempt to appear “ready to govern.” Much like the Greens, The Left increasingly stands for neoliberal, pro-war and anti-Russia policies. Former Left voters increasingly switched to the AfD in response.

Wagenknecht abandoned The Left and formed her own party at the beginning of this year. And the essentially one-woman party is already rivaling Scholz’s 150-year-old SPD for support. In the European elections BSW got almost 13 percent in Saxony, 13.8 percent in Brandenburg and 15 percent in Thuringia. BSW still has a ways to go to catch the AfD, however, but if polling is any indication, there is a good chance that following the September elections, the political establishment in these states will likely face a choice: try to align with BSW to maintain the firewall against the AfD or bring the AfD into government.

Here’s a look at current polling in the states:

Those polls are causing blood pressures to rise in Berlin, Brussels, and Washington. SEMAFOR recently summed up the thinking in those locales with a piece titled “The Big Worry.”

In it they try to explain what’s wrong with the voters that they would vote for the AfD or someone like the “pro-Kremlin” Wagenknecht. Naturally, major fault lies with the Russians according to serious people:

The European Parliament election results showed a stark divide between former East and West Germany, with nearly every constituency in the former Eastern bloc going to the far-right AfD, prompting one economist to comment, “Who said that Germany reunified?” An academic from Saxony told The German Review newsletter that despite their support for Russia-friendly parties, “east Germans don’t like Russia. Instead, they learned during the Cold War that it’s better not to provoke the Kremlin.” Analysts had warned of Russian influence campaigns during the European elections to boost support for far-right parties. In eastern Germany, though, support for the AfD’s stance on Russia and migration has become so entrenched that “there is no influence necessary,” political scientist Hans Vorländer told Semafor.

The Senator piece highlights another trend among the entrenched establishment, which is to equate left and right (in this case, BSW and the AfD) as two sides of the same coin:

Jan Rovny, a political sciences professor at Sciences Po, told Semafor. The far left projects a misplaced nostalgia onto Russia as the “carrier of some kind of Soviet heritage,” he argued, while the right see Putin as an emblem of “Christian, traditional, masculinist Europe.” Strikingly, rather than warring against each other, nationalists today view themselves as providing a united bulwark in the face of a perceived common enemy, Rovny said.

It of course has nothing to do with economic realities of German energy policy or the question of whether it’s wise for Germany to wholly submit to being a military outpost for the US with long range weapons pointed at Moscow (and Russian hypersonic missiles pointed at Berlin). SEMAFOR concludes, “The far left and far right wave different colored flags, but are ultimately similar.”

But they’re really not. At all.

Just a few examples:

- BSW proposes a fairer tax system that benefits the working class, such as the demand for an excess profits tax in the industrial sector. The AfD wants to slash taxes across the board, including those that are progressive and serve to redistribute wealth, such as the inheritance tax

- BSW believes in global warming and wants to continue to take climate action but work to soften the economic blow to the working class. The AfD rejects climate science. In its EU election manifesto, it says that the “claim of a threat through human-made climate change” is “CO2 hysterics,” and it would do away with climate laws that reduce prosperity and freedoms.

- BSW wants to strengthen the social safety net. The AfD stresses the limits of the state’s role.

It’s easy to see why lazy analyses lump left and right together. On the issues that really matter to the Atlanticists that infest the bureaucratic and media offices (unquestioning support for Brussels economic policy and for NATO-led war against Russia) the AfD and BSW do hold similar positions. Both are for an end to sanctions on Russia and to weapon deliveries to Ukraine, and getting out from under the thumb of Washington. The fact the parties are vastly different on economic policies for working class voters hardly registers as important. Maybe the Atlanticists have been so busy for so long trying to equate WWII-era Nazism and communism, it all just comes naturally.

Regardless, what’s clear in these analyses and ongoing lack of any government response to voter concerns is the belief that it is the voters who must change. Who must stop being so backwards, so stupid, and desirous of things they cannot have.

Asked after his party’s embarrassing results in the European elections if he would like to comment on his humiliating defeat Chancellor Scholz said nothing about hearing the concerns of the voters and promising to address those concerns. He simply replied with a defiant “nope.”

And that pretty much sums up where Germany is at the moment. The democratic system has partially broken down as voters make demands and the elected leaders simply say no. Scholz’s foreign minister Annalena Baerbock was more forthcoming in her infamous 2022 comments:

Speaking of Baerbock, she might have taken the satirical cake when she recently took herself out of the running for chancellor next year. The reason? She said the world needs “more diplomacy, not less,” which might sound odd coming from someone notorious for their lack of diplomacy but fits in perfectly with the current government.

Unsurprisingly voters are looking for alternatives.

AfD Prepares to Break Through the Firewall

What else can they throw at the AfD at this point – aside from a complete ban on the party, which could throw Germany into chaos? That possibility remains on the table, and the recent use of a reported 200 masked police officers to raid the office and home of the rightwing Compact Magazine publisher is not a great sign.

The AfD is routinely pilloried in the media. The Nazi comparisons have been repeated endlessly, often for good reason as AfD members just can’t help themselves from admiring the Third Reich such as AfD’s top European Parliament election candidate, Maximilian Krah, who had to step back from campaigning in May after saying that not all Nazi SS members were criminals. There are plenty of other examples, as well.

The party is already under state surveillance.

Spy and corruption cases involving AfD members broke ahead of the European vote.

Despite all that, the party ended up scoring its best nationwide result so far in June, coming second on 15.9% in the European Parliament election.Their next mission is to start breaking down the firewall in Germany that aims to keep the party out of any governments.

“The firewall has already disappeared more or less on a communal level,” Joerg Urban, head of the AfD in Saxony, told Reuters. “The state level is the next step.”

Originally more of an anti-EU party and refuge for neo-Nazis, the AfD has been able to ride the wave of backlash against government policies that have been disastrous for working people – from the war in Ukraine and a losing sanction war to disastrous energy policies that hit poorer people the hardest to a large increase in immigration at the same time standards of living decline. It is now widely seen by its supporters as a party that will “save” German culture and return the country to fondly remembered days – whether 10 years ago or 85.

Yet the mainstream parties in Germany lack credibility when criticizing the AfD’s ethno nationalism when they also support genocide in Palestine policies, which could include a swift increase in deportations, and are simultaneously taking a much harder line against immigrants in an effort to thwart to the AfD’s rise. Earlier this year the Bundestag passed the Repatriation Improvement Act, which increases the amount of time the state can detain someone before deporting them from 10 to 28 days. It also gives the state more powers to enter homes, makes the suspicion of certain criminal offenses enough to deport people, and criminalizes certain activities by aid workers who assist asylum seekers, punishable with up to ten years in prison.

It’s an open question as to whether the backlash against the increase in immigration to Germany would be such an issue if it wasn’t coming at a time of budget cuts and sinking standard of living. Regardless, the path chosen by the current government, as well as the one favored by the AfD, is to punish immigrants rather than try to improve living standards.

Will Anyone Truly Represent the Working Class?

Scholz’s coalition hovers around the 10 percent mark across much of Eastern Germany. If he is presiding over the final nail in the coffin of the SPD after a half century of decline accelerated by abandoning the working class, Wagenknecht is working to take the place it (and Die Linke) once occupied.

The problem is, it turns out she’s in more of a battle with the AfD. (3) Scholz’s party suddenly has no real base of which to speak. Just above 18 percent of unionized Germans voted for the SPD in the European election compared to 18.5 for the AfD. Adam Tooze elaborates:

Germans who feel well off are twice as likely to vote Green or FDP than those feeling that they are doing badly. But the SPD too scores 36 percent better amongst Germans who judge themselves to be living well as opposed to those who feel hard-up. The parties whose support tilts the other way are in the opposition: Wagenknecht’s group and the AfD. Support for the AfD is two and a half times larger amongst Germans who judged themselves to be hard up than amongst those who consider themselves well off.

And as Tooze detailed in his detailed breakdown of Germany’s vote for the European Parliament, ‘the real opposition in German society and political preferences is not between the “old” labour movement and the AfD. The real juxtaposition is between the AfD and the Greens.’

The CDU might lead in the national polls and is likely to head the next government, but the Greens and the AfD best represent the ideological forces pitted against one another in Germany. One is a globalist, neoliberal, bourgeoisie, pro-war, pro-NATO party that favors immigration. The other is sovereignist, ethno-nationalist, favors a more national oligarchy, has increasing support of the working class (despite a lack of policy proposals that would benefit workers), and is not opposed to war but insists it be in German interests not Washington.

BSW is trying to crash that party. The September votes in three eastern states could provide a major boost.

As we can see, the German electorate is in a state of flux, driven by the upheaval in the country and the deep dissatisfaction with the ruling coalition. There isn’t a neat way to explain the migration of voters aside from possibly anger. Recent polling shows that 87 percent of AfD voters think the current government should be sent a reprimand; 71 percent of Wagenknecht voters agreed. And both parties are picking up voters from other parties regardless of ideology:

Wagenknecht’s supporters rank peace and the war in Ukraine as their primary concern, and she continues to hammer home her opposition to the conflict, as well as the recent decision to deploy long range US missiles in Germany. Their second biggest concern is immigration. Wagenknecht, born in East Germany to German and Iranian parents, doesn’t want to limit immigration for ethno nationalist reasons like the AfD, but her position can be summed up by her response to a question regarding the issue here:

We don’t think a neoliberal immigration regime, where everybody can in effect go anywhere and then must somehow try to fit in and survive, is a good idea. We need to welcome people who want to work and live in our country and we should learn to do so. But this shouldn’t result in disrupting the lives of those who already live here, and it shouldn’t overstrain collective resources, for which people have worked and paid taxes. Otherwise, the rise of nativist right-wing politics will be inevitable. In fact, the AfD in its present form is largely a legacy of Angela Merkel. In Germany we have a dramatic housing shortage, especially for people with low incomes, and the quality of education in public schools has become appalling in places. Our capacity to give immigrants a chance of equal participation in our economy and society is not endless.

The problem for Wagenknecht remains that Germans rate immigration as their top issue and most trust the AfD. And this brings us to the center of Germany’s democratic breakdown. It would have been hard for the current and past governments to have done a better job promoting the AfD if it had tried.

The rapid influx of millions of immigrants coupled with a stagnating economy, unaffordable housing, and cuts in social services is a recipe for disaster. And so we now have the AfD, which received its seed money from a reclusive billionaire descendant of prominent Nazis, poised to win state elections despite numerous comments by party officials showing at best a lack of understanding about Nazi crimes and at worst an admiration for them while they also argue that Muslims and others are “incompatible” with German culture.

The assist isn’t just from Berlin, either. Voters might be left to wonder what’s so wrong with the AfD when the “responsible” political center in Brussels and Washington backs Nazis in Ukraine, rehabilitates Nazis, enacts mass censorship and other crackdowns, supports genocide, and generally drags us kicking and screaming into their neoliberal fascist vision of the future. And make no doubt about it, should the AfD gradually learn to toe the NATO and EU line, it would no doubt be welcomed with open arms into the halls of power regardless of any admiration for the SS.

Is it worth casting a vote for the AfD, despite its considerable baggage, because the party favors returning sovereignty to Germany, which could help bring about the demise of the EU and NATO? The problem with that rationale is the BSW option, which offers the same opposition to Project Ukraine and NATO as the AfD without any of the fondness for Nazis and a better platform for the working class, so maybe that answers the question.

More broadly, the easy way to defeat a party like the AfD is to give voters material benefits that improve their quality of life; instead we have the opposite happening, and to add insult to injury, voters are insulted as racists for seeking alternatives while their standard of living declines and the “center” plugs its ears and insists on “stability.”

Notes

(1)The coalition has been fighting over the 2025 budget following last fall’s rebuke by the constitutional court, placing strict limits on releasing the country’s debt brake. That rule, intended to force governments to balance the federal budget, was introduced under Angela Merkel during the euro crisis and restricts deficit spending to a minimum, except under “extraordinary” circumstances, such as a natural disaster or war. The court apparently did not believe that the war against Russia is as extraordinary as politicians and the press make it out to be.

(2) Lindner’s celebration of military hardware is part of an ominous trend. CDU leader and Germany’s likely future chancellor Friedrich Merz donned a G-suit and hopped into a Eurofighter last month.

(3) The working class divided between an ethno nationalist party and a genuine populist one is not a bad outcome for the Davos crowd at the end of the day as CDU head and former Blackrock Germany executive Friedrich Merz is the odds-on favorite to become the next chancellor.