Yves: This factory-building trend noted by Wolf Richter is worth noting. It’s concrete evidence that serious efforts are underway to “reshoring” manufacturing (pun intended). But willingness and spending don’t always translate to results. Think of the highly publicized Foxconn plant in Wisconsin, which siphoned off huge amounts of subsidies from the state and then deferred them. From CNBC in 2021:

Taiwanese electronics maker Foxconn is drastically scaling back plans for a $10 billion factory in Wisconsin.

Under the agreement, Foxconn will cut its investment plans from $10 billion to $672 million and reduce the number of new jobs from 13,000 to 1,454.

And remember, Foxconn is an established company that knows how to set up and run factories — not some American desperately searching for badly needed factory foremen and senior production managers.

Wisconsin at least restructured the contract and restored many of its grant commitments.

Similarly, Alexander Mercouris has written at length about the failed US efforts to increase production of 155mm shells. In addition to the many accidents he describes at length, the bottleneck remains a shortage of gunpowder. There appears to be only one factory making TNT, in Poland. The US decided to stop using TNT because of its negative environmental impact, but the replacements did not work (it is unclear whether they failed as an explosive or were too difficult to produce on a large scale and/or at a reasonable cost).

Admittedly, it’s a somewhat different type of manufacturing, but I’m a paper mill kid and my father ran a paper mill too, and coated paper is very tricky to work with. In my father’s day we coated it with mineral clay, and the coating is applied while the paper is wet. Paper machines have to operate to very close tolerances or the paper will tear and you’ll have costly downtime.

Due to high capital costs, factories need to operate 24/7, except for scheduled maintenance.

My father did what no one else in his industry could do: start and turn around businesses, eventually becoming head of manufacturing for a major paper company.

The rule of thumb was that a successful startup (a single “machine” like a production line that cost about $500 million in the 1970s) took 2 years and cost 20% of the cost of capital. A failed startup was always a waste of money.

So, building the factory building is the easy part – notice how high your opening success rate and production rate is.

Wolf Richter, editor Wolf Street. Originally Wolf Street

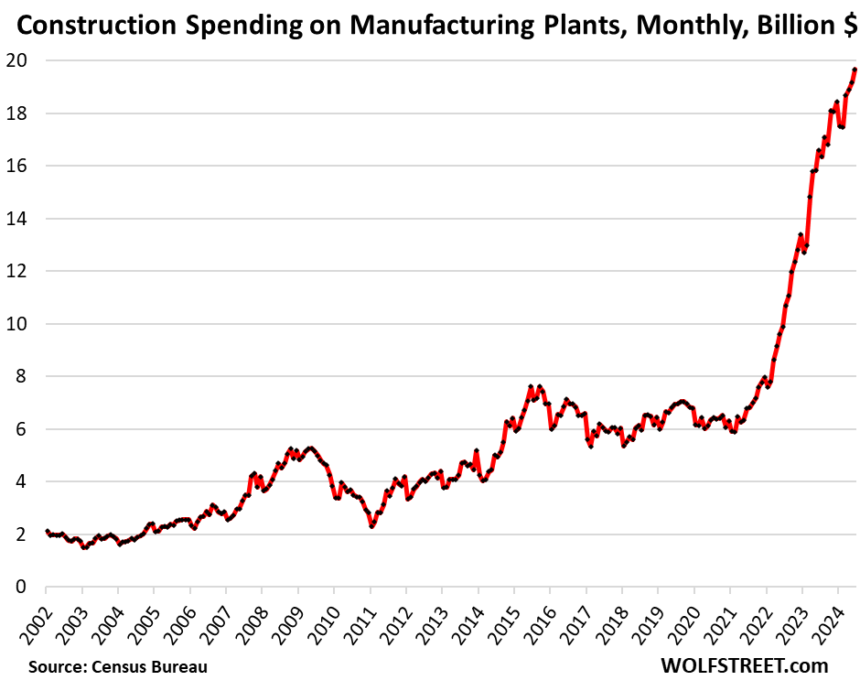

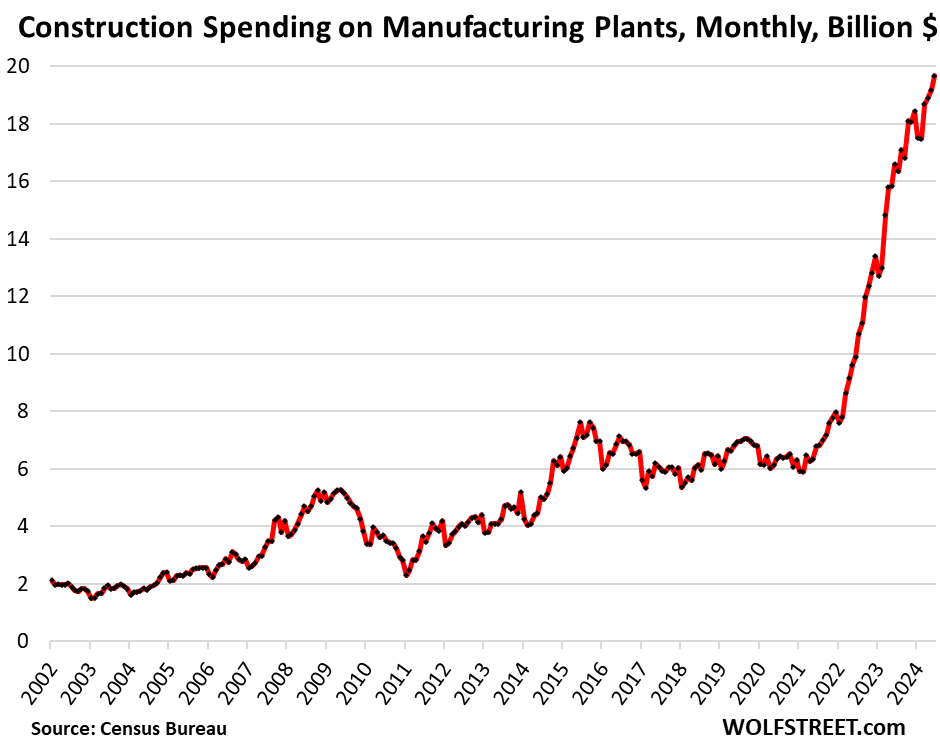

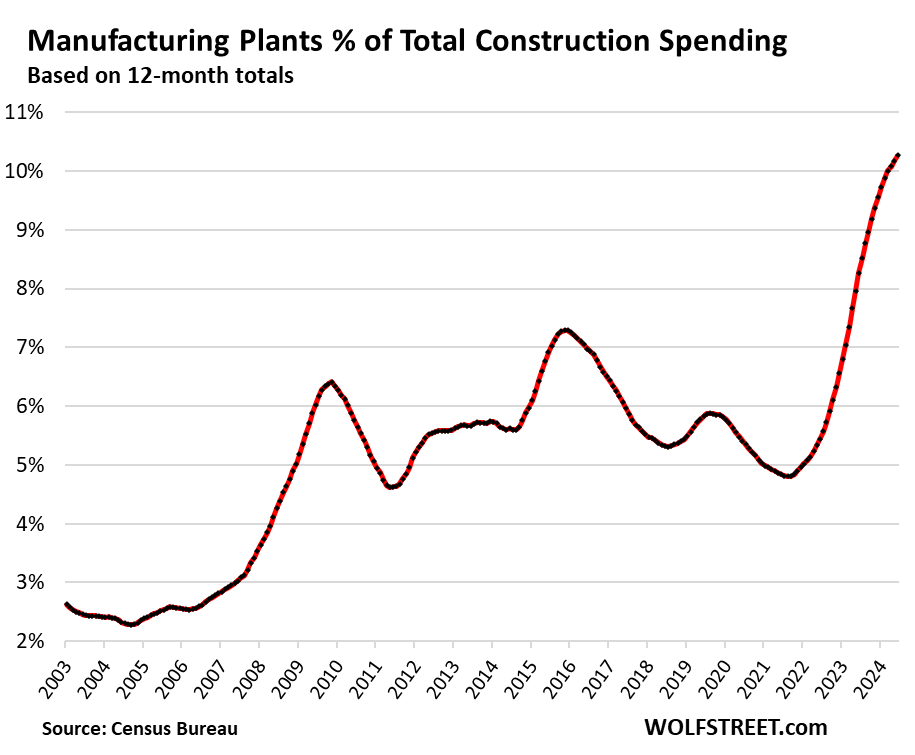

Businesses invested a record $19.7 billion in construction of manufacturing facilities in June, up 18.6% from already-surging June 2023 figures, up nearly 100% from June 2022 figures, and up 209% from June 2019 figures, the Census Bureau reported today.

The total investment here only covers the actual construction costs of the facility, not the cost of manufacturing equipment and facilities, which far exceed the cost of constructing the building. The total cost of a large chip factory can reach $20 billion, but construction costs are the smallest part of that. Thus, the total investment in a manufacturing factory, including equipment and facilities, is much higher. However, the amount here only refers to the construction of the factory and can be seen as an indication of the direction of total investment in manufacturing.

In addition to the booming construction of semiconductor factories, a number of other manufacturing plants have been announced, with more expected to be announced in the future.

The explosion in factory construction that began in the second half of 2021 is one of several changes resulting from the pandemic that has revealed America’s dire dependence on China — massive shortages of all kinds of goods, including semiconductor shortages, and incredible disruptions to supply chains and transportation — and has caused American companies and policymakers to rethink their strategies of endless globalization.

The CHIPS Act, signed into law in August 2022, is part of this movement. The first cash prizes have been announced, but there is still a lot of due diligence and work to be done, and the cash has not yet been paid out. That is still to come.

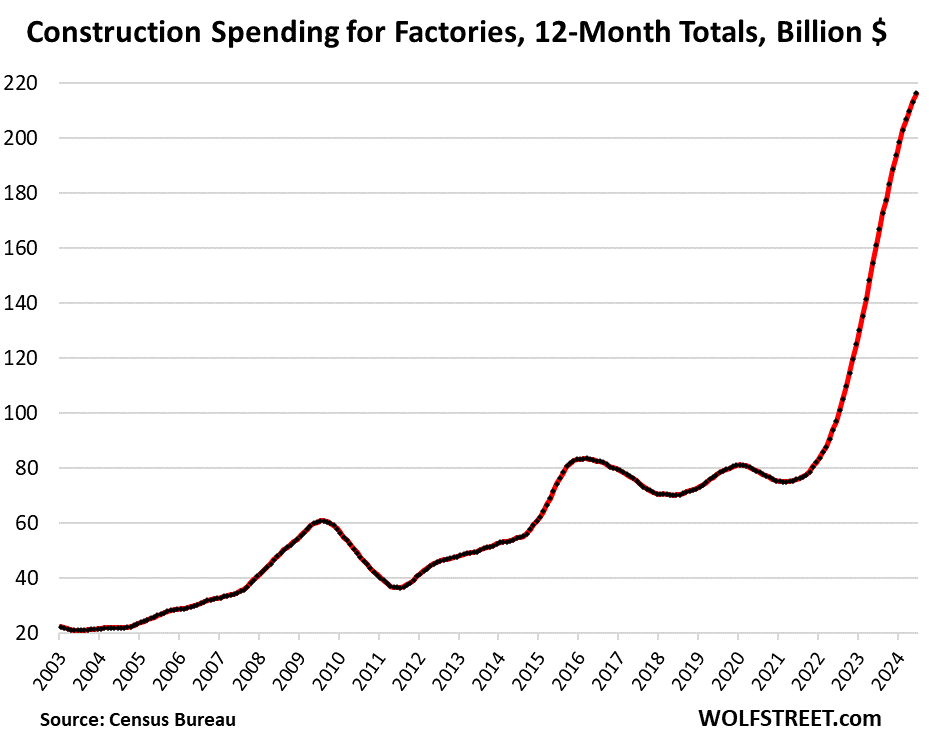

Total investment in manufacturing plants over the past 12 months surged to $235.5 billion, up 19% from the same period last year, 100% from two years ago, and 217% from the same period in 2019.

Construction spending on manufacturing facilities currently accounts for more than 10 percent of total U.S. construction spending, including residential and nonresidential projects ranging from single-family homes to roads and power plants.

This is all based on the principles that the cost of industrial robots is the same in the US and China, that the cost element of manual labor is much smaller in modern automated manufacturing, and that transportation costs (which have skyrocketed during the pandemic), loss of intellectual property (IP) which is a given in China, and other risks must be added to the cost calculation.

Moreover, the increasingly complex and tense relationship between the United States and China has made it clear to everyone that U.S. companies’ reckless reliance on manufacturing in China poses fundamental risks not only to the companies themselves but also to national security.

Companies aren’t building factories in the U.S. to make low-value products like T-shirts. They’re focusing on complex, high-value products like cars, chips, electrical and electronic products, and heavy parts and equipment.

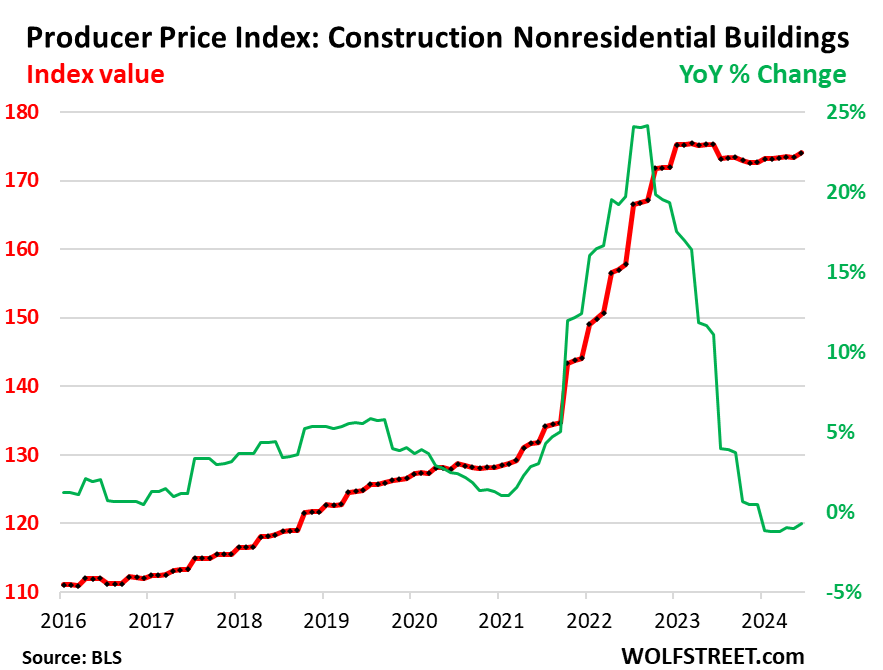

Inflation in the construction industry eases

The Producer Price Index for nonresidential building construction costs rose sharply from mid-2021 through 2022, before leveling off in early 2023 and remaining roughly flat thereafter (red in the graph below).

On a year-over-year basis, the Producer Price Index for Nonresidential Construction is projected to rise by as much as 24% in mid-2022 (green), before trending flat to slightly negative starting in the second half of 2023.