Hi, I’m Yves. This article looks at the issue of what to do about a baby boom in rich countries from an economic perspective, but unlike many other articles, it takes seriously the issue of how to adapt to a stagnant or declining population. It proposes heavy investments to increase national productivity, with a particular focus on education. It also recommends improving healthcare and allowing flexible working for older people, and of course includes the usual cliche of better child care.

It is notable that many of these policies are at odds with default behaviors under neoliberalism, particularly in transforming schooling and health care into opportunities for predation.

by David BloomMichael Kuhn, and Klaus Plettner. VoxEU

Fertility rates have been declining in high-income countries for decades. This trend, along with increasing human lifespan, poses a challenge for developed countries. This column argues that comprehensive policies can be implemented to address economic risks. These policies should stimulate human capital accumulation and education, which are more important than population size for economic prosperity. Furthermore, policies should promote healthy aging and expanding retirement options, and enact family-friendly policies to slow the decline in fertility rates.

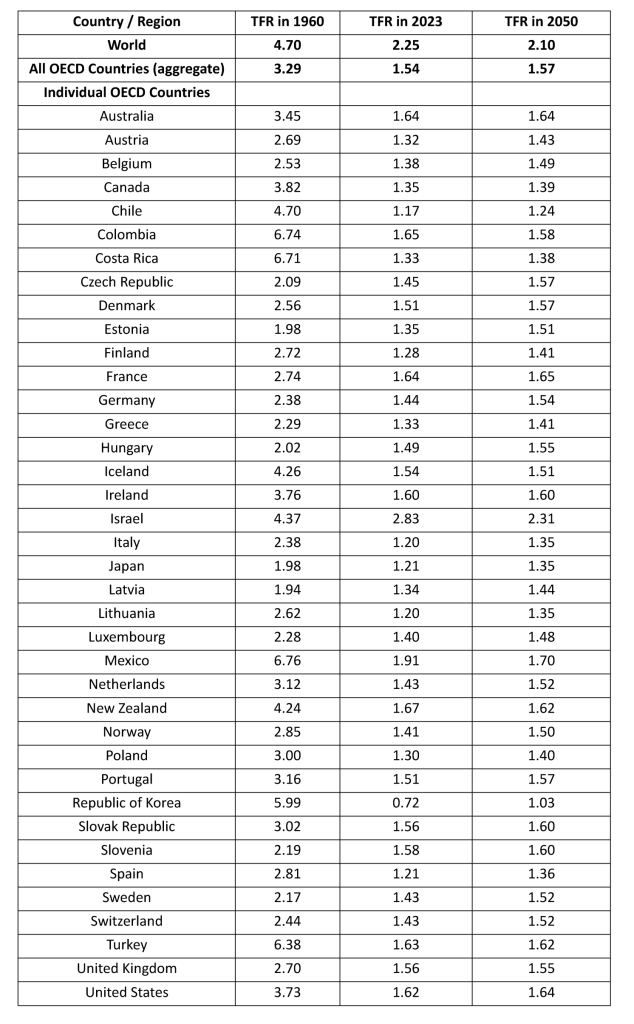

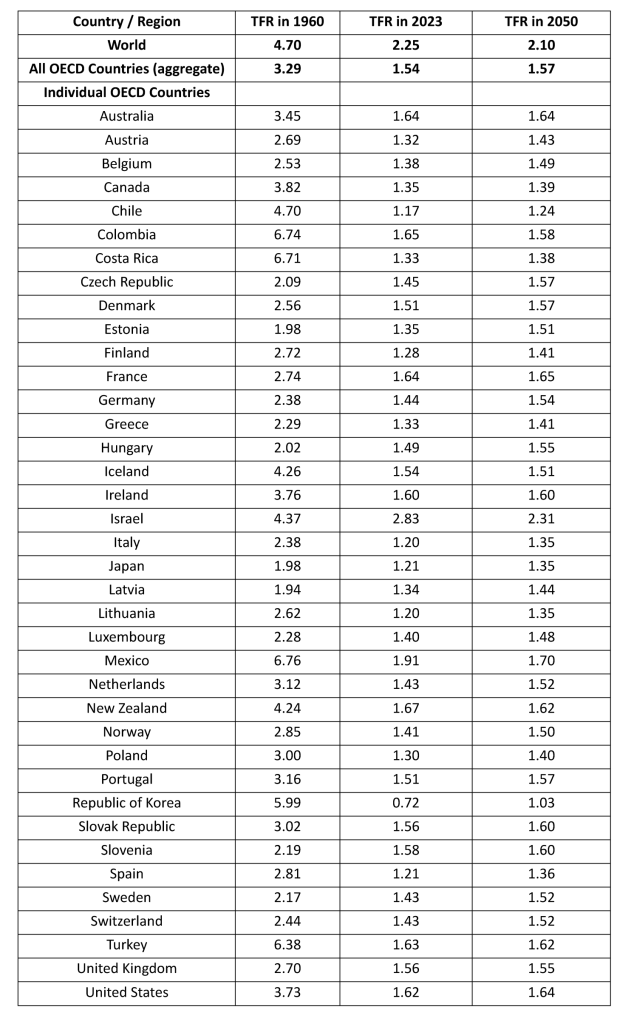

Fertility rates have been declining in high-income countries for decades. Between 1960 and 2023, total fertility rates (TFR, the number of children expected per woman in her lifetime given current age-specific fertility rates) in OECD countries fell by more than half, from 3.29 to 1.54 children per woman (United Nations 2024a). In all but one of the 38 OECD countries (Israel being the exception), the TFR is now well below the long-term replacement rate of around 2.1, implying a long-term trend of contraction in the total and working-age populations (see Table 1).

Table 1 Total fertility rates (TFR) for OECD countries and the world in 1960, 2023 and 2050

sauce: United Nations (2024a); for TFR estimates and (medium-case scenario) projection methodology, see also United Nations (2024b).

In “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of Population Decline,” Charles Jones argues that “significant consequences” of low birth rates include an increasing scarcity of new ideas, which may in effect stifle innovation and lead to long-term economic stagnation (Jones 2022). He points out that multiple models of economic growth place innovation at the center, and that the larger the population with a larger absolute number of researchers, scientists, and inventors, i.e., the more people who work on (breakthrough) discoveries, the more likely they are to achieve more (and more important) discoveries. Jones proposes a model in which population decline leads to an “empty planet” scenario (Bricker and Ibbitson 2019), in which “knowledge and living standards stagnate in the face of a gradually disappearing population.” Jones contrasts this outcome with what he calls the “expanding universe,” an outcome of continued population growth and rising living standards (Jones 2022). “Can quality of people substitute for quantity of people in generating ideas?” Jones muses in a paper for the Stanford Graduate School of Business. “Fundamentally, the answer is no: if the population is declining to zero, it is unlikely that one well-educated person can replace a billion people, including Einstein, Edison and Jennifer Doudna” (Gilson 2022). Jones acknowledges that automation and artificial intelligence could help maintain or improve living standards by spreading scientific progress, but the central question in the title of his paper suggests an ominous sign for falling birth rates (Jones 2022).

In our recent paper (Bloom et al. 2024), we review data and ideas about the historically unprecedented declines in fertility that characterize wealthy industrialized countries today. We acknowledge that declining fertility can stifle innovation. But we argue that behavioral, technological, policy, and institutional changes can affect fertility and the workforce decline, and the economic impacts of fertility itself.

Innovation is certainly a driver of economic development, but it does not depend only on population size. Human capital – the skills and abilities that people possess that enhance their ability to produce valuable goods and services – is also key to innovation. Another fundamental characteristic of human capital is that it can be purposefully accumulated, usually through investments in schooling, job training, and health.

For example, education is a well-established determinant of macroeconomic performance and economic well-being. Education also tends to expand naturally in low fertility contexts, leveraging broader and deeper investments in knowledge and skills among smaller cohorts. Thus, lower fertility rates increase a population’s capacity to innovate and generate more value through work, promoting both individual and societal well-being (Lee and Mason 2010, Prettner et al. 2013). Other things being equal, smaller birth cohorts also benefit population health.

History and rigorous research have shown that the productive characteristics of a population are more significant than population size in defining a country’s capacity for knowledge creation and innovation. The number of healthy, well-educated people (not to be confused with population size) represents human capital that maps squarely to the knowledge production function as a fundamental determinant of technological progress and economic growth.

Oded Galois’s latest book, The Journey of Mankind: The Origin of Wealth Central to the book is the argument that falling birth rates and rising education levels (and the associated technological progress) that lead to the formation of human capital are core to long-term increases in economic prosperity. Falling birth rates have eased population pressures, leading to the accumulation of human capital and dramatic increases in living standards, Galor points out, with life expectancy doubling and per capita income soaring 14-fold around the world since the 19th century.

Falling fertility rates also lead to lower youth dependency ratios in the short and medium term, which can further accelerate the economic growth process by naturally boosting labor force participation, savings and capital accumulation rates. This increase is known as the demographic dividend (Bloom et al. 2003) and boosted per capita income growth rates in many countries by up to 2-3 percentage points after the end of the baby boom that followed World War II. Thus, the downward trend in fertility rates in high-income countries from the 1950s to the present has promoted rather than hindered economic activity and raised living standards.

Declining fertility rates are compounded by the fact that a growing proportion of the population is elderly. Because older people bear a greater burden in public expenditures on health care, long-term care, and economic security, and because they tend to work fewer hours than younger generations, an ageing population can naturally impede economic activity. Nevertheless, it is possible to adapt socially and economically to these demographic realities.

Retirement policy reform is one such adaptation (Kuhn and Prettner 2023). Such reforms have great potential to forestall labor force decline by removing the disincentives to working longer faced by people who are living longer. This strategy represents a way in which policies related to declining fertility may be more effective together than in isolation. By investing heavily in the health and education of a relatively small cohort of young and prime-age adults, it is possible that when that cohort reaches older age, they will be healthy and well-trained enough to work productively beyond traditional retirement age. As we are in the midst of the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing, some frequently asked questions remain relevant: Are we simply living longer, or are we also living longer (Bloom 2019)? Policies that promote healthy ageing, coupled with increased retirement options, could mitigate mounting pressures on pension and health systems and the accelerating demand for long-term care associated with population ageing (Bloom 2022). Stakeholders could therefore benefit from combining synergistic policy initiatives to increase their effectiveness.

Public and private policymakers have a number of family-friendly policies that could slow or reverse the decline in fertility rates. Aimed at balancing work and family responsibilities, these policies include tax cuts for large families, extended parental leave, and, according to Doepke et al. (2023), most effective public and/or subsidized child care. Of course, if such policies achieve their objectives, the short- and medium-term consequence is rising youth dependency ratios, and it will be about two decades before the size of the workforce begins to expand.

Policy decisions need to keep in mind changes in the working world, including digitalization, robotics, automation, and the rise of artificial intelligence (see Prettner and Bloom 2020). While these tools hold compelling potential, these evolutions will not only affect the types of work available and how it is performed (and what is produced and consumed), but also the way workers socialize. This is likely to have major implications for dating and partner selection, and the impact on fertility rates and patterns is as yet unknown.

Thoughtful policy changes should be holistic, recognising social and political impacts as well as economic consequences. Policies to mitigate or limit international migration can be destabilising within or across countries, depending on contextual factors, with implications for social and economic equality. Additionally, the environmental impacts of low fertility rates must be considered. Reducing the number of high-income earners can slow or speed up the pace of climate change, depending on whether it reduces or increases greenhouse gas emissions.

Low and declining fertility rates are an undeniable reality in high-income countries around the world. Given the great uncertainty surrounding the nature and magnitude of its associated economic impacts, it would be unwise to ignore the alarming bells of low fertility rates, especially when they are coupled with another major demographic trend: increased human lifespan. But demography is not destiny. Decreasing fertility rates, and their impact on population size and composition, pose serious challenges, but they are not insurmountable. Humanity has an admirable track record of identifying and capitalizing on opportunities that face us. In this context, there are multiple mechanisms to combat low fertility and address its economic impacts. The time is ripe to launch a rapid and holistic response to identify and implement the most promising policy measures.

look Original Post References