The volume of critical coverage of China’s proposed digital ID system in Western media stands in stark contrast to the near-total absence of coverage, critical or otherwise, of digital ID systems being developed by Western governments.

China is in the process of rolling out a centralised digital identity system, and is doing so as swiftly as possible. One of the reasons I know this is that articles warning about it have been sprouting up across the English-language media landscape. Time magazine, New York Times, the Financial Times, The Economist and the US government-funded Radio Free Asia have all covered the story in the past couple of weeks. The West-adjacent Japan Times has also run an article warning about the “fears of overreach” China’s proposed digital ID system is stoking.

The reason this is unusual is that the dark side of digital identity is a subject the mainstream media in West generally gives the widest possible berth. It is about as close to a taboo subject as you are likely to find, for reasons I will endeavour to explain later. But this being China, everything, including even this, is apparently fair game.

Protecting the Public from Private-Sector Data Abuse (Allegedly)

The articles began appearing a couple of weeks ago when Beijing announced pilot tests for a new national digital identification system across more than 80 internet service applications — only a week after releasing the draft rules for public comment. The draft provision remains open to public feedback until August 25.

According to the government, the main goal of the new system is to rein in data collection (and potential abuse) by the aforementioned commercial apps. It is true that Beijing has for some time expressed concern about the potential data abuses of private-sector tech companies. In 2021, China’s internet watchdog named and shamed 105 apps for data use violations, including ByteDance Ltd’s Douyin and Microsoft Corp.’s LinkedIn.

Beijing’s proposed digital ID system will form part of the broader “RealDID” program that aims to store individual identity records on the country’s government-run Blockchain-based Service Network (BSN). So, in a manner of speaking this is about bringing private data under greater public control. As posits a 2022 review of the book, Surveillance State, in MIT Technology Review, what the Chinese government is doing is redrawing the position of the state and citizens on the same side of the privacy battle against private companies:

As (the book’s authors, Josh) Chin and (Liza) Lin observe, the Chinese government is now proposing that by collecting every Chinese citizen’s data extensively, it can find out what the people want (without giving them votes) and build a society that meets their needs.

But to sell this to its people—who, like others around the world, are increasingly aware of the importance of privacy—China has had to cleverly redefine that concept, moving from an individualistic understanding to a collectivist one…

Consider recent Chinese legislation like the Personal Information Protection Law (in effect since November 2021) and the Data Security Law (since September 2021), under which private companies face harsh penalties for allowing security breaches or failing to get user consent for data collection. State actors, however, largely get a pass under these laws.

As tends to be the case with these kinds of programs, the digital ID is being marketed as optional — at least during the pilot phase. Chinese residents, the government insists, can “voluntarily” sign up to the program by matching their existing national ID card to facial biometrics. They will then be able to use the digital ID to sign up for and log in to popular apps such as WeChat and Taobao. Whether Beijing actually honours this pledge, to keep its digital identity program optional, time will tell; India’s government certainly didn’t.

Beijing is touting the digital ID scheme as the ultimate form of data protection, notes CPO magazine, “preventing even ISPs and other private interests that might be ‘leaky’ from holding potentially damaging sensitive personal information on the country’s residents.” But the data will not be protected from the prying eyes of the Chinese Communist Party. Critics fear that the real objective is “to further clamp down on expression and the free exchange of information online, eventually removing a means for people to post anonymously or without having their entire internet presence readily open to government inspection.”

Amplifying These Fears

These fears are being amplified by establishment media outlets in the US and the UK. While much of their criticism of digital identity is justified, it is only being levelled at China’s proposed system. Meanwhile, the same media outlets are studiously ignoring the similar systems being developed and rolled out across the West despite the fact that said systems pose arguably an even graver a threat to privacy, freedom of expression and other basic rights (or privileges, as George Carlin called them), since many of those rights are actually enshrined in law.

In the subheading to its article, “China’s New Plan for Tracking People Online“, The Economist asks whether the digital ID proposal is “meant to protect consumers or the Communist Party”. Presumably, it’s a rhetorical question! The FT reports that “China’s powerful data watchdog has proposed tighter controls over users’ online information, including a nationwide rollout of digital IDs, in a move that (has) met sharp pushback from leading technology experts”:

(T)he proposal could drastically extend authorities’ oversight over online behaviour, potentially covering everything from internet shopping history to travel itineraries.

Tom Nunlist, associate director at China-focused consultancy Trivium, said the proposals could “significantly expand the government’s ability to monitor people’s activity online. It would give the police much greater insight into what people are doing online.”

Under existing rules, internet users in China must use their personal ID or phone number to register on platforms such as WeChat and microblogging site Weibo. This allows platforms and authorities to police online activity, such as combating cyberbullying and misinformation, as well as to censor critical discussion of the government.

Nunlist said relying on personal IDs had empowered platform companies to gather user data that could be used for their financial gain. Replacing personal IDs with anonymous digital ones would allow the state to monitor online activity while limiting companies’ ability to track consumer behaviour.

The New York Times helpfully informs its readers that, with or without a Digital ID system, it is already hard to be anonymous online in China:

Websites and apps must verify users with their phone numbers, which are tied to personal identification numbers that all adults are assigned…

The Chinese government has for years exercised tight control over information, and it closely monitors people’s behavior on the internet. Over the last few years, China’s biggest social media platforms, like the microblogging site Weibo, the lifestyle app Xiaohongshu and the short video app Douyin, have started to display users’ locations in their posts.

But until now, that control has been fragmented as censors have had to track people across different online platforms. A national internet ID could centralize it.

With that centralisation of data comes a heightened risk not only of government overreach but also data breaches. Like most governments, China has a chequered history of keeping the personal data it holds secure. For example, in 2022 a hacker stole 23 terabytes of records that included millions of national IDs and phone numbers in a breach of the Shanghai National Police (SHGA). Of course, this pales in comparison with the recent hack of the US-based company National Public Data, which reportedly resulted in the theft of personal records of a staggering 2.9 billion people, including allegedly their social security numbers.

One point that is not mentioned in any of the Western media articles I have read on China’s emerging digital identity system is the enabling role it is likely to play in the eventual roll out of the digital yuan, China’s long-planned, close-to-fruition central bank digital currency. By all metrics, China is closer than any other G-20 economy to launching a full-fledged CBDC, though fellow BRICS economies India, Russia and Brazil are not far behind.

The digital yuan pilot program the People’s Bank of China launched in 2019 now extends to 27 cities. But without a full-fledged digital identity system, it will be all but impossible for China to fully launch its digital yuan. In 2021, the FT wrote: “What CBDC research and experimentation appears to be showing is that it will be nigh on impossible to issue such currencies outside of a comprehensive national digital ID management system.” A 2023 op-ed in Forbes by David Birch, a commentator on digital financial services, described national digital ID as a “foundation for CBDC.”

The fact that China is rolling out a digital identity system as quickly as possible would suggest that a full national roll out of the digital yuan could also soon be in the offing. The fact that none of this is mentioned in any of the Western media articles is perhaps not a surprise given that just about every central bank on planet Earth is planning to do the same as the People’s Bank of China — i.e., launch a CBDC — and CBDCs are not nearly as enticing a prospect to the broader general public as they are to central bankers and government ministers.

A Stark Contrast

The sheer volume of critical coverage of China’s proposed digital ID system in Western media stands in stark contrast to the near-total absence of critical coverage of the digital ID systems being developed by Western governments.

In recent months both the EU and Australia have passed legislation making digital identity a legal reality. How many articles did the New York Times dedicate to either of these developments? As far as I can tell, based on a quick search of its website’s archives, none. Nada. Rien. How about the FT? Again, none. Same goes for The Economist and Time. In fact, it seems that the only time Western news outlets deign to cast a critical look at digital identity systems is when it is in relation to non-Western countries, in particular China and India.

By contrast, the launch of the EU’s e-ID system has been met with a wall of silence by the mainstream press. Nor has there been any coverage of the close cooperation between the EU and the US to align their digital identity standards, even though the US doesn’t even have an official digital ID system in place. This convenient silence, while perhaps unsurprising, is nonetheless unsettling given the potential digital identity has to transform, for better or worse (my money’s on the latter), just about every aspect of our lives.

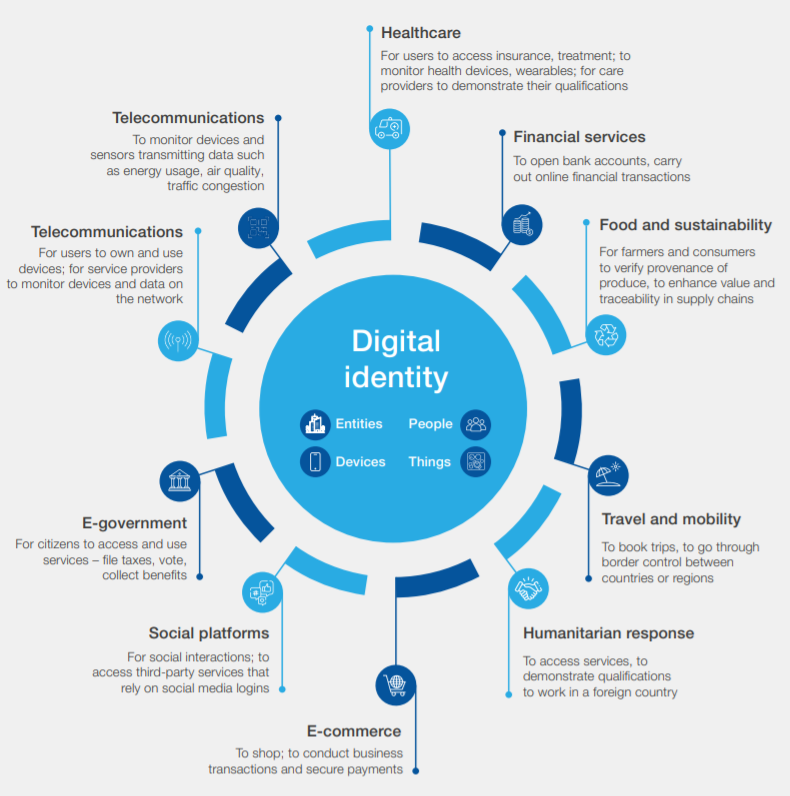

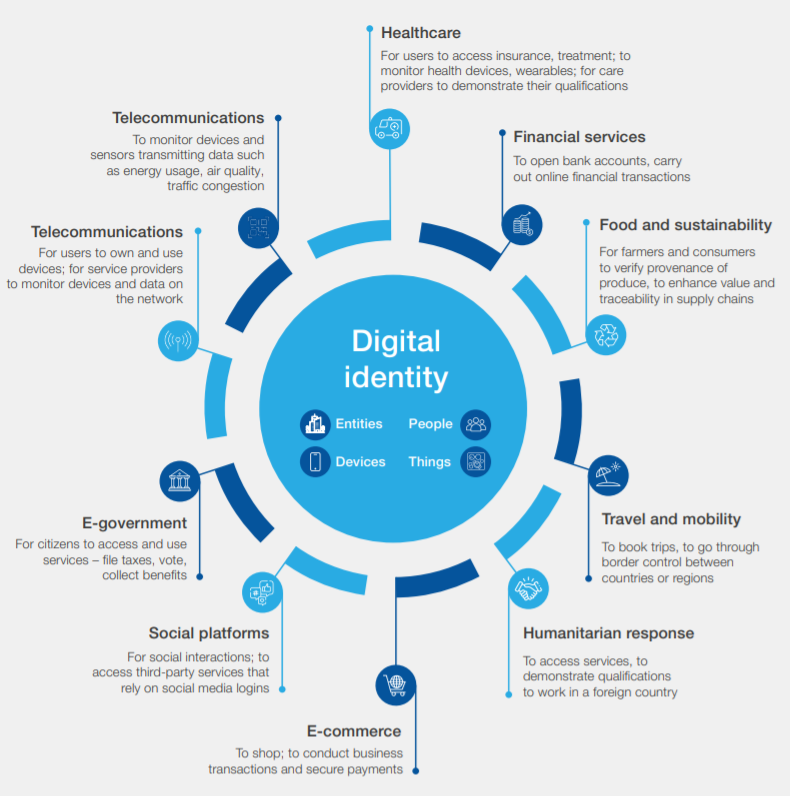

As the World Economic Forum’s now-notorious digital ID infographic (see below) shows, a full-fledged digital identity system, as currently conceived, could end up touching just about every facet of our lives, from our health (including the vaccines we are supposed to receive) to our money (particularly once central bank digital currencies are rolled out), to our business activities, our private and public communications, the information we are able to access, our dealings with government, the food we eat and the goods we buy.

A system like this will offer governments and the companies they partner with unprecedented levels of surveillance and control. And most of the decision processes will be automated.

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who wields a significant amount of backroom influence over the new Kier Starmer government, has described the roll out of digital identity and other digital public infrastructure (DPI) as both “revolutionary” and the “single most important thing that’s happening in the world today, of a real world nature that’s going to change everything”. He also called for everyone to be given a unique online identifier.

Here is Blair sending a clear message to the Starmer government on the eve of its recent electoral victory:

Tony Blair’s advice to Labour on the “single biggest thing that will change everything”.

Rarely do they talk about rights: choice, privacy, free speech when talking about this revolution.@BigBrotherWatch’s work is going to be absolutely critical…

— Silkie Carlo (@silkiecarlo) July 6, 2024

The Starmer government appears to have got at least part of the memo. One of its first acts was to introduce a new digital identity verification services bill. The only mainstream media outlet to cover the story was The Times. According to that article, ministers have promised that people will be able to prove their identity for everything from paying tax to opening a bank account using a government-backed “digital ID,” but they will not be forced to.

London, like Beijing, Brussels and Canberra, insists it will never make digital ID mandatory for people. But India’s Aadhaar system, the world’s largest biometric digital ID system, was also introduced as a voluntary way of improving welfare service delivery. But the Modi government rapidly expanded its scope by making it mandatory for welfare programs and state benefits. It then gradually become all but necessary to access a plethora of private sector services, including medical records, bank accounts and pension payments.

Put simply, life in India without Aadhaar is one of near-total exclusion. As even the Financial Times reported in 2021, “India’s all-encompassing ID system holds warnings for the rest of world.”

As such, all of these government claims that digital ID will be merely an optional extra should be taken with (in the immortal words of Al Pacino’s character in Donnie Brasco, Lefty Ruggiero) a generous “punch of salt”. As we reported in April, the Greek government has already made access to sports stadiums contingent on possession of the digital ID wallet. In other words, if you don’t have download the app onto your mobile phone, you can no longer watch your favourite sports team live and direct.

Making digital ID mandatory for entrance into stadiums is seen as a way of “expanding” the application’s use, Ekathimerini reported at the time. Of course, the policy directly contradicts the EU Commission’s repeated assurances that the digital identity wallet is purely optional and that EU citizens will not face discrimination for not using one, but the EU does not appear to have made any formal complaints.

Was any of this story covered by any of the US or British news outlets now warning about China’s proposed digital identity? Of course not.

One possible silver lining is that in some countries, many, if not most, members of the public appear to be innately distrustful of digital identity.

In the UK, the Open Identity Exchange — a business association that describes itself as “a community for all those involved in the ID sector to connect and collaborate” and whose executive members include Mastercard, IAG, Barclays and Natwest — admit that the UK population’s general fear of government overreach and surveillance makes it harder to develop digital ID ecosystems. In Australia, public trust in digital governance is also low following the publication last year of the findings of the Robodebt royal commission.

From the University of Melbourne’s Pursuit content site:

The so-called Robodebt scheme was touted to save billions of dollars by using automation and algorithms to identify welfare fraud and overpayments.

But in the end, it serves as a salient lesson in the dangers of replacing human oversight and judgement with automated decision-making.

It reminds us that the basic method was not merely flawed but illegal; it was premised on the false belief of treating welfare recipients as cheats (rather than as society’s most vulnerable); and it lacked both transparency and oversight.

At the heart of the Robodebt scheme was an algorithm that cross-referenced fortnightly Centrelink payment data with annual income data provided by the Australian Tax Office (ATO). And the idea was to attempt to determine whether Centrelink payment recipients had received more payments than they should have in any given fortnight.

The result was automatic debt notices issued to people that the algorithm deemed had been overpaid by Centrelink.

As anyone who has ever worked a casual job will know, averaging a year’s worth of earnings across each fortnight is no way to accurately calculate fortnightly pay. It was this flaw that led the Federal Court to declare in 2019 that debt notices issued under the scheme were not valid.

As I have written in previous articles, digital identity programs and central bank digital currencies are among the most important questions today’s societies could possibly grapple with since they threaten to transform our lives beyond recognition, granting governments and their corporate partners much more granular control over our lives. Given what is at stake, they should be under discussion in every parliament of every land, and every dinner table in every country in the world.

The fact they aren’t speaks volumes not only about whose interests these digital identity systems are intended to serve but also about the dreadful job our so-called “Fourth Estate” is doing of keeping their readers abreast of these developments. And that, I suspect, is not an accident. After all, if an open, informed debate on the pros and cons of the biometric identity and surveillance systems being installed around the world — and not just in China — was actually allowed, the public would overwhelmingly reject them. Which is why these systems are encroaching into our lives under the radar, with little public knowledge or debate.