in Recent PostsLast time, I took what could be called an “elitist” view on monetary policy: policy decisions should be made by experts in the field. Today, I’ll take what could be called an anti-elitist view: central banks should seek the views of a range of monetary economists, including those with unorthodox views. Am I contradicting myself? Not at all.

This is Financial Timesin a sardonic opinion piece:

Since 1997, members of the Institute of Economic Affairs’ Shadow Monetary Policy Committee have met once a quarter somewhere on Tufton Street in Westminster, cosplaying as their favourite Bank of England interest rate setters. No one knows exactly why they’re having so much trouble, just as scientists are still puzzled by the mysteries of bird migration.

Still, SMPC meetings follow a familiar pattern: after reviewing the state of the global economy, members discuss the outlook for UK inflation and growth, then debate the appropriate level of borrowing costs. Votes are counted, policy rates are recommended, and the world keeps on turning.

Its diverse membership includes former Invesco chief economist John Greenwood (who believes “interest rates are irrelevant”), Capital Economics non-executive director Roger Bootle (who believes “interest rates are fundamental”) and a few committed monetarists. (Louie, ever the cynic, thinks the SMPC exists purely “to compliment each other every decade when M4 and the inflation charts line up nicely”.)

The SMPC is heavily male-biased – all 14 members are male and pro-Welsh – four of them, including “Brexit economist” Professor Patrick Minford, are based at Cardiff Business School, Juan Castañeda and Tim Congdon both divide their time between the Institute for International Monetary Affairs and the University of Buckingham, and Lirico co-chairs with Professor Trevor Williams of the University of Derby and TW Consultancy, when not moonlighting at consultancy Europe Economics.

Apparently the author thinks it’s laughable that these people have the audacity to give monetary policy advice to the infallible experts at the Bank of England.

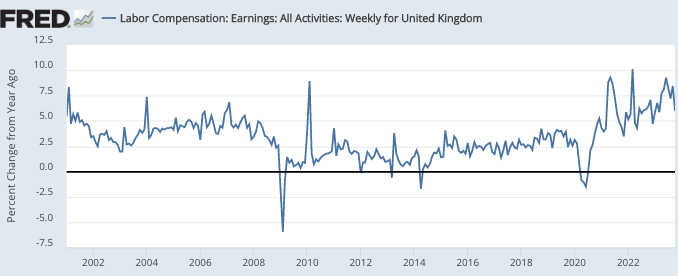

If you want to make a cynical response, you might point to the UK inflation rate for the past three years: If the price hikes are due to a supply shock such as the war in Ukraine, then look at a variable more closely related to demand conditions: wage inflation.

That doesn’t seem like sound monetary policy. Clearly monetary policy was too tight in 2008 and too loose in 2021. I don’t always agree with Tim Congdon, but my recollection is that he criticized both. in real time.

In contrast to F.T. economist We recognise the value of having diverse voices when formulating policy.

In the 2000s, researchers conducted experiments with economics students at the London School of Economics, Princeton University, and the University of California. The experiments used a simple economic model run on a computer that was subjected to random shocks. The students responded by changing interest rates and were graded on how well they managed to keep unemployment at 5% and inflation at 2% over 20 quarters. In every case, committees performed better than individuals. Indeed, much empirical research suggests that well-run committees moderate extreme views, eliminate misjudgments, and are better insulated from political and personal pressures.

I suggested (Chapter 5) Expand the FOMC membership from 12 to 8.2 billion (potentially). Anyone can bet that NGDP will rise by less than 3% or more than 5%, and the Fed will take the opposing bet.