Protectionism Protectionism is currently fashionable, attracting support from both the left and the right. This is not the first time. Protectionism waxes and wanes in popularity, but it’s always been there. Each resurgence has been driven by variations on the same arguments, specifically the infant industry argument.

The argument is simple: protectionism through tariffs and subsidies helps new industries grow by shielding them from foreign competition until they can compete on their own, ultimately leading to greater economic growth than would otherwise be the case. Recently summarized“It wasn’t the free market that transformed America from a colonial outpost into a global industrial power. Free TradeIt was about aggressively protecting our domestic market.”

The problem is that every time the economy recovers, the answer is the same: the increase in domestic output from protected industries was not worth the loss in consumer welfare. In fact, nothing Cass says is inconsistent with American economic history.

First, I would like to comment on the last part of Cass’s comment, “actively protecting domestic markets.” By definition, protectionism is Should Output increases in protected industries appear to be small in magnitude, as seen in frequently cited case studies such as the steel industry in American economic history. cute smallThat’s less than protectionists had promised when they first pushed for the tariffs. One reason is that the tariffs Prices of some inputs (e.g. capital inputs) may also risewhich reduces future productivity growth. So while there may have been a temporary surge in production, that trend was ultimately slowed by the tariffs.

On the cost side, it is important to realize that tariffs, by raising the price of certain inputs, also raise costs for industries that depend on those inputs. This is especially harmful to industries caught up in fierce international competition for export markets. Economic historian Douglas Irwin has noted how this effect was crucial for post-Civil War America: It was effectively a 10% export tax.All of this does not take into account the costs to consumers. Going back to the steel protection case (one of the most cited historical cases), It was found that consumers were suffering significant disadvantages.In other words, “active defense” was a bad thing.

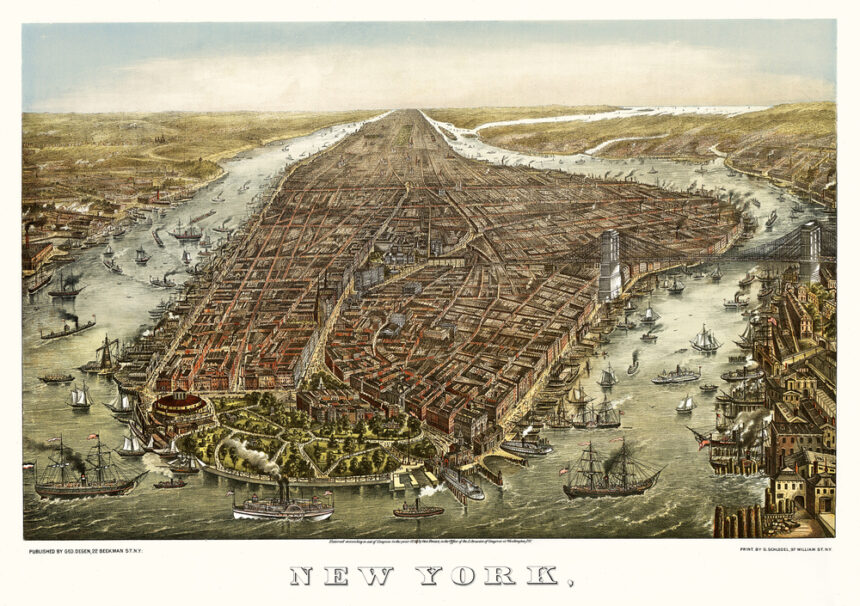

But the first part of Cass’ comment is even more wrong. America was far from being a “frontier” by the 18th century. Economic historians such as Geoffrey Williamson and Peter Lindert have argued that by 1774, The average American colonist enjoyed a significantly higher income than the average Englishman.This is consistent with the large number of immigrants who have immigrated to the United States. My research further shows that the United States has at least At the time, it was 30% richer than the next richest region in the Americas.French settlers in Quebec. Notably, this period before 1774 was essentially a “The most free.” The trade era in American economic history. After the Conquest of Canada, from 1760 to 1775, the North Atlantic functioned as a free trade area that included the United States, Canada, and Great Britain. Most protectionist legislation (such as the Navigation Acts) was either too small to be important or was widely ignored.

To make his case, Cass commits a common sin in economic history: focusing on growth in periods like 1790-1860 or 1865-1913 without taking into account the broader context. What these periods have in common is that they came immediately after highly destructive wars. The American War of Independence, for example, reduced incomes by about 20% through destruction, erasing America’s economic advantage over Britain. Similarly, the American Civil War had a devastating effect on the economy. While both postwar periods did indeed see impressive growth, this was primarily “catch-up” growth, that is, growth that accelerated economic recovery as the country rebuilt after the chaos of the war. Cass and other protectionists often focus exclusively on periods of protectionism and attribute all of the observed growth to the policies they supported. Like a magician’s trick, this tactic is designed to dazzle an audience while concealing the factors that were actually at work.

The case that tariffs are an engine of economic growth has always been weak, and no amount of rebranding every few decades can change its fundamental flaws.

(Editor’s note: Readers may also wish to read Geloso’s Liberty Matters Forum contribution, “Did the American colonies pay too high a price?(See Online Library of Liberty.)

Vincent Geloso is an assistant professor of economics at George Mason University.