Hi, Lambert. Since our readers are geographically dispersed, if you have anecdotal data that supports the themes of this article, please share it with us. (The map is like this in the original article.)

Authors: Gyeong Kim, assistant professor at UC Santa Cruz; Cassandra Merritt, doctoral candidate at UC Davis; and Giovanni Peri, C. Brian Cameron Professor of Economics and director of the Center for Global Migration at UC Davis. Originally published on VoxEU.

The evolution and changing nature of jobs is a feature of developed economies. For example, jobs that did not exist in the United States before 2000 now employ millions of people. In this column, we analyze the role of regional factors and the impact of global shocks in creating “new jobs.”

The evolution and changing nature of jobs characterize developed economies. The most advertised jobs in 1990 did not exist as job titles in the 1950s (Atalayt et al. 2020). Additionally, 63% of jobs in 2018 were jobs that did not exist in the 1940s (Autor, Chin, Salomons, & Seegmiller, 2024). The ability of an economy to create tasks and functions that lead to distinctly new types of jobs (“new jobs”) is critical to job retention and continued economic prosperity (Autor, 2015). Jobs such as “life care planner,” “sommelier,” and “barista,” as well as “data warehouse architect,” “internet marketer,” and “global supply chain director,” did not exist in the United States before 2000 but now employ millions of people.

Recent literature formalizes the idea of changing job content in two main approaches. Studies following the pioneering work of Autor et al. (2003) and Autor et al. (2008) consider employment transitions between occupations characterized by different task or skill intensity. These studies suggest that jobs are shifting from more routine tasks to more non-routine cognitive, interpersonal, and analytical tasks. However, these studies do not mainly abstract from changes in job definitions that capture more detailed job content. A second stream of literature analyzes the role of technology in simultaneously displacing a set of jobs and creating new job opportunities, with the intensity of these two phenomena determining the level of employment growth in the long run (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2019). However, this literature does not systematically analyze the role that exposure to local factors and global shocks (except technology) play in generating “new jobs”.

In a recent paper (Kim et al. 2024), we introduce a new measure of “new jobs” based on introducing new content into job titles and answer the following questions: Is it correlated with specific tasks, skills, and worker characteristics? Are “new jobs” associated with employment growth? And what regional factors and exposure to global shocks predict “new jobs”? These are key questions for understanding the recent evolution and future trends of the US labor market.

Measure new tasks as new content within the job role

Our innovative methodology contributes to the study of changing jobs by identifying “new jobs” through semantic differentiation derived from natural language processing techniques. In doing so, we build on the pioneering concept of “new jobs” introduced by Lin (2011) , which leverages additions to the census job title catalogue, and extend the application of semantic differentiation to detect “new jobs” first innovated by Kim (2024) .

The core of our algorithm is text analysis that converts job titles into high-dimensional vectors to compare their semantic similarity. The vectors assigned by the “Continuous Bag of Words” algorithm are based on the probability that words in a job title appear in a similar context to words in another job title, based on millions of training documents. “New” in this context means “semantically far enough away” from any jobs present in the previous list. After additional technical steps that build on the notion of “sufficient distance” in the quality of the source documents, our approach can be applied to identify “new jobs” using a complete list that represents the set of jobs and occupations in any economy over time. We apply this approach to identify “new jobs” in each of 350 US occupation codes for the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s.

New job characteristics and geography

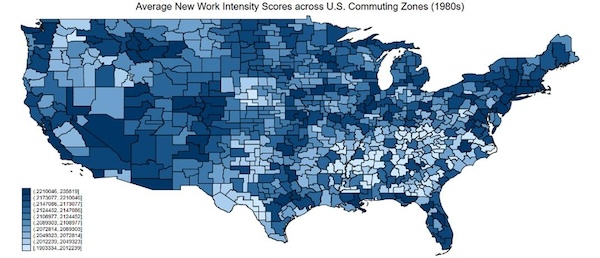

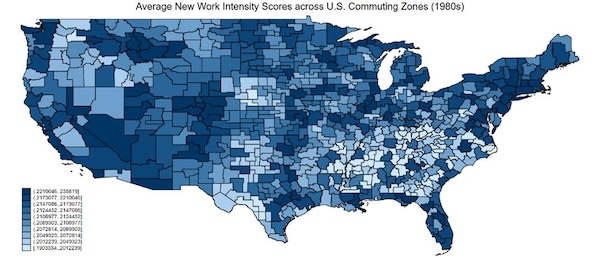

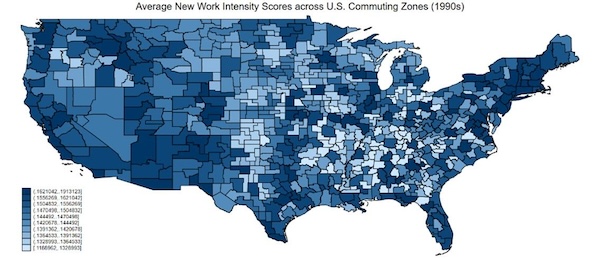

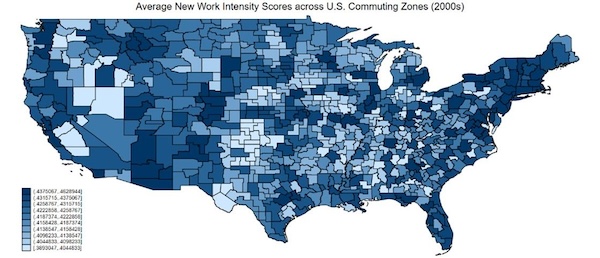

Our first findings situate “new jobs” across occupations and regions. Across occupations, we find that “new jobs” are strongly positively correlated with years of education and intensity of non-routine cognitive analysis and manual interpersonal tasks. We then transform our metric to capture its intensity across the entire US commuting belt based on the regional occupational distribution in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Figure 1 maps the intensity of “new jobs” across decades in the US, highlighting two characteristics:

- Remarkable persistence in the geographic distribution of “new jobs” over decades (e.g., coastal versus southern states)

- Urban areas will create the most new jobs (including non-coastal cities like Denver, Austin, and Chicago)

Across occupations, “new jobs” are significantly and positively correlated with employment growth, and this correlation extends across regions, suggesting a multiplier effect of “new jobs.”

Figure 1 The geography of “new jobs”

Panel A: 1980s

Panel B: 1990s

Panel C: 2000s

Note: The darker the color, the higher the intensity of “new jobs” within commuting distance.

Global shocks and the role of regional factors

We then turn to an analysis projecting “new jobs” in commuter areas from 1980 to 2010. We focus on two economic considerations.

- Regions’ exposure to global shocks: trade competition, new technologies (computerization and robotics), immigration, and the aging of the region’s population

- Strength of regional factors (fixed since 1980): population density, share of college-educated people, share of manufacturing employment, and industrial diversity

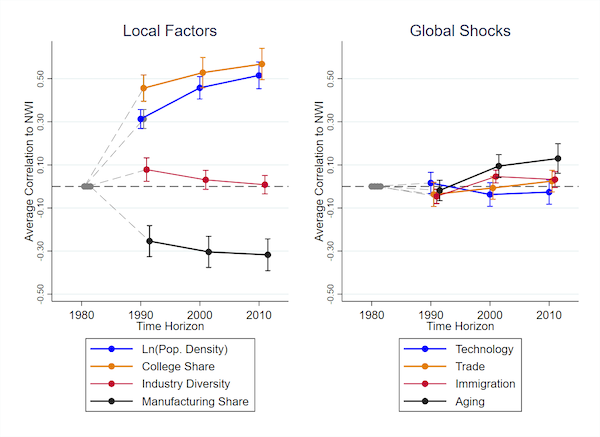

Three key findings emerge: First, a region’s share of the college-educated population in the initial period is the most statistically significant and economically important positive predictor of “new jobs” (Figure 2, left). The next most important predictors are high population density and a low share of manufacturing employment.

Second, exposure to global shocks has a weaker predictive power for “new jobs” compared to local factors (Figure 2, right). Population ageing is the only shock that has a strong association with “new jobs” on average. Further analysis shows that this is driven in particular by the projected share of retirees, suggesting that this group plays an important role in stimulating demand for new services. However, exposure to other global shocks does not show a significant correlation with “new jobs” on average.

Third, the importance of some global shocks becomes clear when considering heterogeneity across occupation types and locations. Exposure to technology has a positive predictive power for the intensity of “new jobs” that specifically originates from occupations with a high intensity of non-routine cognitive-analytical tasks. This type of “new jobs” is also highly correlated with local human capital and population density. Moreover, exposure to trade shocks predicts “new jobs” especially in places with high population density and a large share of the university-educated population, so-called “high-skill cities”. Outside these “high-skill cities”, highly educated immigrants are associated with more “new jobs”, suggesting that they are an important substitute source of human capital related to “new jobs” in places with a low supply of human capital.

Figure 2 How regional factors and exposure to global shocks predict “new jobs”

NoteThe figure shows the increase or decrease in the intensity of “new work” predicted by a one standard deviation change in either the indicated local factors (left) or exposure to global shocks (right) over the period 1980–2010.

The causal role of local universities and human capital supply

The set of predictions emerging from our analysis highlights that local human capital is a potentially important determinant in stimulating “new jobs” and mediating the impact of global shocks on the local labor market’s ability to create “new jobs”. We therefore improve the identification of the causal role of local human capital supply through instrumental variable (IV) estimation. We exploit the historical presence and density of local universities, dating back to the establishment of land-grant universities before 1920, to isolate the supply-side effect of university share in 1980. The IV estimation finds that human capital supply has a statistically and economically significant positive impact on local “new jobs” intensity.

Our findings highlight the essential importance of human capital supply in the creation of “new jobs”. The findings suggest that highly skilled workers have a comparative advantage in performing new jobs. This may be in part because these local institutions are better able to adapt to changes in the demand for skills, which in turn facilitates the implementation and diffusion of “new jobs”.

Conclusions and research directions

Kim et al.’s (2024) innovative measure of “new jobs” deepens our understanding of how labor evolves. The algorithm and approach can be used to identify “new jobs” based on the emergence of semantically distinct occupations in other historical periods and other countries, further extending and generalizing this analysis.

A first analysis of regional and global factors predicting “new jobs” asserts the role of regional human capital as a key factor not only in generating “new jobs” but also in transforming some shocks (such as trade and technological change) into “new jobs” (Gagliardi et al. 2024). Interestingly, the growth of the retired population is associated with an increase in “new jobs”, which seems to be related to the demand for new services.