This week is Naked Capitalism’s fundraising week. We’re pleased to invite 146 donors to join us as they have already invested in our efforts to fight corruption and predation, especially in the financial sector. Donation pageHere’s how to donate by check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Why are we doing this fundraiser?, What we accomplished last yearAnd our current goal is to Strengthening IT infrastructure.

Hi, I’m Lambert. I sometimes throw around the mantra that “the only real market is the labor market.” Maybe that’s true…

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published on Wolf Street.

`

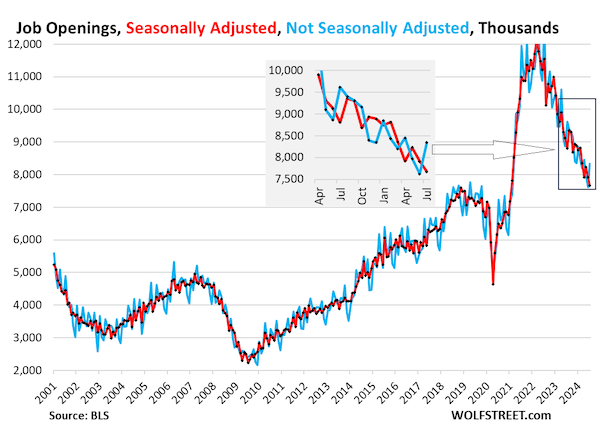

Data released today by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that job openings increased by 720,000 to 8.34 million in July, not seasonally adjusted. Job openings typically surge in July; last year they increased by 750,000, but July 2019 saw an increase of just 250,000, and July 2018 saw an increase of just 414,000. This makes July’s increase significantly larger than the previous two years, pre-pandemic (blue line in chart below).

However, seasonal adjustments to try to smooth out this seasonality caused the seasonally adjusted number of job openings to fall by 668,000 to 7.67 million (red). The inset provides details through April 2023.

Beyond month-to-month seasonality, we see trends. Job openings have declined since the frenzy of labor shortages, but are still well above pre-pandemic levels in data going back to 2001. So are job openings now normalizing? What is normal? We’ll explore these questions shortly.

The data is based on a survey of nearly 21,000 workplaces released by the BLS today as part of the Job Openings and Labor Movement Survey (JOLTS).

What is normal?

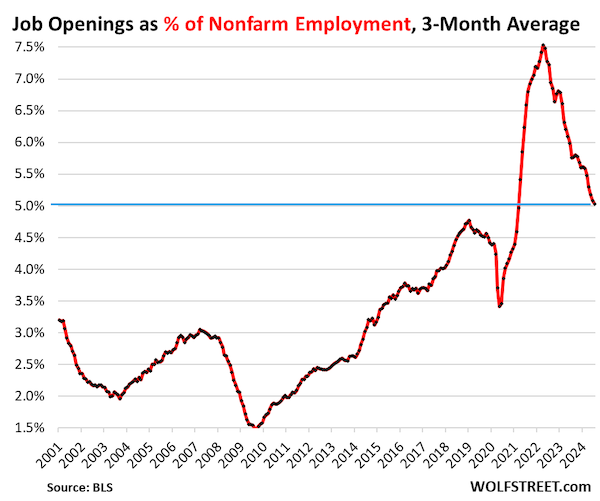

Ratio of job openings to nonfarm payrolls It takes into account job growth over the years. As population, labor force, and employment grow over the years, the number of job openings should grow accordingly. The ratio of job openings to nonfarm payrolls shows this relationship.

On a seasonally adjusted basis, job openings as a share of nonfarm employment fell to 4.9 percent, but are still higher than the peak during the strong labor market in late 2018 and significantly higher than any period since 2001.

The three-month average, which removes month-to-month fluctuations, fell to 5.0%, still well above pre-pandemic levels. This suggests that while the labor shortage has largely disappeared, the labor market remains relatively tight compared to pre-pandemic norms.

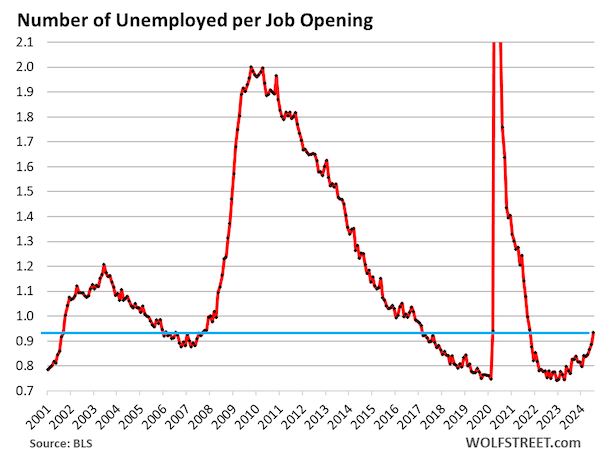

Number of unemployed people per job opening It’s one of several indicators of labor market tightness — the supply of labor relative to jobs — that Powell mentions frequently in his news conferences.

The unemployment figure includes some of the more than 6 million immigrants who came to the U.S. between 2022 and 2024.Congressional Budget Office Data) is considered unemployed because he is looking for work but has not yet found one.

this The large influx of immigrants has led to an increase in the number of unemployed people. However, as we will explain later, layoffs and resignations remain at historically low levels.

The July Employment Report had 7.16 million unemployed people looking for work, while today’s JOLTS data showed 7.67 million job openings in July (both seasonally adjusted). This means that for every job opening, there are 0.93 unemployed people looking for work.

Viewed from this perspective, including the large number of immigrants still looking for work, the labour market is looser (more available labour) than during the relatively tight labour market periods of 2018 and 2019.

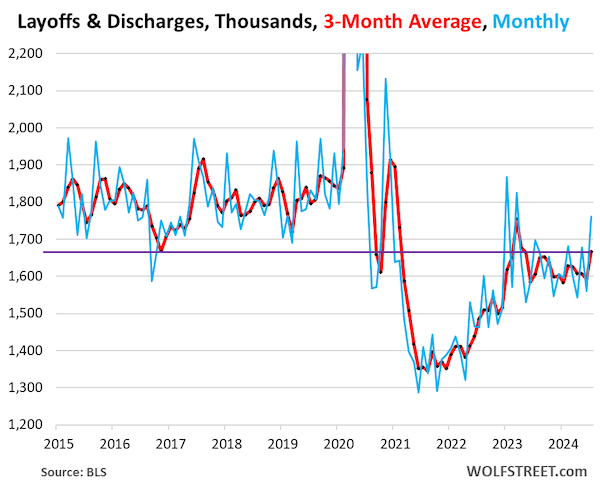

Layoffs and dismissals After a steep decline in June, it jumped to 1.76 million in July. This is very volatile data with big squiggly lines from month to month. The three-month average flattens out some of the squiggly lines. It rose to 1.67 million, but remains in the same range since early 2023 and below pre-pandemic lows.

Initial unemployment claims numbers reported by the Labor Department paint a similar picture: Despite some breathless headlines about layoff announcements around the world, there have been fewer layoffs and firings than there were during the pre-pandemic economic boom.

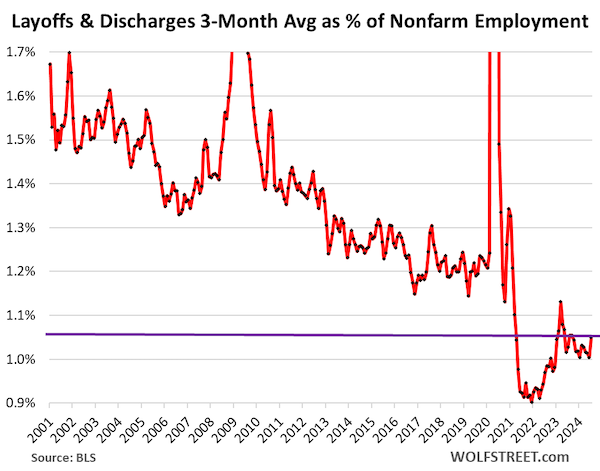

Layoffs and layoffs in nonfarm employment This ratio takes into account employment growth over the years.

From that perspective, layoffs and resignations are still far lower than normal (we use three-month averages of layoffs and resignations to eliminate large month-to-month variations).

This is a sign that employers are sparing workers. Some economists speculate that employers are “hoarding” workers because they suffered labor shortages after making mass layoffs during the pandemic and were unable to rehire those they had let go. If true, that’s a good thing. Employers may have learned something.

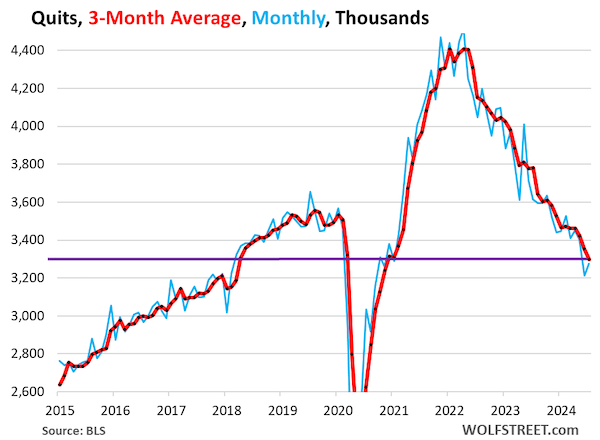

And the workers stopped quitting. The number of people who voluntarily quit their jobs rose to 3.28 million in July. The three-month average fell to 3.3 million, well below the levels of 2018 and 2019.

After mass unrest during the pandemic as workers moved from job to job and industry to industry seeking better wages and working conditions, they appear to have calmed down.

Fewer voluntary resignations and record lows in layoffs and terminations mean fewer job openings to fill, which means less hiring and less competition for labor. The mass turnover during the pandemic is definitely over.

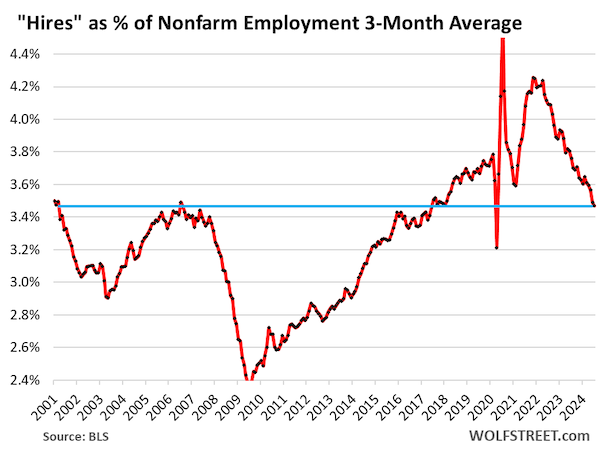

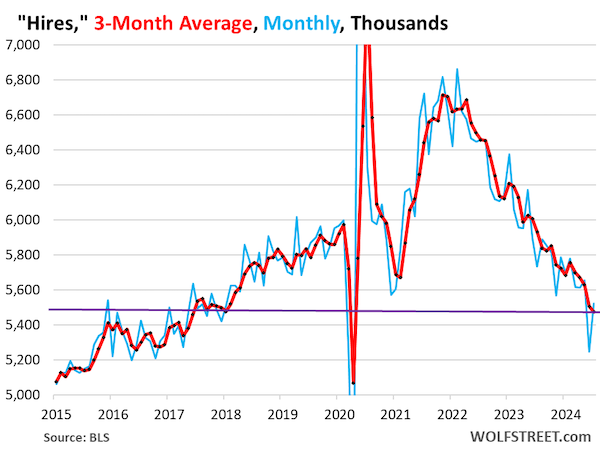

Hiring surges Seasonally adjusted, home sales rose to 5.52 million in July after a decline in June. The three-month average fell slightly to 5.47 million.

Again, fewer voluntary departures and historically low layoffs and terminations mean fewer job openings to fill as employers hang on to their employees, which means less hiring. And that’s part of what we’re seeing here.

The other part we’re looking at here is, The economy is currently creating jobs at a slower pace than in the stronger periods of 2022 and 2023.and there are fewer new jobs to fill.

Relationship between nonfarm payrolls and payrolls While this is below the levels that would have marked a tight labor market in 2018-2019, it is well above nearly every month of the previous period going back to 2001. Is this level of employment as a percentage of payrolls historically “normal”? Probably.